1. Electricity

The first exhibitions

Electricity was an attraction at the great international exhibitions held at the end of the 19th century. New inventions were displayed and were part of the entertainment. The first special exhibition for electricity was held in Paris in 1881. Among the inventions exhibited were dynamos, incandescent lamps, telephones, electric trams and cars.

The Frankfurt Exhibition of 1891 has been called "the start of the age of electricity", and contained a sensation. A successful transmission of high-voltage alternating current from the village of Lauffen to the exhibition grounds in Frankfurt proved that electricity could be transported over long distances. Despite a distance of 175 kilometres, the power loss in the lines was limited. The transfer marked that alternating current was in important respects superior to the competing direct current system.

The Lauffen transfer also caused a stir in Norway. The power from the Norwegian waterfalls, which were far away from cities and towns, could be developed and transferred to where it was needed. Engineers, business people and politicians alike now realized that water power was becoming valuable.

Direct current dynamo

Among the Norwegians who visited the exhibition in Paris in 1881 was a delegation from the Navy's main shipyard in Horten. They bought a Gramme direct current dynamo to power the lighting system of the torpedo boat Od, built at the shipyard in 1882. Gramme competed with Siemens in the race for the electricity market.

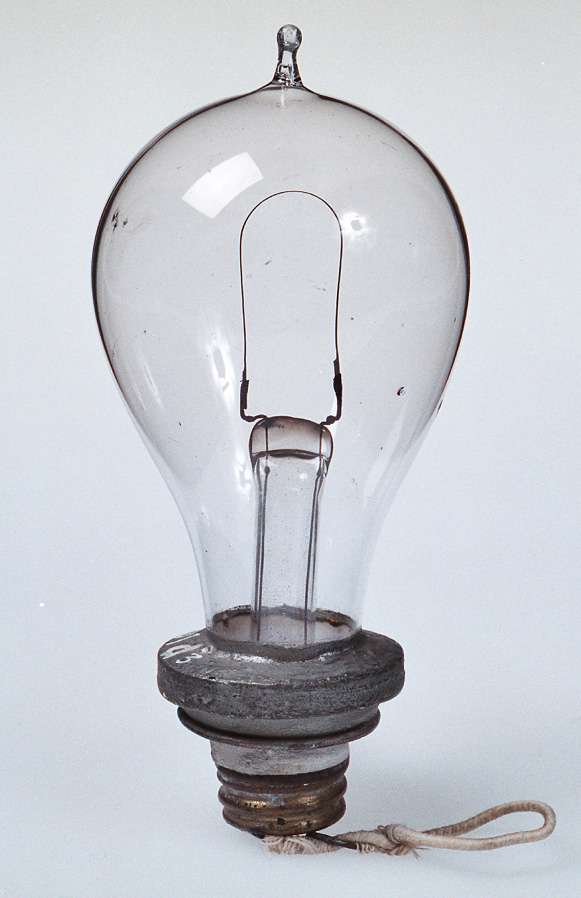

Edison's carbon filament lamp

Swan's charcoal wire lamp

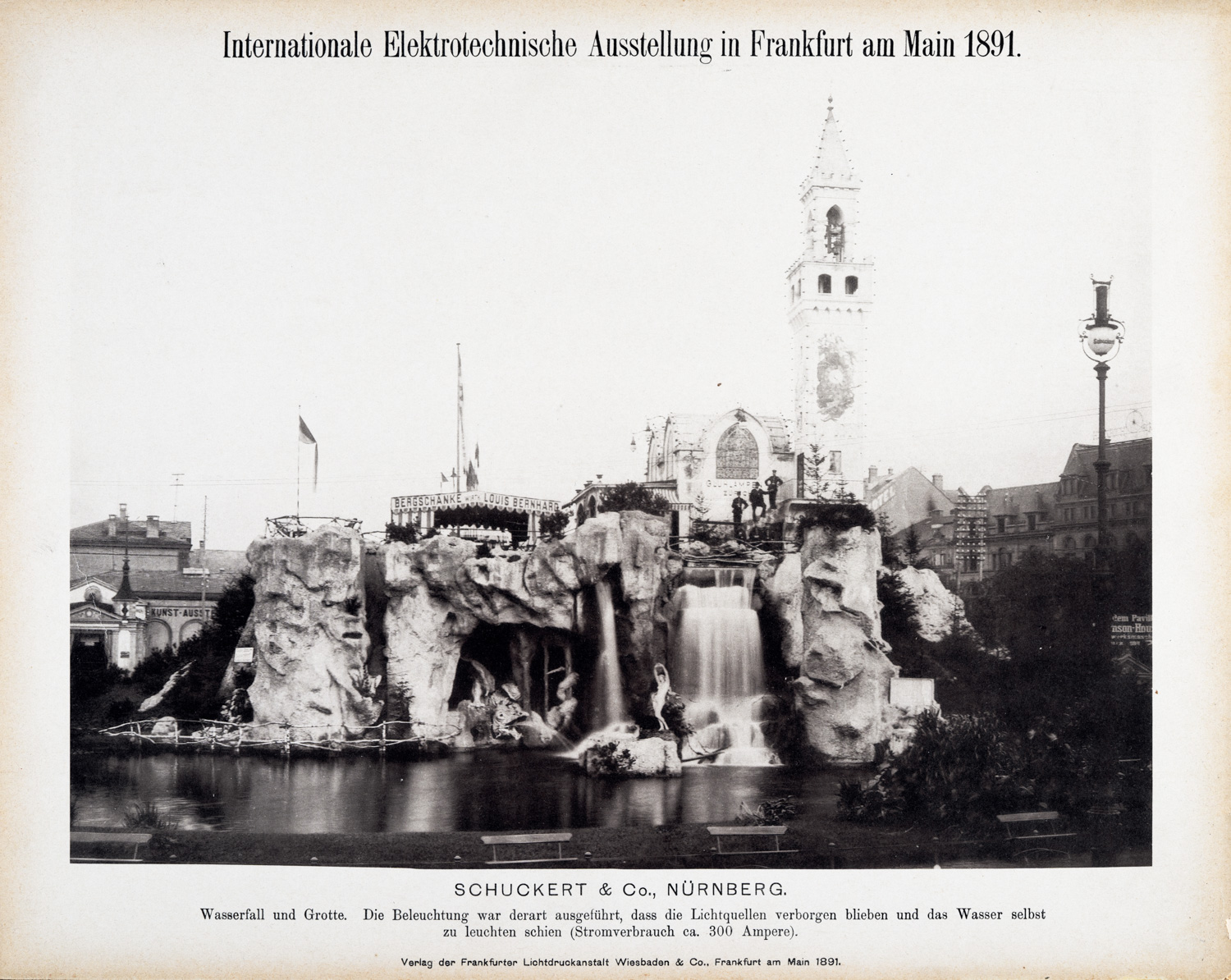

Album from the "Internationale Elektrotechnische Ausstellung in Frankfurt am Main"

The box contains photographs from the electrotechnical exhibition in 1891 with explanatory text about manufacturers, technical innovations and the exhibition itself.

Transmission of alternating current

At the electrotechnical exhibition, high-voltage transmission of three-phase alternating current was introduced for the first time with the transmission of power 175 kilometers between the power plant in Lauffen and the exhibition area in Frankfurt. The installation depicted an artificial waterfall and a grotto and was a spectacular part of the exhibition.

Photo: Unknown/ published by Frankfurter Lichtdruckanstalt, Wiesbaden & Co.

Dynamo, direct current and alternating current

It takes ingenuity to convert energy from one form to another. To transform the power from something that moves, such as running water or wind, into electrical power, you need a generator. A generator can either produce direct current or alternating current. In everyday speech, a generator that produces direct current is called a dynamo. Direct current is electric current that moves in one direction. Alternating current changes direction many times per second. In the early phase, direct current and alternating current competed, but eventually alternating current became the standard for the power grid, partly because it was more efficient to transmit alternating current over long distances.

Dynamos did not exist until the 1830s, and they did not become reliable enough for industrial use until the 1870s. They used powerful magnets and a rotating coil of copper wire to generate electric current. A motor is the opposite of a dynamo – it transforms current into rotary motion.

Direct current dynamo type T

Industry was an early adopter of direct current for electric lighting. The textile factory Nydalens Compagnie had acquired a British Edison-Hopkinson dynamo in 1884. Five years later, the factory used this Swedish Wenström dynamo, manufactured by Frognerkilens Fabrik. Norwegian electrical factories also wanted to participate in the competition for the growing power market together with the major international players.

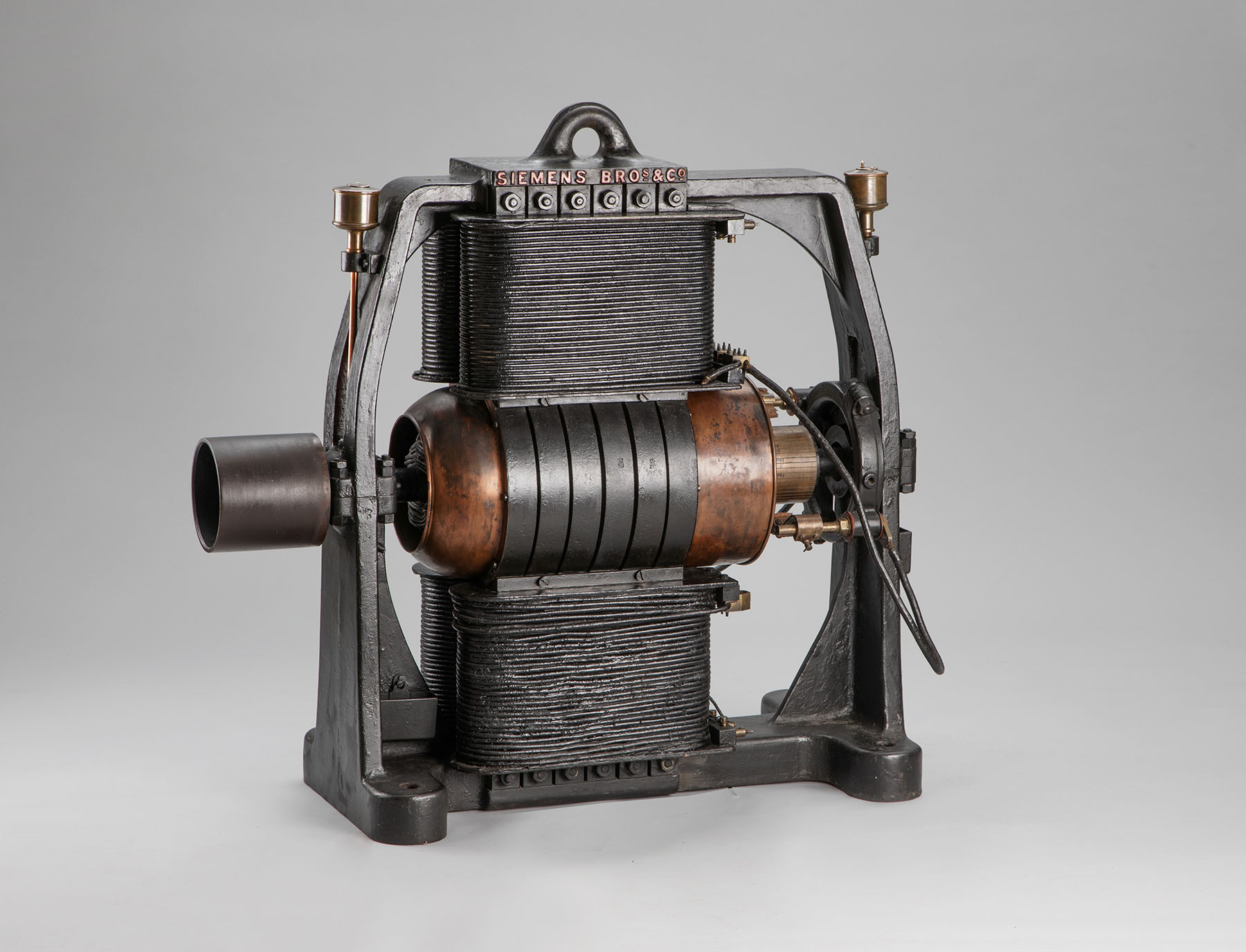

Siemens Brothers DC Dynamo

The wood processing company Laugstol Brug in Skien was the first in Norway to sell surplus power from its own electricity plant to private consumers. Two dynamos purchased in 1885 generated electricity from hydroelectric power that provided light for 120 carbon filament lamps at the company. After a fire that same year, the dynamo was repaired at Frognerkilens Fabrik and sold on to Follum Fabrikker in Hønefoss, who gave it to The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology in 1941.

Direct current motor

An electric motor is the opposite of a dynamo: It converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. This electric motor was used to drive a cooling machine at the Pellerin margarine factory in Oslo around 1900. It was made at Storms Elektriske Verksted in Oslo.

Alternating current motor

Alternating current came into use later than direct current. In the same way as direct current motors, alternating current motors could transform electricity into mechanical energy. The alternating current motors had a wider range of use than the direct current motors, and both types are still used. This was used in a self-playing piano in the 1930s.

Model of Siemens DC dynamo

Industrial leader and engineer Werner Siemens discovered the electrodynamic principle in 1866. He built a self-magnetizing dynamo that converts mechanical energy into electricity. This marked the breakthrough for the practical use of electricity, and it became possible for the first time to produce electricity in a cheap and efficient way. In many countries, electricity was generated from coal, oil, or gas. In Norway, it was early linked to hydropower.

Magnetoelectric rotary machine

In the 1850s, the instrument maker and mechanic Emil Stöhrer from Leipzig improved Faraday's electric motor, which had converted electrical energy into mechanical energy. The machine was in demand as an energy source in small craft businesses. It was also used to demonstrate electricity. The University of Oslo acquired the machine for physics experiments.

Communication

Electricity opened up new forms of communication. Whereas previously it had taken days or weeks to send a letter, the telegraph transmitted messages in seconds. The signals were sent through cables and wires. Eventually, radio telegraphy made it possible to transmit wirelessly through the air. Norway's first telegraph connection came into operation between Oslo and Drammen in 1855. Twenty years later the telephone was launched. In this way, people could also talk to each other over longer distances.

New technology created new jobs. Wires had to be stretched, equipment installed, and people were needed to operate telegraph stations and telephone exchanges. Both the private and the public rooms changed character. Suddenly it was possible to keep in touch with friends and family far away or to quickly confirm an agreement. In Norway, as in the rest of Europe, faster communications revolutionized news delivery. Between 1853 and 1856, for example, newspaper readers were continuously updated about the war that was fought on the Crimean Peninsula by the Black Sea. Never before had it been possible to follow the progress of the war "live".

Indicator telegraph

Telegraph apparatus from 1871 made by the instrument maker Digney Freres & Compagnie in Paris consists of transmitter, receiver and clock. The pointer telegraph works in that the pointer pointing to letters placed on a dial is sent from one place and received in another. The apparatus belonged to the University's physics collection.

Telephone "Tax"

This desk telephone was launched in 1884 and had a fixed microphone and a loose ear tube. The bifurcation was the forerunner of the telephone handset. It was powered by a local battery. The model had several nicknames, including "skelophone", "the Eiffel Tower" or "the sewing machine" because of its shape. The manufacturer was the Stockholm firm LM Ericsson, which made telephones for the Nordic market from 1880 onwards. This phone was used in Stavanger.

Lent by Tanja Bergby.

Volta column

Electrical voltage can be created using cells of metals such as copper and zinc together with basic wetted cardboard or leather. The voltaic column was invented by Alessandro Volta in 1799 and is the forerunner of the battery. The copy was made at the museum in 1937.

Magnetoelectric induction apparatus

This device was built by instrument maker Andersen in Drammen in 1869 for the University's physics collection. The device made it possible to feel electricity. Electrotherapy was used in medicine to treat pain, paralysis and neuroses.

Cable test, the first transatlantic telegraph cable

The first cable was laid between Ireland and New Foundland in 1858. The first telegram was a greeting from the British Queen to the American President. The technology had not yet been fully developed. The signal was weak, and the message took a long time to arrive. After a few weeks the cable had completely stopped working.

Cable trial, the second transatlantic telegraph cable

In 1865 a new submarine cable was laid between Ireland and New Foundland which worked. From now on, telegrams could be sent across the Atlantic. Laying the Atlantic cable was the London firm Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company's first major project.

Cable test, the section Scandinavia Great Britain

The submarine cable between Great Britain and Scandinavia was started in 1868 and ran from Newbiggin-by-the-Sea north of Newcastle in England to Hirtshals in Denmark, Marstrand in Sweden and Arendal in Norway. The cable was manufactured by the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company and laid by the Great Nordic Telegraph Company.

Cable test, high current

The submarine cable between Great Britain and Scandinavia was started in 1868 and ran from Newbiggin-by-the-Sea north of Newcastle in England to Hirtshals in Denmark, Marstrand in Sweden and Arendal in Norway. The cable was manufactured by the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company and laid by the Great Nordic Telegraph Company.

Map of telegraph cables from Europe via Russia to Japan

The Great Nordic Telegraph Company was responsible for laying the cables marked in red. The black cables were laid by other companies.

From the book Det Store Nordiske Telegraf-Selskab 1869–1894, Overview card IIII , 1894.

2. The Concession Acts

Who can own the natural resources?

Those who secure control over natural resources such as land, water, forests or oil often receive many advantages. Having control over a resource, for example a waterfall, means that you have secured something similar to a monopoly. It gives the opportunity to cash in an additional profit, or basic interest as it is called. The value of hydropower increased towards the end of the 19th century thanks to better technology for power transmission. Norwegian speculators and powerful foreign capitalists got rich buying and selling the waterfalls.

In 1906, the Storting was notified that some of the most attractive waterfalls were about to fall into foreign hands. In a hurry, the politicians passed a law which said that all private actors had to apply for permission - a license - for the purchase of larger waterfalls. The state, counties and municipalities did not need a licence. The law was discussed and strengthened several times. Perhaps the most important provision was that completed power plants were to be transferred to the state free of charge after a maximum of 60 years. The principle is known as the right of repatriation.

Statuette in silver

The silver statuette was a gift from the board of Norsk Hydro to director-general Sam Eyde on his 50th birthday in 1916. The lavish statuette can stand as an expression of the great value private players could earn from Norwegian natural resources. At the top, Såheim power station in Rjukan towers over five of Hydro's hydroelectric plants and factories. Produced by the goldsmith company J. Tostrup.

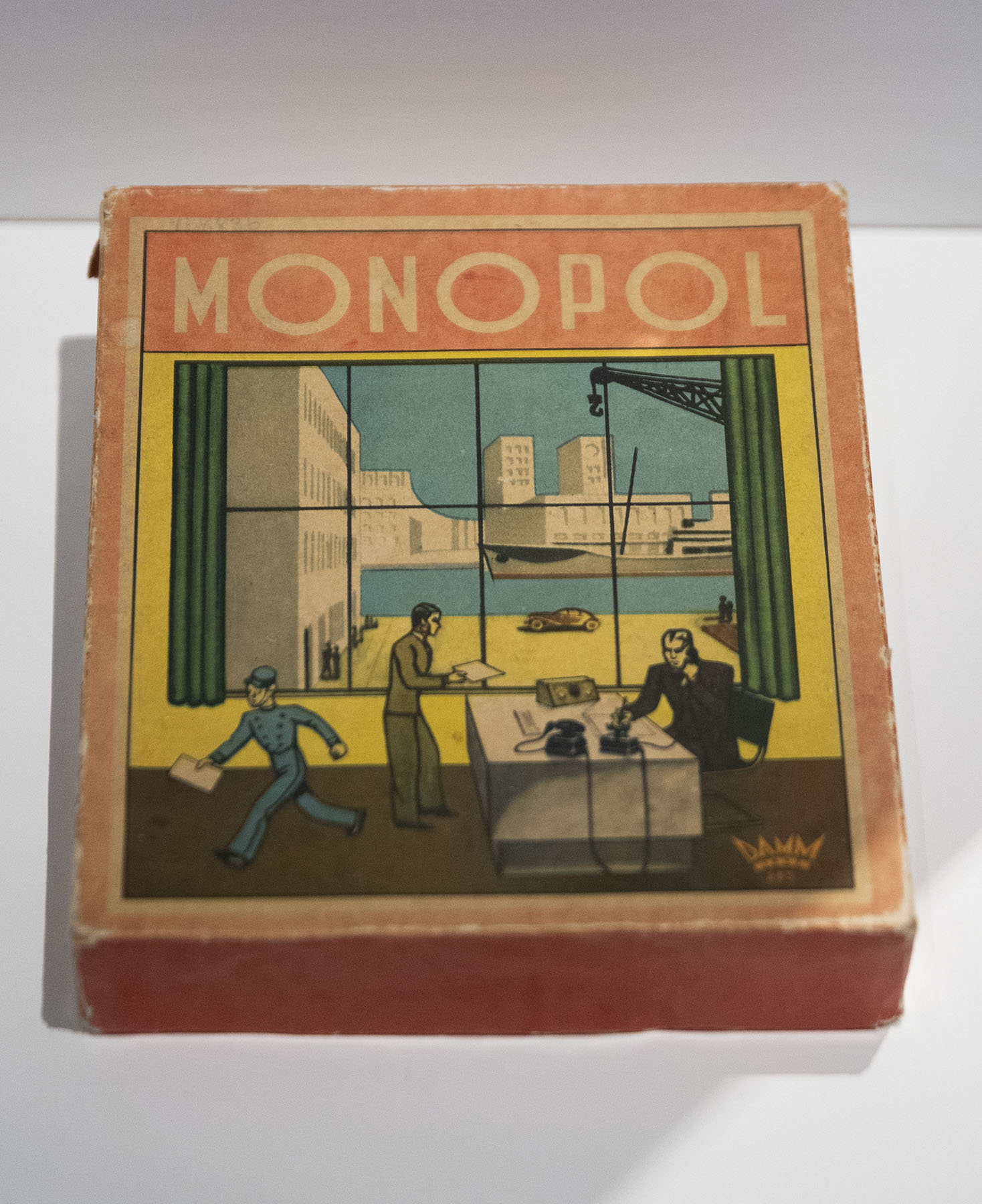

Monopoly game

Insulator

The insulator is an important component in power transmission. The higher the voltage in the line, the more insulator cups must be used. Construction of high-voltage power lines in Norway gained momentum after 1900. This insulator with many bowls was a gift to The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology from importer and engineer Christian Dick in 1929.

Oil concessions

The Concession Act from 1917 is the start of a long tradition of public management of energy resources. In the same way as with hydropower, the idea was that the oil and gas resources at the bottom of the North Sea belonged to the community. The first round of licenses for oil extraction on the Norwegian continental shelf was announced in 1965. The American Phillips Petroleum Company was one of the oil companies that applied for a permit, got it and found oil.

The image is an optical illusion. Some people see the cat right away, others never. Do you see the cat?

Illustration: Unknown

Cigarette case in silver

In January 1906, Norsk Hydro held its first full board meeting. It took place in Paris because the company's main shareholder was the major French bank Paribas. The engraving on the back of the case shows that it was a gift to CEO Sam Eyde from the board of Hydro. It says "In memory of our first board meeting in Paris".

Georgism: Do you see the cat?

Georgism was a social reform movement that gained international traction in the 1890s, named after the American economist Henry George. He is known for his proposal for land rent tax, which is today an important source of income for the Norwegian state. Georgists speak of "seeing the cat." The expression is about opening our eyes to the extent to which ownership of land affects our economy.

The image is an optical illusion. Some people see the cat right away, others never. Do you see the cat?

Illustration: Unknown

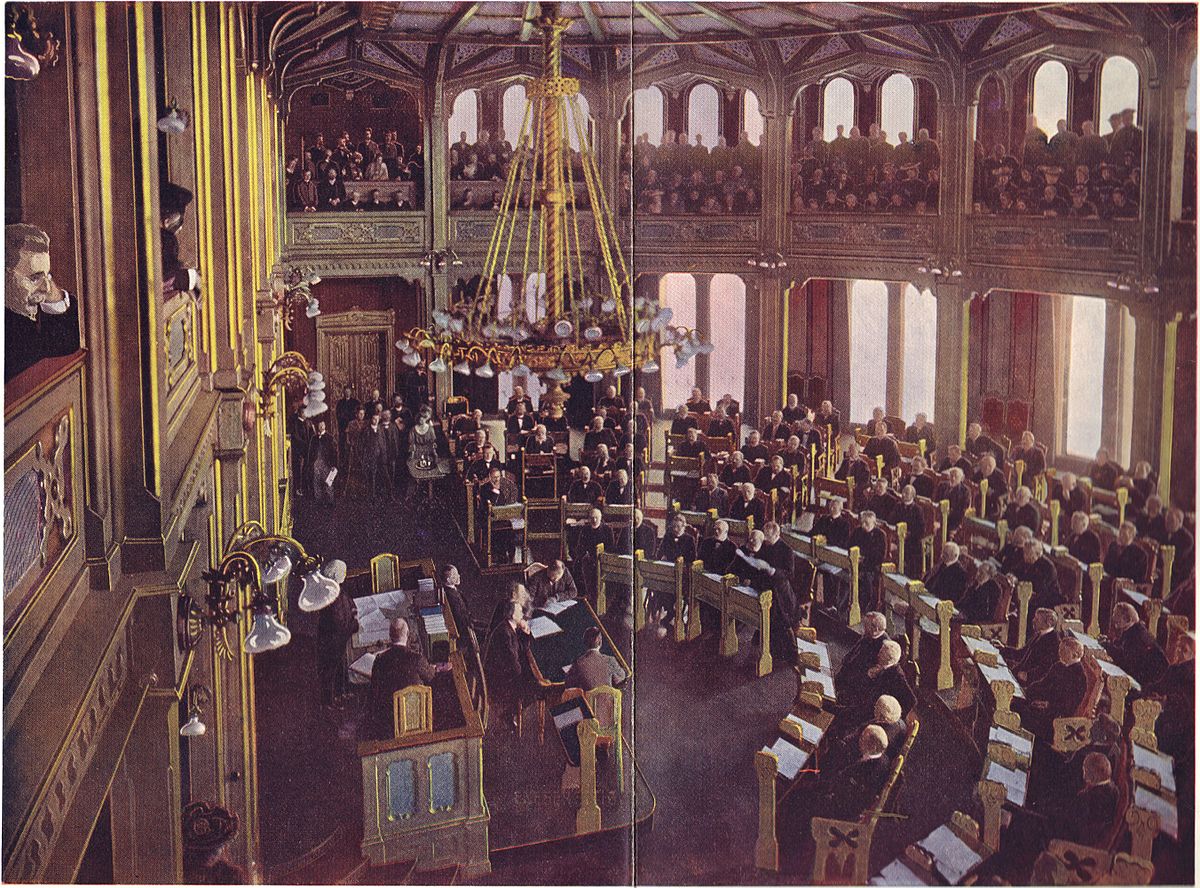

The dispute over the concession laws

Over a period of ten years, from 1906 to 1917, regulation of Norwegian hydropower was hotly debated in the Storting. Business liberal politicians argued that the waterfalls should go to both Norwegian and foreign buyers. The socialists wanted a state monopoly on hydropower. In between stood the majority. They believed that the concession laws should not prohibit, but regulate investments paid for with private capital, whether it was Norwegian or foreign. Photo: Frederik Hilfling-Rasmussen

Sam Eyed

Sam Eyde was an industrial builder and engineer. He helped establish Norsk Hydro, where he was general director from 1905 to 1917. Eyde's investments in hydropower made the Norwegian authorities aware of the need to regulate the purchase and sale of waterfalls.

Photo: AB Wilse/ The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology

Danger, regulation, control

Electricity was a new and dangerous technology that had to be regulated. The politicians adopted laws and regulations which the supervisory authorities subsequently followed up. The power plants were responsible for safe power production. With the help of technical systems, the transmission of electricity was managed from the power source via wires, cables and transformers out to the consumers. Large masts were set up for high-voltage transmission, and with the consumers, cables, switches and fuses were the technical equipment that ensured that the current went where it was supposed to and that it was interrupted if it got out of control.

The development of safe electrical installations was followed up with the establishment of Norway's Electrical Material Control (NEMKO) in 1933. All material that was to be used in the Norwegian power grid had to be approved and bear the NEMKO mark. This statutory arrangement was discontinued when Norway joined the EEA in 1994.

Fuses

The fuses control the current by breaking it in case of overload, short circuit and, in the extreme, fire. The fuse elements have been used at Oslo machinist school around 1900.

Knife breaker

With switches, the power can be turned on and off. This knife switch was first used at Røros Kobberverk, which from 1896 received electric light from Norway's first power station with alternating current, Kuråsfossen. There were big savings for the mining operation by using electric light, and it also improved the working conditions of the miners. After 1901, the switch was used in the wagon hall of Trondheim Sporvei.

Discharge bullet

Lillestrøm's municipal electricity works from 1912 supplied electricity to street lights, business premises and a few private homes. This was used in the plant's control and testing station. After testing the equipment, the voltage had to be removed during discharge. It created a spark and perhaps a bang between the equipment and the bullet.

Coil for surge protection, Drammen electricity plant

Not all cities had easy access to hydroelectricity, as a river with a waterfall ran through the city. When Drammen got electricity in 1903, the power had to be obtained from Gravfoss in Geithus in Modum and transferred to a transformer at Bragernes. From there, the power could be sent out to the customers. In 1932, all households in the city had electricity

Test apparatus

NEMKO was responsible for testing electrical equipment. This apparatus was used to test lamp holders.

Power development

Construction workers at Rånåsfoss power plant climbed a high-voltage mast during assembly. The power plant in Glomma was developed between 1918 and 1922. Up to 1,200 men worked at the plant at the same time, where a separate community with a school, infirmary, post office and telegraph grew up.

Photo: Unknown/ Norsk Teknisk Museum

The image is an optical illusion. Some people see the cat right away, others never. Do you see the cat?

Illustration: Unknown

Administrative control

In 1891, the first law regulating electricity was passed. Before that, the responsibility for checking fire-hazardous installations had rested with the private insurance companies. A separate public supervision of electricity works was established in 1896.

Beyond the 20th century, hydropower gained an increasingly large place in Norwegian energy supply. The state-owned Norwegian Water and Energy Agency (NVE) managed the water and energy resources in the country. Large power plants that were regulated under the concession laws produced most of the power. But most power stations around 1920 were small and privately owned. Landowners were encouraged by the authorities to develop waterfalls for their own use. The electrification of the villages took place in collaboration between the public through laws and administration, private actors such as owners and the electrotechnical industry that produced the equipment.

Meter of currents in water

This hydrological instrument from the 1880s was called a "flügel" and measured speed, water quantity and currents in the watercourse. It was used by the Kanalvesenet, which was responsible for the utilization of Norwegian waterways before the "agency" became part of the newly formed NVE in 1921.

Securing element with two plugs

Olaf O. Rogndal's electrical plant had all the technical equipment necessary to ensure the transmission of electricity from the small power plant he had built to the farm he ran nearby.

Cord with plug for heater

Small power pioneer Olaf O. Rogndal had electricity installed in his house in the years after 1900. Then the family had lights, electric cooking appliances and heaters installed.

Book About the utilization of smaller waterfalls

In 1913, the book was published by Vassdragsvesenet, which was the forerunner of NVE. The aim was to encourage private individuals with their own waterfalls to set up their own small power plants. This was particularly relevant in the villages where the infrastructure for electricity had not yet been developed. The small power plants were exempt from licences.

Poles with power lines at Homme farm

Olaf O. Rogndal built Vest-Telemark's first power station in the 1890s with a turbine, dynamo and electrical equipment that transferred the power from the river to the farm. The current also powered the machines at Rogndal's saw and wood factory.

Cleaning of grass seeds

The call to build private power plants was supported by industry that sold electrical equipment for agricultural machinery and household lighting and heating. NEBB published the booklet Landbruk & electricity in 1914, where the cleaning machine for seeds was presented.

Photo: Severin Worm-Petersen/ The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology

3. City lights

Light in the home

Many tasks in the home need light to be carried out. Kerosene lamps together with tallow candles were the most common light sources in Norwegian homes throughout the 19th century . Eventually, lamps were used which were intended for specialized areas of use. The ceiling lamps provided general illumination of the room, while portable lamps were used for precision work such as reading or sewing.

Electric lighting was less flammable, cleaner and easier to use than candles and kerosene. After the turn of the century, the power companies saw a sharp increase in the number of customers. The major breakthrough for electricity in Norwegian cities and towns came in the years after the First World War. By the end of the 1930s, 80% of households had installed electricity. This was the highest proportion in the world.

Candlestick for grow candles

With five arms, the candelabra lit up dark rooms. The glass prisms further reflected the effect of the flames from the wax candles. Loose figures of birds belonged and could replace the candles. It is made of gilded zinc and stood in a house in Meltzers gate in Oslo.

Lanterne de poche

The flashlight consists of candles and matches with scratches in a metal box. The mirror on the inside of the lid reflected and amplified the light when it was lit. The lantern was produced at the end of the 19th century by the Belgian company Roche & Cie.

Nitedal matchbox

Nitedal's Tændstiksfabrik was founded in 1863. In the first years, the factory produced phosphorus matches, which were easily flammable and could easily be ignited against the leg of a trouser or boot. The safety matches had to be lit against a tear plate and were therefore more fireproof. This box has a tear plate. Nitedal's matches are today produced by Swedish Match.

Bryant & May matchbox

The matches had lighters at both ends for better utilization of the wood material. The factory was located in London where several thousand low-wage women and children worked. Working conditions were poor with health damage to teeth and bones due to working with phosphorus. It was women who stopped work in the first general strikes in Great Britain at Bryant and May in 1888 and in Norway at Nitedal in 1889.

Astral lamp

The first scientifically constructed oil lamp was patented in 1784. It has a hollow wick that supplies air to the flame, and the oil flows from the high-placed oil container to the wick. The lamp cast minimal shadows and was therefore used for reading and called a study lamp. Another name was "argand lamp" after the lamp's inventor. The lamp lacks a glass shade.

Moderator lamp

This French lamp was invented in 1837 and has the container for oil placed under the wick. A hidden pressure mechanism pushes the oil up into the burner.

Kerosene lamp

The lamp was called a round burner because of the cylindrical wick. It was submerged in kerosene in the lamp's glass flask. In the 19th century, several types of oil were in use. In the beginning, tallow oil, such as foul-smelling cod liver oil and whale oil, was most common. Later it was replaced by wood oil or oil made from coal. Kerosene was cheap and clean-burning, and kerosene soon replaced the other types of oil.

Gas lamp

The lamp is made of iron and polished brass and has a gas arm for one flame. It was manufactured by RW Winfield & Co in Birmingham in 1878. The factory also made tubular furniture such as chairs and beds. Gas for private lighting was not a success in Norway due to its high price. The lamp was a gift from the National Museum to The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology in 1931.

Night lamp

This brass electric bedside lamp is from around 1915. When electric lighting became common, several rooms in the house could be lit up. It became possible to carry out several activities regardless of the time of day. Reading in bed, for example, was no longer a fire hazard. The lamp shade is not original.

Street lights

The street lights helped make the outdoor areas safe after dark. Private property and public buildings were to be protected against "shady business". In Oslo, in the 1830s, the municipality established a separate lantern committee with the chief of police and the fire marshal at the head. Among other things, the committee ensured that the lights worked as they should. The lanterns had to be lit, extinguished and kept clean.

It started with 75 public oil lanterns in Oslo in 1734. In addition, private farm owners also set up lanterns near their properties. In 1848 the gas lanterns came, and in 1892 the first electric lamps were lit on the parade street Karl Johan with every other gas lantern and every other electric arc lamp. The different light sources existed in parallel for several decades. In 1929, the last gas lanterns were extinguished.

Lamp post for gas

In 1848, Oslo Gassverk was founded. Eleven street lights were set up from the gas plant's premises in Storgata to Stortorvet. This lantern is made of cast iron with neo-Gothic decor and is marked as number 10. Gas gave better light and was easier to maintain than the oil lanterns.

Lamp housing for street lamp

The first street lamps were oil lamps for fat oil, such as cod liver oil and whale oil. Farm owners and business owners set up lanterns that lit up streets and entrances. Municipal lanterns were also in use. The oil lamps shone dimly, could not tolerate cold well, and the need for maintenance and polishing of glass was great. In order to save on expenses, the time at which the lanterns were to be lit was strictly regulated. After 1881, new oil lamps were no longer purchased in Oslo. But they were still in use and were moved from the center to the suburbs.

Gas lantern "Regent"

The hanging gas lantern with seven burners was purchased by Oslo gassverk around 1915 from the leading manufacturer of gas lanterns William Sugg & Co in London. The lamp was a technological innovation with several composite flares in each dome to increase the amount of light, while perforated caps diffused the light. It also cast less shadow than the earlier gas lanterns.

Electric street lamp

The lamp was acquired by Oslo Lysverker in 1923. This was the same year that the municipality decided to electrify all street lighting in the city.

The city's parade street

Oslo's residents met at Karl Johan, where it was all about seeing and being seen. After 1892, the street lighting was a combination of tall electric arc lamps with strong light and low gas lanterns which gave a weaker but more pleasant light. The two variants are seen on the horizon towards the castle in the background.

Photo: Severin Worm-Petersen / The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology

Digging in the city streets

The gas lanterns were connected by pipes that had to be buried. The pipes also had to be regularly repaired. At the intersection of Prinsens gate and Nedre Slottsgate, an entire lamp post was replaced. The picture was drawn by architect Wilhelm von Hanno in 1862.

Photo: Wilhelm von Hanno / Fredrik Birkelund / Oslo museum

Carbon wire lamp from Hammerfest

In February 1891, Hammerfest became the first city in Europe with electric street lighting. The municipality decided that the profits from the town's alcohol sales should pay for this public purpose. Finnmarksposten described the event: "The brilliant lighting naturally brings great happiness to the people of the city, who in the evening go out in large numbers to enjoy and admire the magnificent light that is produced in such an unimaginable way."

Light in the workplace

The industry was an early adopter of electric lighting. The first time it happened was in 1877 at Lisleby Brug in Fredrikstad. Arc lamps were placed high up on the wall in the factory halls and shone brightly. Two coal pins stood against each other and a spark appeared in the space between them when the current was passed through. Open light sources such as oil, gas and charcoal sticks in combination with sparks from machines, oil spills and dust led to a fire hazard. When incandescent lamps were launched in the 1880s, the brightness became more stable and more pleasant to work in. The risk of fire was reduced by encapsulating the glowing coal wire in a glass flask.

The need for lighting was different in offices and retail than in factories. Here, too, the ceiling light was still most important, but at the same time a more flexible lighting was needed that made reading and writing easier.

Light bulb

Patented by Sigmund Bergmann in 1881 in collaboration with Thomas A. Edison who later bought Bergmann's American patents. Bergmann went back to Berlin, where a few years later he founded a lamp factory. It became part of Osram in 1919.

The Luxo lamp

In the interwar period, the incandescent lamp became a consumer product. Packaging and logo helped the consumer choose the right brand. In the advertisement for the D lamp, Osram claimed that the lamp had a lifespan of a full 1000 hours and gave 36% more light than the lamps that were usually used. The lamp was launched in 1935.

Osram D lamp

In the interwar period, the incandescent lamp became a consumer product. Packaging and logo helped the consumer choose the right brand. In the advertisement for the D lamp, Osram claimed that the lamp had a lifespan of a full 1000 hours and gave 36% more light than the lamps that were usually used. The lamp was launched in 1935.

Stretching of cables

The electricity also required a lot of space. Cables had to be buried in the ground or wires stretched between masts. The Norwegian Electricity Authority in Oslo was municipal and had responsibility for the city's electricity supply. Here, 35,000 volt cables are laid at the intersection Øvre Slottsgate – Prinsens gate in the summer of 1922.

Photo: Unknown photographer / The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology

Watch cabinet with model

Inside the peephole you can see a man preaching in front of a congregation, and a poster that says "Only the enlightened are not afraid of the shadow".

Model by Geir Christiansen

4. Consumption

Electric entertainment

The battle between electricity and gas took place in the kitchen. In the interwar period, the gasworks had largely been outcompeted as a supplier of lighting to industry and streets. But gas was well suited to home cooking, and many households had already invested in gas stoves. Nevertheless, the popularity of the electrical household appliances increased.

Electricity was clean and based on Norwegian hydropower and a growing national electrotechnical industry. Hygiene was also important, and it was pointed out that electricity did not produce cheese like gas and kerosene did. The electricity companies worked together with the manufacturers of electrical equipment, the housewives' organizations and public information workers to convince the housewives to cook electrically.

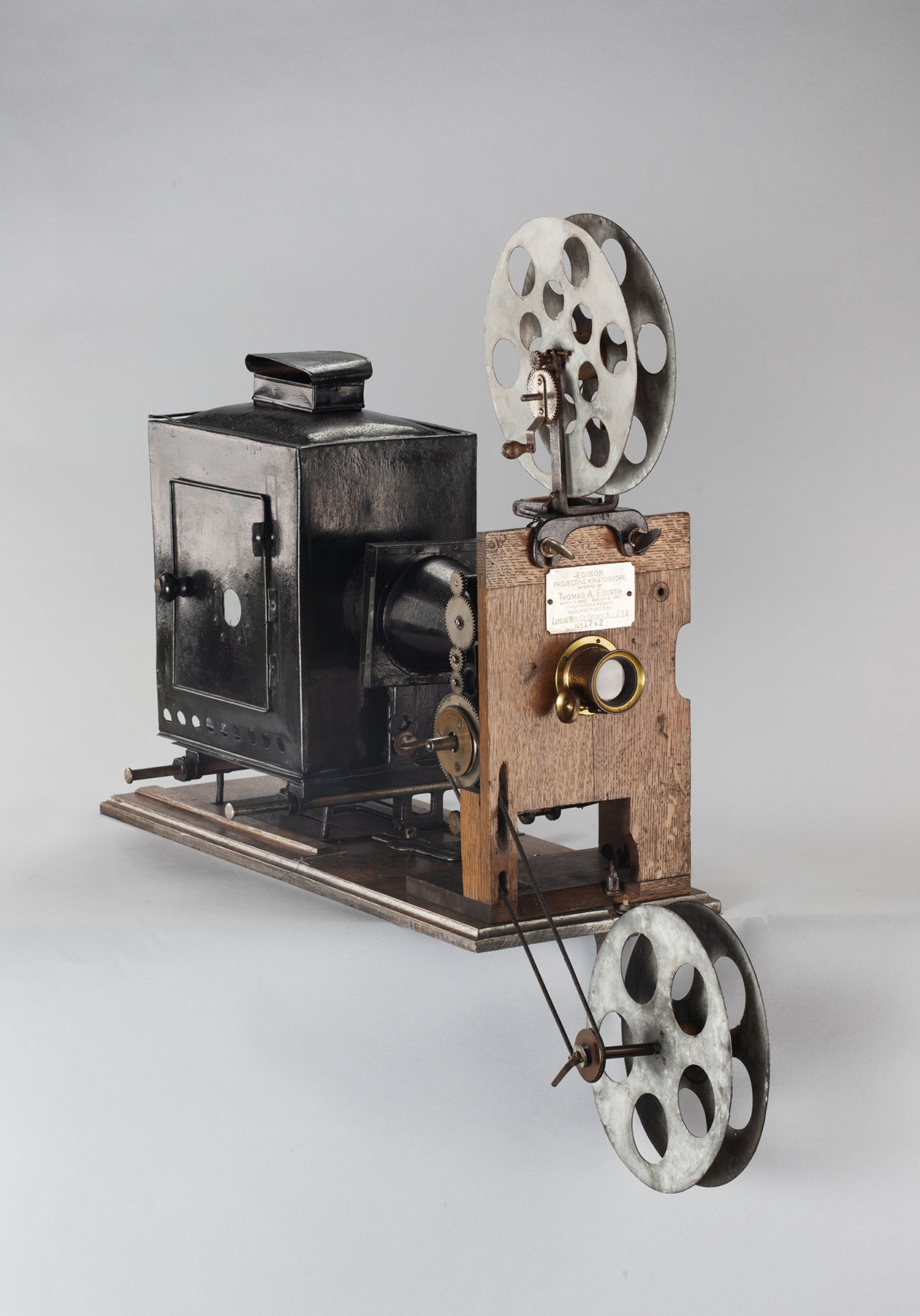

Edison's movie projector

Lars Fitjar was early on showing films in the Haugesund area. He traveled around with this movie projector and a gramophone in houses of worship and other places of assembly. The projector was also used for slide presentations. The film rolls were cranked by hand. He often had to make his own electricity as many places were still without electricity. The projection light was formed with the help of gas.

Cinema poster

Most of the films shown were foreign and were bought directly from the USA or a dealer in Oslo. There was also an early Norwegian film production. The price for a child's ticket was 10 øre in 1905, which corresponded to the price of a liter of milk. Cinema was very popular. The venues were filled, and the audience loved seeing the live images.

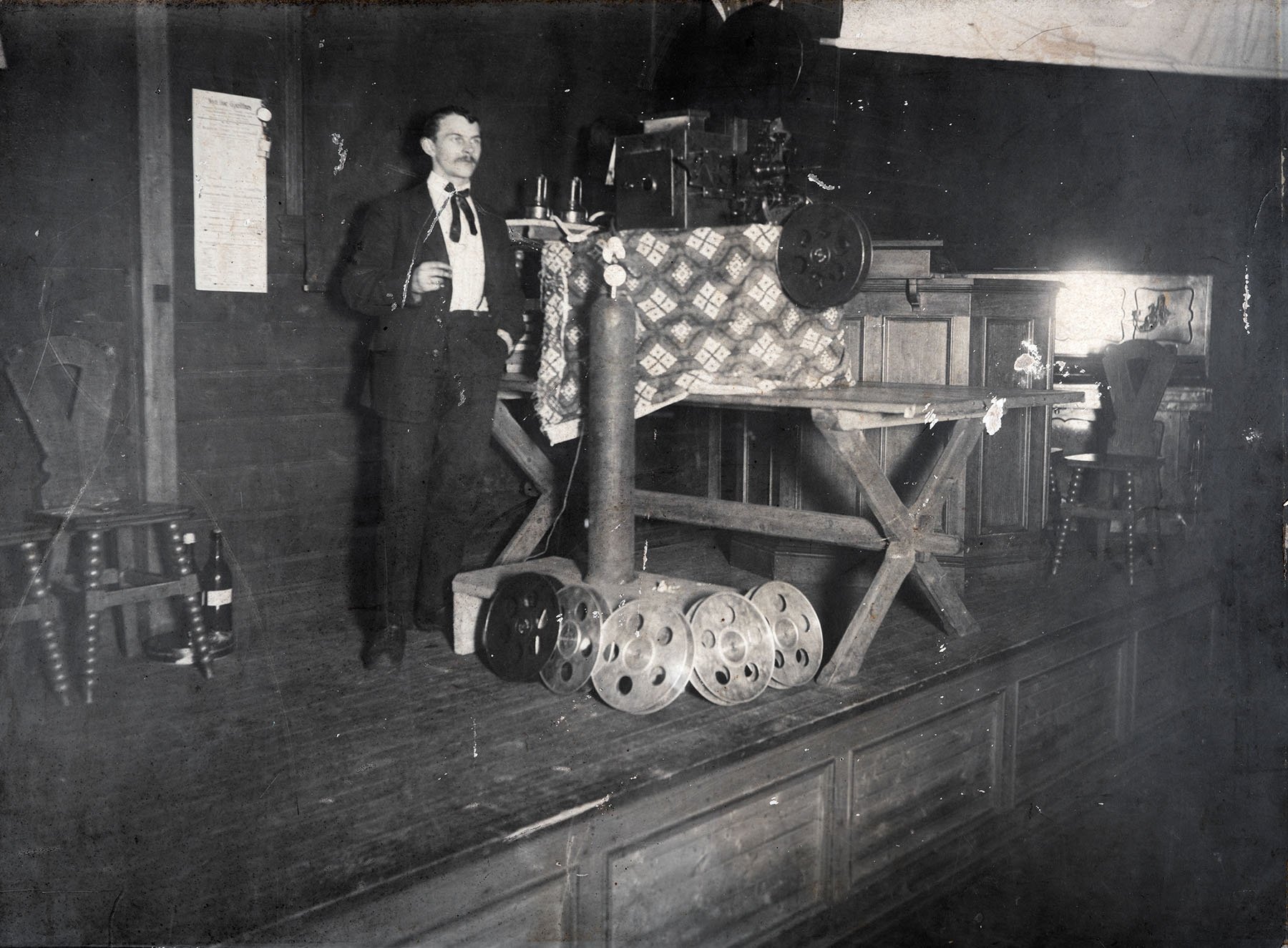

Film screening in Osterhaus' street

Norvald Bjerke showed films in Oslo and Bergen around 1910. In addition, he himself played the accordion together with the virtuoso Øivind Andersen during the performances.

Photo: Unknown/ Norsk Teknisk Museum

The battle for the housewives

Electricity contributed to new forms of entertainment. The state radio company Norsk Rikskringkasting (NRK) was founded in 1933 after a few years with private companies. The sound was sent from the studio via local radio transmitters out to the thousands of homes. The first radio programs contained music, radio theatre, church services and public information.

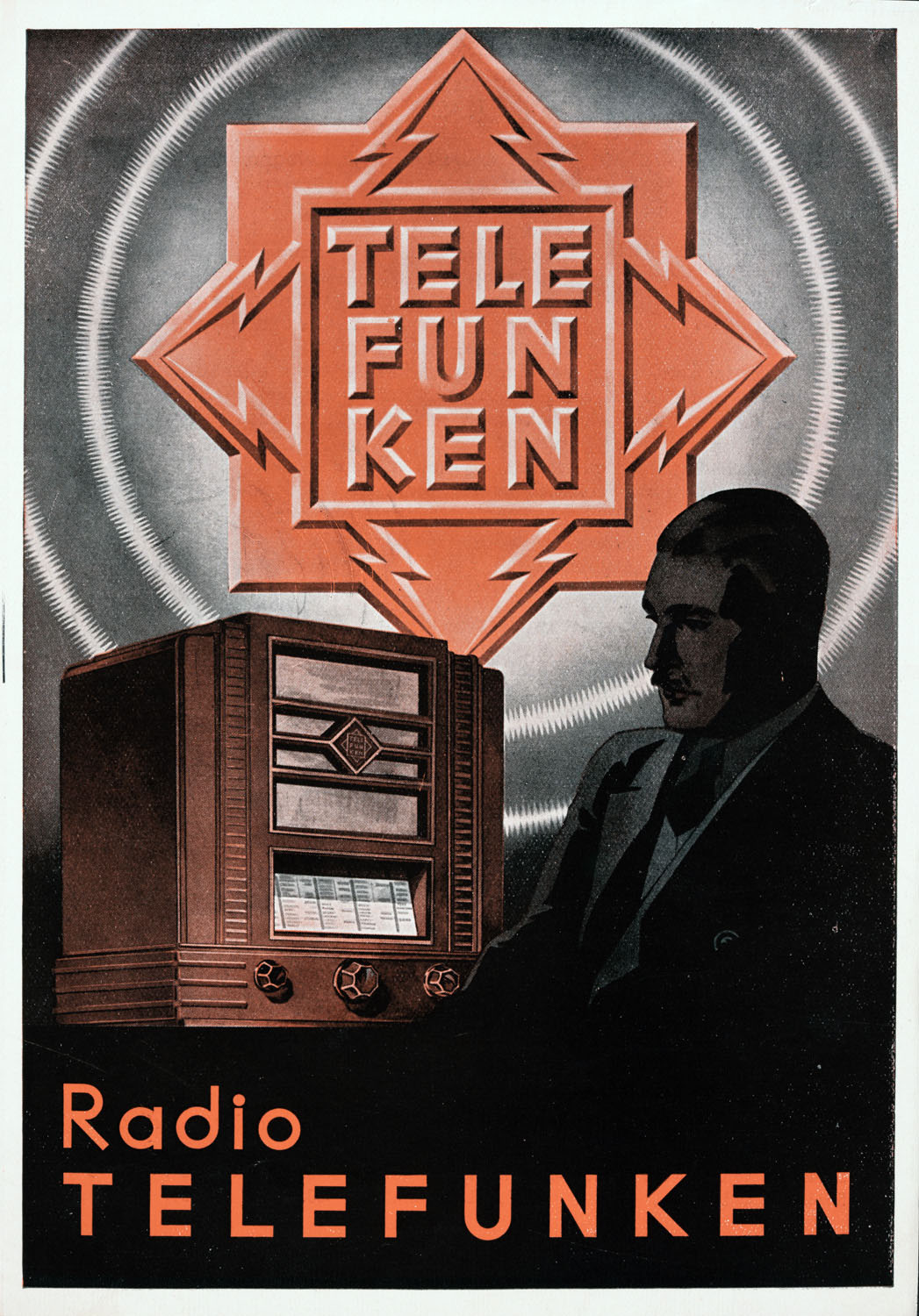

The radio was given a prominent place in the living room and became an important part of the interiors of the time. At the start, the market was dominated by radios from foreign companies such as Telefunken and Philips, but eventually several Norwegian radio factories were also established.

Electric stove

In 1932, the Oslo company Per Kure launched a cheap electric stove that fit into most kitchens and in families with less good finances. Electric plates were a technical innovation and saved both electricity consumption and space. The smallest model Elektra stoves had two hotplates, an oven and a warming cupboard for the plates.

Three-part cookware

The right cookware was important to make use of the hotplates on the stove. An aluminum cooking pot with a flat bottom was recommended. They conducted the heat the best. In addition, it was important that the entire plate was covered. A cooking vessel in three parts meant that potatoes, vegetables and meat or fish could be cooked simultaneously on the largest plate.

Electric light advertising

The lamp was an advertisement for Elektra stoves and cooking appliances produced by Per Kure. The drawn figure was used in many of the company's advertisements. The lamp came from Cæsar Lundberg's business in Bryn, which sold electrical equipment in the early 1930s.

Kerosene-powered toaster

Tourism grew at the end of the 19th century. The bath hotel and sanatorium on Hankø opened in the summer of 1877. There were also rental villas where guests cooked their own food. To satisfy the tastes of the foreign tourists, toasters were acquired, but these were powered by kerosene before electricity came.

Boiler for kerosene

Cooking appliances powered by petroleum or kerosene meant that food boiled quickly. The fact that they were also economical in use contributed to them becoming common in many kitchens in the early 20th century. The downside was that they were highly flammable.

Gas cooker Model 45

Gas was well suited for cooking. Gas stoves were most common, but there were also small and simple gas hobs.

Advertisement for Rex stove

Elektriks Bureau was the leading electrotechnical company in Norway. It was early on in producing kitchen items in the Rex series. Henriette Schønberg Erken was a pioneer in the housewifery profession as a housekeeper teacher and cookbook author. She gave classes and demonstrated household electrical appliances, as in this 1926 advertisement.

Photo: Unknown/ Norsk Teknisk Museum

Advertising for electricity and gas

The dream of a cozy home was a central motif in advertising from the interwar period. Heat was needed for both cooking and heating. Streamlining housework was also an important selling point. The advertisement was for Norwegian-made electrical items and German and British gas stoves that were sold in Norway.

We who cook electrically

Gerd Wibord Thune was employed by the Norwegian Electricity Works Association to train Norwegian housewives in cooking using electricity. The cookbook was published in 1939. During the Second World War, the book came out in new editions with emergency recipes and advice on how the housewife could save on both electricity and food.

Radio in every home

In the post-war period, shaving with electric machines became popular. Dry shaving, as it was called, challenged the traditional shaving with brooms, knives, soap and water. The shaver was easier to use and it was claimed that it was also more hygienic. Spill water and the dangerous knives disappeared. The launch of the new consumer product was followed by major advertising campaigns.

1950s commercials were heavily gendered. Female consumers were the target group for most of the new consumer goods. The exception was the shavers intended for men's facial hair. The shaving machine advertisement gave identity to the male consumers by playing on masculine appearance and knowledge of shaving, electricity and mechanics.

A Latvian radio

The radio Vef super MD39, manufactured in Latvia in 1939, was given to the museum in 1964. Originally it came from the "National Committee for the Disposal of Stray Radios". The committee distributed the radio sets that were not collected after the war. The Jews were the first to have their radios confiscated during the war. Over half were killed in German concentration camps. Perhaps this device was owned by a Norwegian Jew?

Trolleye

The radio tube or electron tube of the type Telefunken A M2 DRP was used as a troll's eye in the radio. This was a station meter where the electron tube lit up when the radio was correctly tuned to the desired station. The lamp flashed when the viewfinder was out of focus and the sound was jarring.

Advertising for Telefunken radio

In the 1930s, the German radio factory was one of the largest suppliers of radios in Norway. The distinctive logo was designed in 1919 and is still in use. Listening to the radio became a leisure activity and a source of information and education on a par with reading books and newspapers.

Illustration: Unknown/ The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology

User manual for Telefunken Stratos 34

Stratos was a series among Telefunken's many radios. Emphasis was placed on easy operation of the radio, good sound, and "the beautiful appearance that makes it fit in any home".

Photo: Unknown/ Norsk Teknisk Museum

Body care

In 1896, the year after the world's first cinematograph opened in Paris, live film was shown at Circus Varieté in Oslo. Eight years later, the first cinema was established in Stortingsgata. In Oslo alone, over twenty cinemas were in operation around 1910, and the tendency was the same across the country. Anyone with a projector and access to film could set up a cinema wherever it suited them. In 1913, Norway got its own film law. A municipal permit was then required to show films. Municipal cinemas were created, and the small private cinemas disappeared.

The first films were short and often contained news or humor. Some of the films had daring content by the standards of the time. There were silent films, accompanied by gramophone or piano music.

Chic shaver

Jacob Schick designed the first electric shaver. It was put into commercial production in 1931. The manufacturer continued to develop the concept of dry shaving. The American razor brand still exists in 2023.

PhiliShave "The Cigar"

Philips launched its first electric shaver in 1939, the so-called PhiliShave. Beyond the 1940s, the machines became available to more and more people. In the advertisement, the term dry shaving was used, and the method was supposed to be gentler on the skin. The shaver was nicknamed the Cigarette.

PhiliShave "The Egg"

In 1953, Philips' first battery-powered shaver arrived. It could therefore easily be taken on trips. The mirror on the battery box was also handy to check the result of the shave. Two years earlier, Philips had launched the model with a double head which was a new technology in electric shaving.

Remington "Contour"

Remington Rand invested in razors from 1937. The brand was known from, among other things, typewriters, and the razors quickly gained a good position in Norway as well. In the 1950s, the company carried out extensive marketing with its own installment system and a trade-in scheme for older shavers. The slogan was: "Let shaving be a pleasure!"

Braun DL 3 1955

The German electronics brand Braun started producing shavers in the 1950s. The company invested heavily in industrial design, among other things by working on ease of use. The logo was also designed in the 1950s.

User manual for Telefunken Stratos 34

Stratos was a series among Telefunken's many radios. Emphasis was placed on easy operation of the radio, good sound, and "the beautiful appearance that makes it fit in any home".

Photo: Unknown/ Norsk Teknisk Museum

5. Magic

The secrets of the atomic nucleus

The secrets of the atomic nucleus

In the 1930s, nuclear physics was a new and unexplored field. Einstein had already established that large sources of energy lay hidden in the atoms. Many had ideas about what nuclear power could be used for. Was this the solution to the world's energy crisis? Scientists looked with optimism at the possibilities of nuclear physics - in a time before the atomic bomb had been invented.

In 1932, scientists split atomic nuclei in the laboratory for the first time. They managed this with the help of a machine that accelerated particles to a high speed. Now the scientists could control a nuclear reaction, and carry out experimental nuclear research. Ellen Gleditsch was the one who introduced the field of nuclear physics in Norway. In the 1930s, any self-respecting physics laboratory would establish an acceleration laboratory. Physics professor Johan Holtsmark at the Norwegian Institute of Technology initiated the construction of a Van de Graaff accelerator. He had big visions for what the machine could achieve:

"(...) if mass could be destroyed and the energy that would be freed by the destruction extracted. It didn't take many grams to supply the whole of Norway with electricity for a year." ( Technical Weekly , 1935)

Generator, part of Van de Graaff accelerator

This is the second Van de Graaff generator in all of Europe. The machine was built at Norway's Technical College (NTH), between 1933–1937, under the direction of Johan Holtsmark and with help from Odd Dahl. It could create high voltage up to half a million volts. The goal was to create enough energy to shatter atomic nuclei and create a nuclear reaction. The high-voltage facility at NTH was the start of accelerator-based nuclear physics in Norway.

Acceleration pipe

An acceleration tube was connected to the dome of the generator. Through the tube, protons were sent at high speed towards a target disc of light elements. It created a core reaction. With advanced instruments, the physicists could measure what happened next. Accelerator-based nuclear physics, with its need for space and infrastructure, was the start of the huge nuclear research laboratories as we know them today.

Photo: Unknown/Museum for University and Science History

Van de Graaff at the World Exhibition in 1937

At the World Exhibition in Paris, the latest in technology was showcased, and in 1937 a Van de Graaff machine was self-written. During the demonstrations, purple sparks shot out of the dome to the great excitement of the audience. The machine on display in the Palais de la Decouverte could produce up to 5 million volts. That is ten times more than our machine, which was also completed in 1937.

Drawing: Boutterin/Bridgeman Images

"Making energy via fusion technology has been a dream for decades. But it has also been just that: a dream. Now it can finally seem that the dream can become reality."

Fusion

Creating energy in nuclear reactors can be done in two ways, through fission or fusion. Fission splits atomic nuclei, while fusion fuses particles together. The fusion process has been researched since the Second World War, and in 2022, fusion scientists had a major breakthrough: They created a nuclear reaction that gave off more energy than they had added. This shows the possibility of a self-sustaining energy source, i.e. a kind of perpetual motion machine. But the fusion experiments are very resource-intensive. They require enormous pressure and over 150 million degrees Celsius, which is much hotter than the core of the Sun.

Photo: Damien Jemison/AP, NTB

To make the wheel turn all by itself

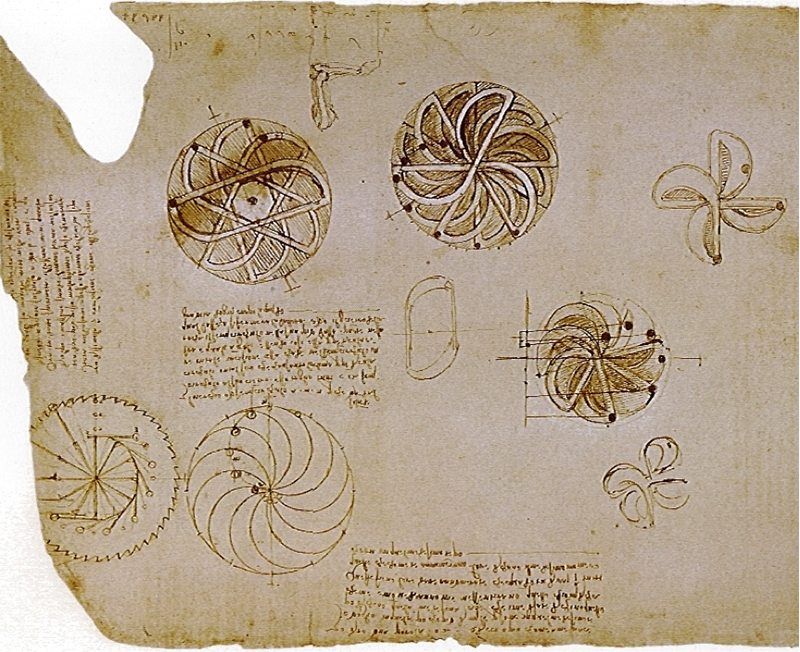

Perpetuum mobile comes from Latin and means "perpetual motion". The goal of the perpetual motion machine is to be able to run on its own, i.e. perform mechanical work without the help of an external energy source.

The first attempt at a perpetual motion machine that we know of was developed by the Indian mathematician Bhaskara, around the year 1150. In the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci drew sketches of perpetual motion machines, but he also realized that it was impossible to build such a machine. This could not be explained scientifically until the mid-19th century. The laws of thermodynamics state that some energy will always be lost in the transformation of energy from one state to another. The laws limit the efficiency of a machine to less than 100 percent. This means that the perpetual motion machine's principle of performing work without the input of energy is impossible. However, this has not stopped inventors from trying, as the perpetual motion machine at The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology is an example of.

Generator, part of Van de Graaff accelerator

The perpetual motion machine was built at Vulkan Jernstøberi and mechanical workshop in Oslo, probably between 1890–1930. The machine was made to order, but no one picked it up. Perhaps it was because the inventor could not afford to sign it off or that the person had lost faith in the project along the way. We know neither the customer nor the machine's construction drawing. Gifted to The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology in 1939.

The cover of a catalog for the world exhibition.

Illustration: A. Simon.

Drawing: Boutterin/Bridgeman Images

Leonardo da Vinci's notebook

The drawing shows a sketch of a perpetual motion machine. Small balls inside the wheel structure were supposed to make the wheel go around by itself.

Drawing: da Vinci/ The British Library.

Photo: Unknown/Museum for University and Science History

Energy as a universal measure

The German chemist Wilhelm Ostwald (1853–1932) believed that all phenomena could be explained based on the theory of energy. In his theory of energy - energetics - he included not only nature and matter, but also social conditions such as culture and economy.

The project was not about creating an inexhaustible source of energy, but about energy efficiency. The aim was to free man from the coercion of nature. Ostwald believed that energy was a resource that man had to master. He linked the ability to manage energy in an efficient way to a country's cultural development. Ostwald did not distinguish between different cultures, but between the cultural level of different countries. The level at which the country was was assessed based on its energy stock, the degree of utilization and the distribution of it in society. The countries that mastered this best were at the highest level of civilization.

Energy and culture

Book by Wilhelm Ostwald as was translated into Norwegian in 1911 and published by Aschehoug publishing house. The historian Edvard Bull called Ostwald one of the sharpest scientists of his time in his review of the book. Today, Ostwald's theory of energy is considered a curiosity of the history of ideas.

Battery

Was produced by the Belfa electrochemical factory in Bergen between 1900–1920.

American dollar bill

During the economic crisis of the 1930s, some American engineers launched the idea of a new economic system. Instead of a system based on the gold standard, where the amount of money is in proportion to the central bank's gold reserves, they proposed that the value of money should be linked to the amount of energy society had at its disposal. The main point was that the energy reserve of, for example, a sack of coal is constant, while the monetary value of the coal changes over time. Switching to an energy currency would make the economic system more predictable, they believed. Several Norwegian engineers supported the idea.

6. Norway in a fossil world order

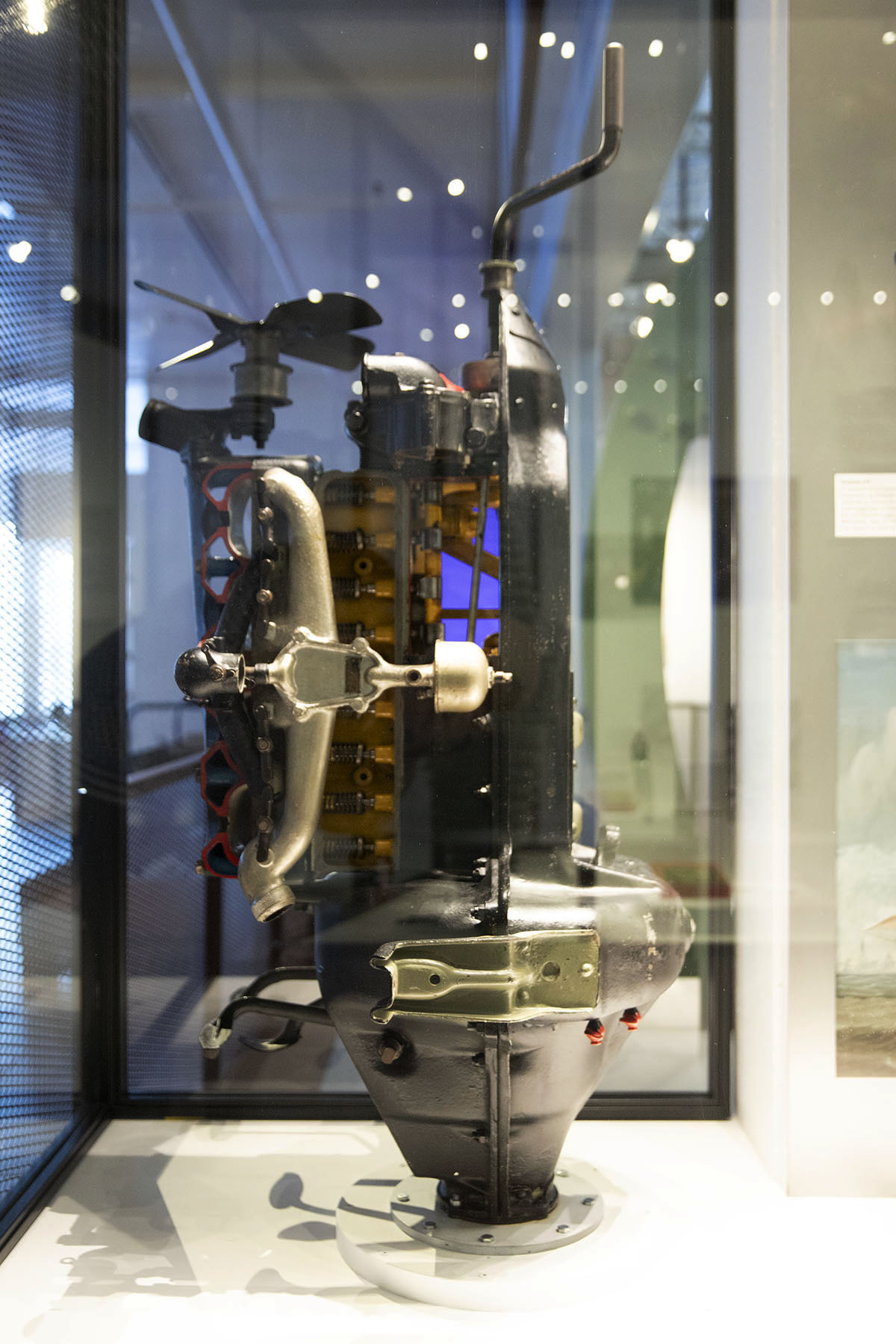

Car engine, 1910-1930

The T-Forden is one of the first mass-produced cars. It was equipped with a 4-cylinder engine that produced 20 horsepower and a top speed of around 70 km/h. In the internal combustion engine, chemical energy is converted into mechanical energy. The spark from the spark plug ignites the gasoline gas which pushes the piston inside the cylinder, which in turn pushes the car forward. The T-Forden could be powered by petrol, kerosene or ethanol.

The fossil sea

In the 19th century, Norwegian shipyards built wooden ships. Towards the end of the century they were replaced by steel ships powered by coal-fired steam and in the 20th century the petroleum engine. The shipping fleet has been one of the world's largest. Norwegian ships have transported fossil fuels such as coal, oil and gas as dry cargo and in tankers. The ships have transported coal from England and Germany to the railway, gas power plants and factories in Norway. Driven by coal-fired steam engines and diesel-powered motor ships, raw materials such as timber, fish and whale oil have passed from Norway to customers all over the world. Motorized whaling boats and fishing boats have harvested from the sea, and from the late 1960s oil and gas have been brought up from under the seabed. The ships not only transport fuel, raw materials and goods to and from Norway. They are the hub of an international network that has made the world increasingly fossil-fueled.

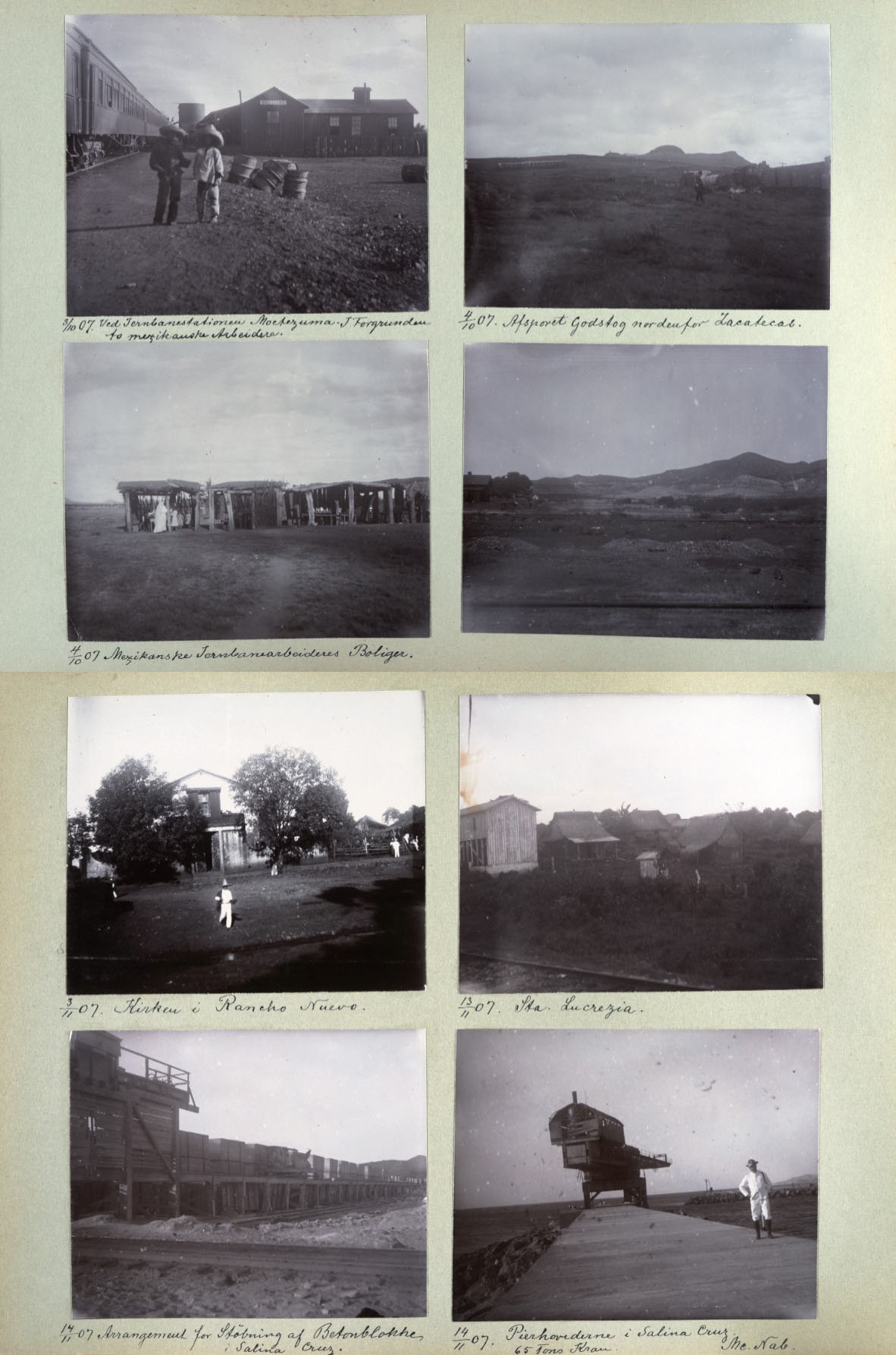

Construction of the Panama Canal, 1907

The Panama Canal carries shipping traffic through six double locks on the way between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The canal opened to traffic in 1914. It was originally intended that the polar ship Fram was to be the opening ship, but the opening was so delayed that the schooner returned home to Norway. In 2016, the canal was extended with a parallel run that takes larger ships.

Theodolite

A theodolite is an instrument for reading horizontal and vertical angles and is used in land surveying. This was used during the construction of the Panama Canal. The challenging construction started in the 1800s. Over 27,000 workers are believed to have lost their lives up to the opening in 1914.

The entry to the Suez Canal, 1890-1915

The Suez Canal connects the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. The canal opened to traffic in 1869, cutting travel time between Europe and Asia by about a month. Ships with a length of up to 275 m and a width of 70 meters can pass through the channel. They can transport up to 1 million barrels of oil or other goods of up to 200,000 tonnes.

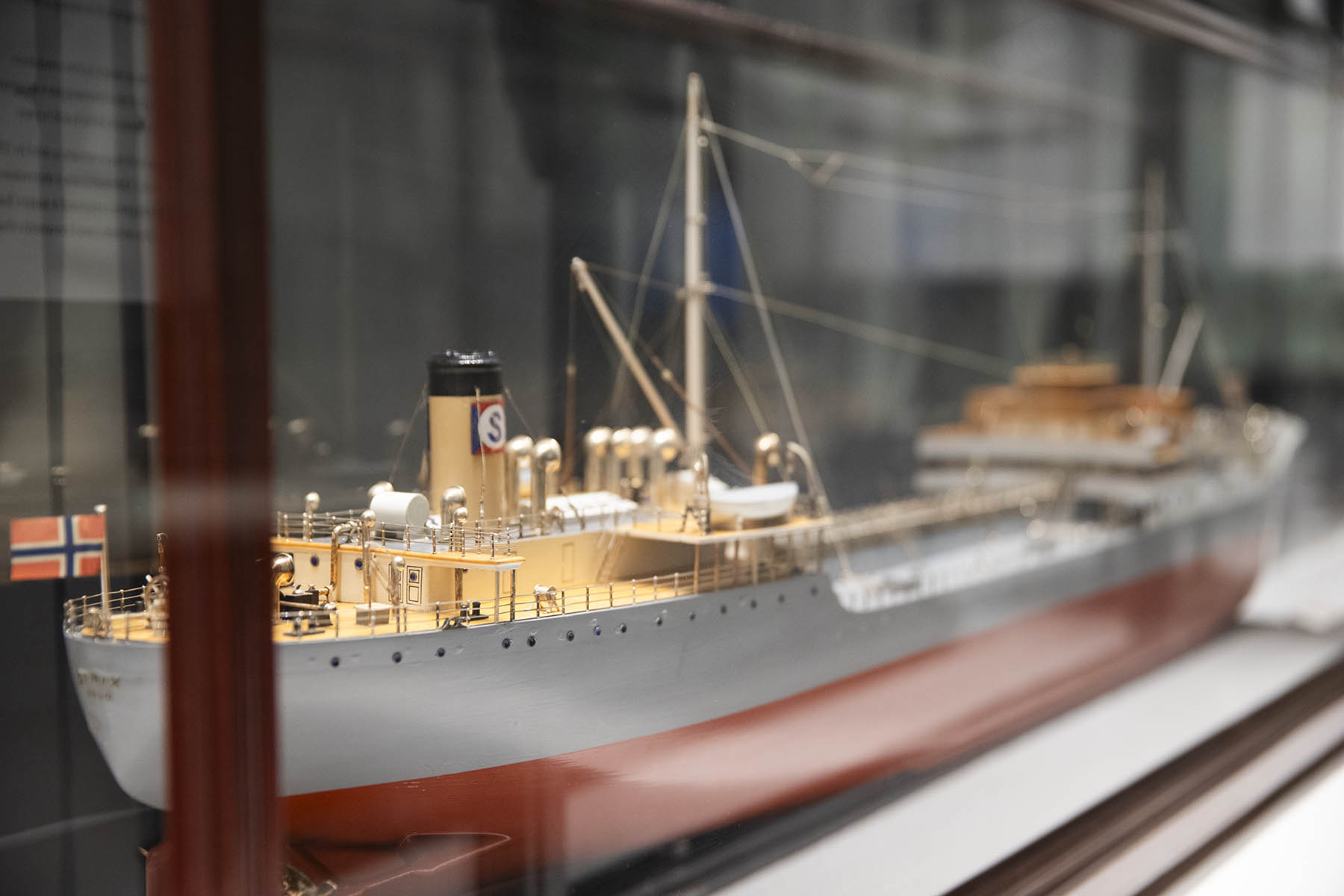

Bark "Lindesnæs"

In the winter of 1877–1878, the sailing ships "Jan Mayn", "Stadt" and "Lindesnæs" were converted into tankers at Fagerheim's shipyard in Tønsberg. The cargo spaces on the schooners were divided into watertight bulkheads and oil taps on deck. Although the steam tanker was developed at the same time, sailing tankers were built into the 20th century. Oils and petroleum held up well and could withstand long voyages, and the shipowners saved on fuel expenses.

Kerosene jug

Until the beginning of the 20th century, petrol, kerosene and other oil products were transported as bulk cargo in jugs and barrels on board ships. The ship itself was like a giant container that transported the fuel from production sites abroad to large ports such as Oslo and Bergen and further out to trading points along the coast.

Timber reception in Gjøsvika

The copper works at Røros had a great need for timber in the extraction of ore, in desulphurisation and for smelting and refining the copper. After the Røros Railway opened in 1877, imported coke could be used. Deforestation stopped. Elsewhere in Eastern Norway, the railway facilitated the transport of timber and opened up new areas for forestry.

Model of NSB steam locomotive 2a no. 16

Three locomotives of this type were delivered to Kongsvingerbanen in 1861. After the opening of the main line between Kristiania and Eidsvoll in 1854, there was great enthusiasm for the railway. It was unimpaired until the 1920s, when roads and road construction came into the driver's seat. The railway drastically reduced transport costs, and also changed settlement patterns with the emergence of new towns along the lines.

CREDIT

CREDIT HERE

"Travel in Mexico", 1907

In 1907, the Norwegian engineer and officer Ole Wilhelm Lund traveled to Mexico. He was to investigate the possibility of building a railway from Mexico City to the Pacific Ocean. Since the 1870s, Lund had been central to the development of Norwegian railways, including the laying out of the Bergen Railway's high mountain crossing and the construction of the Ofot Railway and the Sulitjelma Railway.

Charcoal drawer

The coal burns and causes water to boil. The heat energy in the steam is transformed into a mechanical force that propels the locomotive forward. The coal is stored in a tank on the locomotive or in a separate carriage and must be shoveled into the combustion chamber. From the beginning of the 20th century, coal was gradually replaced by diesel and electricity. In 1971, the last steam locomotive was taken out of service.

Looking for coal

Norwegian coking plant, 1965

In 1961, Norsk Koksverk was established in Mo i Rana and the vision of Norwegian coke was finally realised. At the plant, coal from, among other places, Svalbard was further processed into coke. The quality of the coke was debated, and in 1988 the plant was closed down.

"Nightshift" by Sverre Knut Johansen

Recordings from various wagons and alarms attached to them have been sampled and processed and, together with other sounds from the Coke Works, form the foundation of the work "Nightshift". The music is accompanied in the film by video recordings of the work made by Oddbjørn Johansen before its closure in 1988. "Nightshift" was first released in 1999 on the album The Source of Energy.

Annexation sign

Excerpt from "Arctic Mining" 1974

From the mines on Svalbard, coal is transported by ship to thermal power plants in Longyearbyen, and to the chemical and metallurgical industry in Norway and Europe. At the beginning of the 20th century, it was hoped that the coal deposits on Svalbard would cover the need for coal in mainland Norway. Despite the fact that coal was important in steel production at the iron works in Mo i Rana, it has always been necessary to import coal.

Produced by NRK.

From Ny-Ålesund, 1936

Svalbard was a male society of miners and white-collar workers. The workers were not allowed to bring their families with them. It was a good thing reserved for office workers. On 7 July 1929, the first four working women traveled to Longyearbyen. The women worked in care, supply and cleaning. Only in the 1970s were women allowed to work in the mines

"Jacob Kjøde" arrives in Harstad

In May 1949, "Jacob Kjøde" docks in Harstad. On board are the coffins of 15 miners who lost their lives when methane gas ignited coal dust in Ester III in Ny-Ålesund on 4 December. Accidents and explosive fires have claimed the lives of more than 185 workers in the Norwegian mines on Svalbard.

Miners at work in mine 5 in the 1960s

Down to 300 metres, the miners work in mountains with permafrost. Coal and stone lie in layers. The thickness of the coal layer determines the working height. In the Svea mine, the coal layers are up to five meters thick, while the height in the mines at Longyearbyen is less than one metre. When the coal disappears, pistons are set up. They must carry the mountain that presses down.

GAS BURNER

The fossil body

Shower

The work in the mines on Svalbard and in the gas works was dirty. At the end of the working day, the workers washed themselves in buckets or basins of washing water. It often happened that someone went home without washing. The work clothes could soon stand on their own due to coal and stone dust. With warm water and a shower, it gradually became easier to wash the body clean of dust and soot.

Boot lungs

This is an x-ray of the lungs of an elderly man who worked in a coal mine. Dust can cause an inflammatory reaction in the lungs that forms scars. Gradually, breathing becomes worse, and the risk increases for other lung diseases such as cancer and tuberculosis. Many types of work such as mining, demolition work and textile production result in high exposure to dust.

Construction of a gas bell for Oslo gasworks

When coal is heated to 1100–1200 degrees, a gas synthesis of hydrogen, methane, carbon monoxide and ethylene is formed. It is called lighting gas or city gas. It was not possible to fully adapt production to consumption. The extra gas was stored in gas containers, so-called gas bells, which stood in pools of water. The largest bell at the Oslo gasworks was built in 1925 and held 60,000 gas.

Gas meter

The gas works in Oslo opened in 1848, and during the 1850s gas works were established in Halden, Trondheim, Bergen, Kristiansand and Moss. Pipelines that brought the gas from the gas plant to consumers were laid in the ground. Occasionally, leaks could occur. Gas meters like this were used in the laboratory at the Oslo gas plant and could measure gas emissions.

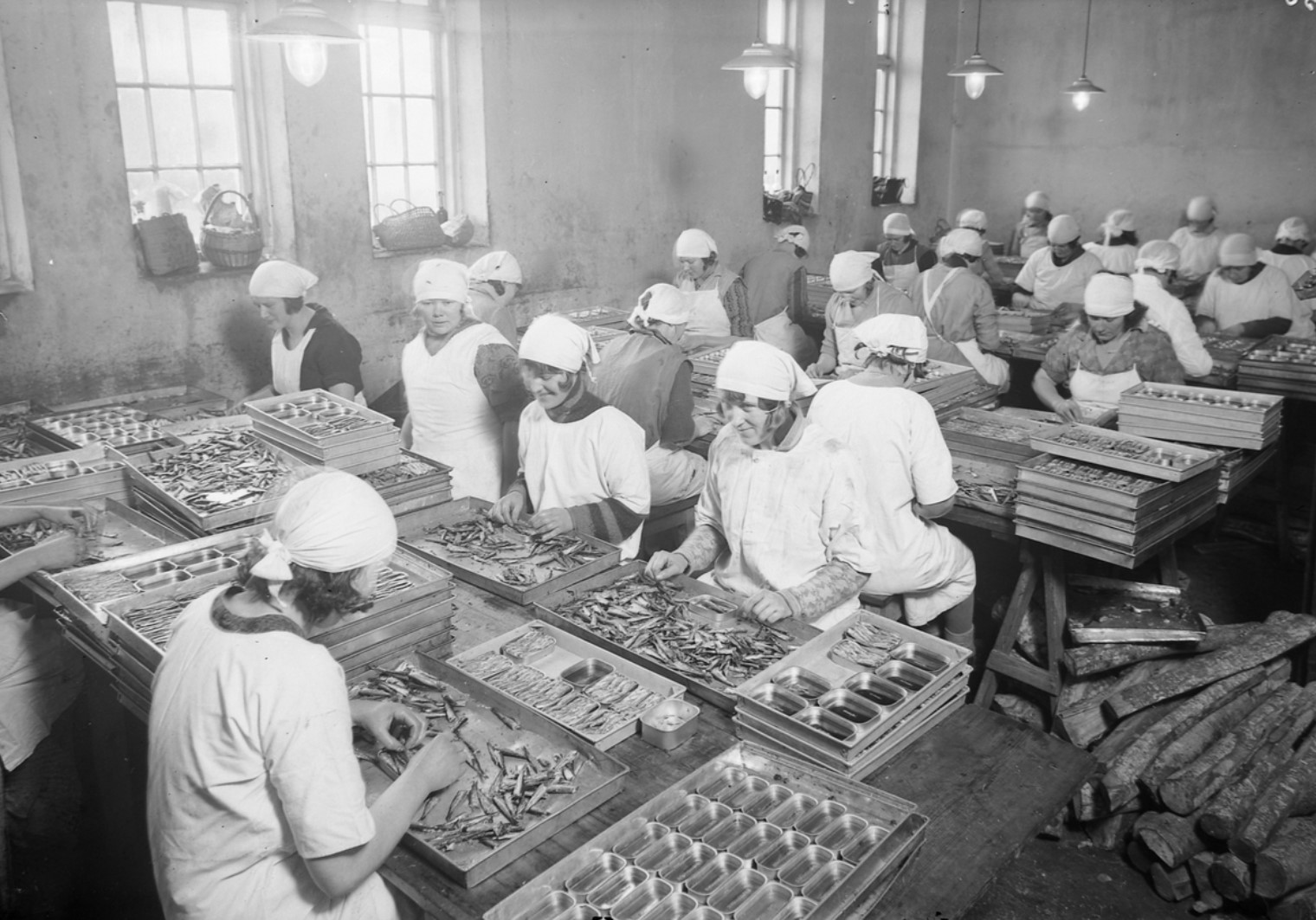

Workers at the retorts in Oslo Gassverk, around 1930

Retorts were furnaces that were filled with coal and burned at 1100 degrees for 7 to 8 hours without the supply of oxygen. Teams of five men scraped the white-hot coke out and down to cool on the floor below. When one retort was emptied, it was on to the next. Sweat poured, and canvas mittens protected against the worst of the heat. After 1920, the operation became more mechanized.

Coke box

A byproduct of burning coal into gas was coke. The coke was sold from a pile at Ankerløkken. It could be up to 10 meters high. It was possible to have coke delivered home, but many also collected it themselves with a cart or sledge. The gas utility did not cover the need for coke, and imported coke could also be bought in own outlets.

When the sea was emptied of oil

From flange plan in Grytviken, South Georgia, around 1930.

The whaling industry was a man's world. The whalers had to be tough and keep calm in the face of extreme nature and dangerous work. The whale was everywhere. When the flanges cut holes in the abdomen, the entrails spilled out. Whale remains lay like a greasy film over everything. The stench settled in their clothes, in the bed and in everything they tasted.

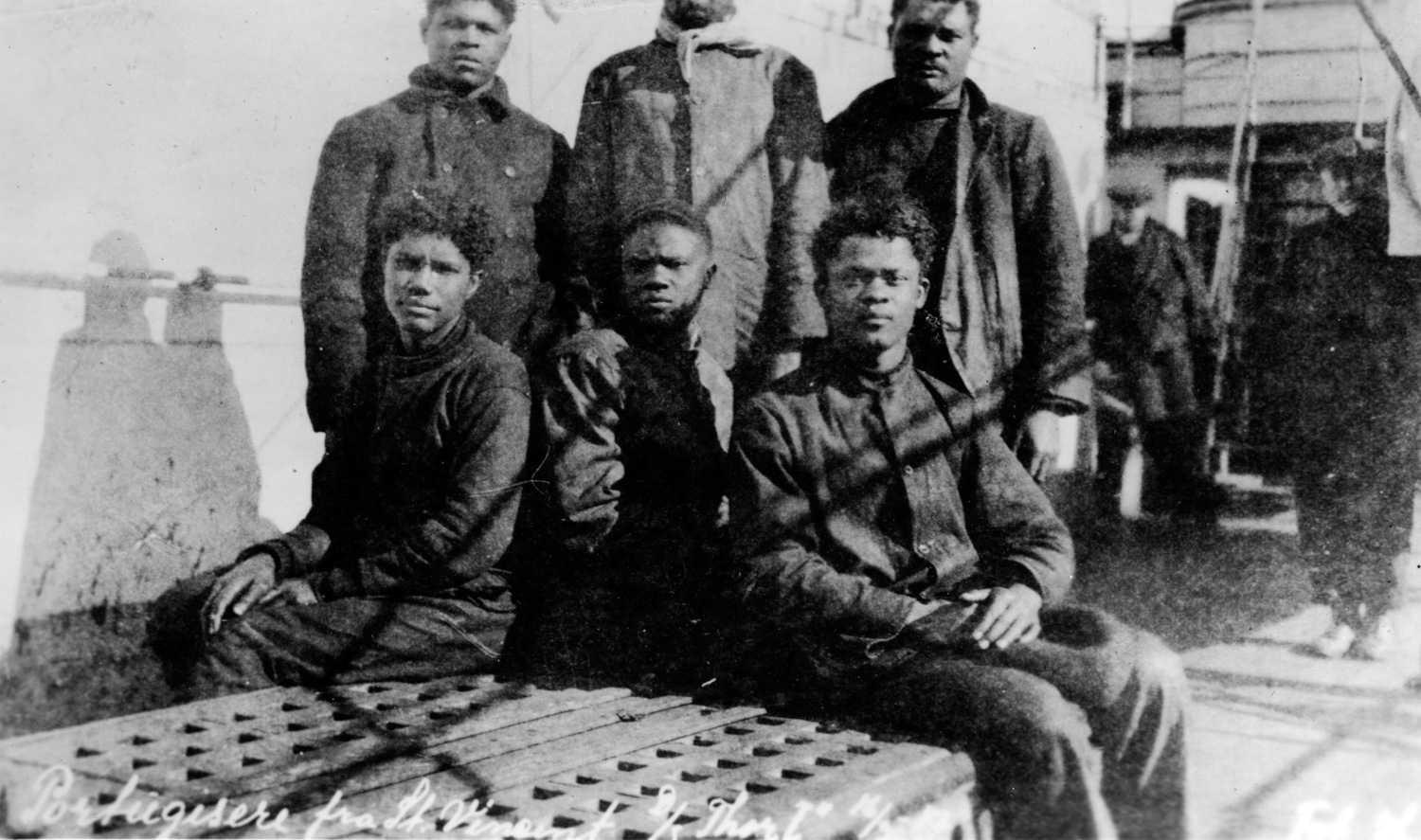

Men from St. Vincent in Cape Verde on board "Thor II", 1916–1917

In the Cape Verde Islands, off the coast of West Africa, the schooner stopped to fill with coal. Cheap labor also came on board. They did the heaviest work. They shoveled coal, carried crates, hauled materials and shoveled graks, the muddy remains of whale oil production. The African workers were not part of Skuta's community. You didn't mix with them.

Mining lamp

Until the middle of the 19th century, most of the whale oil found its way into the oil lamps. The oil from fishing along the coast in the northern regions was in demand in Northern Europe and the USA. In the home, the lamps were often open bowls, while closed lamps were used in mines. The oil was filled in the container and burned through the wick at the tip. This lamp provided light in the cobalt mines at Skuterud in Modum.

The whaling ship D/S "Hav"

D/S "Hav" was built at Akers mek. Workshop in 1931 for the shipping company A/S Polhavet in Tønsberg. The boat was powered by . Fast steamships allowed the whalers to catch swift whale species. From the 1920s, the dead whales were taken on board in floating cookers, and the conversion of whales into oil could take place at sea.

Harpoon

The shooter takes aim and fires a shot at the whale. The harpoon hits and penetrates the animal's body. Lina braces herself and triggers the grenade, which explodes inside the animal. Sometimes the whale is killed in seconds, other times it takes hours. The grenade harpoon was developed by Svend Foyn and was important for the industrialization of whaling in the 1860s.

Whale ears

In industrial whaling, the rush was great, and the most readily available oil was in blubber. Once the blubber was peeled off, the rest of the whale was dumped, and the hunt for the next whale continued. Around three million animals had to pay with their lives. Some species disappeared forever, others still balance on the edge of extinction.

Energy management

Fossil fuels such as coal and oil can be used when needed. Water and wind follow the course of nature. If the river freezes or dries up, the machines must be stopped. With the steam engine, the factory can run independently of the weather and seasons.

Factories with steam engines required many people to perform work at the same rate. Previously, work had been about carrying out a task and the workers had been paid for the amount of planks cut or yarn spun. Now work was linked to time, and the workers were paid for the time they cut or sawed. The day was divided into working time and leisure time.

Thermodynamics emerged as a field of knowledge in the 19th century. It helped to link energy, efficiency and work together, and provided a scientific basis for the engineers' optimization of the machines. From the factories, the emphasis on productivity and efficient energy utilization spread to other parts of society.

Coke collection, 1919

Managing energy resources was not just a matter for companies or the state. Energy had to be managed in the household as well. The women were often responsible for coke, coal and wood for heating, lighting and, not least, cooking, where raw materials had to be converted into energy-giving nutrients and ensure performance in the work.

Indicator for steam engines

An indicator shows how the gas pressure in the steam engine varies. The variations were automatically recorded on a sheet of paper. Engineers used the diagram to check that the machine was working as well as possible and how much work capacity it had. The work to improve the efficiency of the steam engine was a starting point for the field of thermodynamics.

Stopwatch

As a worker, you can be paid either for a piece of work or for the time you work. With factory production, it became more common for work and time to be linked together. It then became important that working hours were as efficient as possible. Time studies investigated how the work could be done faster and with less energy consumption by both the machines and the workers.

Model of the tanker M/T "Strix"

Before World War I, petroleum was primarily a light source. During the war it became an energy source with many more uses. Norwegian shipowners invested in tankers, and in 1930, when "Strix" was built, Norway had the world's third largest tanker fleet. Growth has continued. Today, 27 times more oil is transported by ship than in 1935, and roughly a quarter of all ship transport is oil freight.

Front tire on T/T "1978

The oil tankers are not only workplaces, but also places to live. Those who sailed in Asia had the longest time out, who were often out for two to three years at a time before the Second World War. Sailing times have gradually been reduced. On board, the crew mainly works with operation and maintenance. With iron and steel ships, it is primarily about the fight against rust.

7. Fossil Adventures

Norway is an oil state. Large revenues come from the extraction of oil and gas, and Norway has an extensive industry linked to production. In the autumn of 1969, Ekofisk was discovered. It was the start of the business in the North Sea. But Norway was also part of other oil adventures. Industrial extraction of oil began in the latter half of the 19th century with fields in the USA, Romania and Azerbaijan, among others. Norwegian engineers and businessmen helped to retrieve the oil and Norwegian shipowners and sailors transported it from the fields to the consumers.

Beyond the 20th century, the world – and Norway – was reshaped by oil. It formed the basis for, among other things, the large urban development of Drabant, which reshaped the landscape and lifestyle. The car opened the way to living longer from work and a more fast-paced leisure time. Throughout the 20th century, increased supply of oil has gone hand in hand with increased prosperity. Norway has been a happy oil country - especially when oil prices have been high. Now the burning of fossil fuels fills the atmosphere with more and more greenhouse gases. Once it ends. Is it still an adventure?

The Ekofisk tank

Cast in concrete, with a height of over 70 metres, the Ekofisk tank could store up to 1,000,000 barrels of oil. It was built as a storage site for oil from the Ekofisk field, but was quickly replaced by a pipeline to Teesside in England. The tank is no longer in use.

"Soon it will be over. Not next year, not in ten or twenty years, but soon. From the sea's perspective, it is soon. When the helicopter takes off, I see everything quite clearly.

When each and every drilling platform has emptied the 15-30 wells below them, when they have filled the entire reservoir with water, then they will lift the platforms away, one by one. Only the concrete giant will stand here, in the middle of everything,

but slowly surely it will sink into the sea and be lost.”

Marit Eikemo, "Everything sinks into the sea", Samtidsruinar (2009)

Baku, Azerbaijan

From the 1870s, the large oil fields around Baku were industrialized. In 1872, the Swedish Nobel family founded the oil company Branobel. It was for a time Russia's largest company and spread throughout the kingdom through oil wells, pipelines, refineries, tankers, railways and a multinational workforce. The revenues from the oil in Baku accrued mainly to European investors

Villa Otium

In 1911, Hans Olsen and his family moved into Oslo's largest and finest private residence designed by Henrik Bull. The villa and garden were reminiscent of the Russian palace villas the family had lived in St. Petersburg and Baku, where Hans Olsen managed the Nobel family's oil company Branobel. The villa is today the residence of the American ambassador to Norway.

Oil wells in Baku, Lumiere Brothers 1897.

Over 200 refineries were in operation around Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. They spewed thick, black oil smoke. The pollution was great, the working conditions bad and the class differences huge. At the beginning of the 20th century, the political and ethnic conflicts grew. The oil workers went on strike, and Baku's oil industry became a hotbed of revolutionary activism led by, among others

In Æventyrland: Experienced and dreamed in the Caucasus

In 1899, Knut and Bergljot Hamsun traveled from St.Petersburg to the oil fields in Baku. I Æventyrland describes their journey in a mixture of actual experiences, dreams and fiction. The oil is a companion on the journey – from burning kerosene lamps in front of Russian icons in St.Petersburg, as motive power for the locomotive on the Trans-Siberian railway and as a sensual, all-encompassing experience in Baku.

Light switch

The light switch was installed in Villa Parafina in 1901 and was in use until around 1930. In 1896 the State had bought the property built by the paraffin importer Fredrik Sundt. The villa was used as the prime minister's residence, before in 1908 it became the residence of the foreign minister. Since 1962, "Villa Parafina" has been the State's representative residence, while the Prime Minister lives in the neighboring property.

Parkveien 45, "Villa Parafina"

The villa was built in 1877 for Fredrik Sundt who was one of the largest importers of kerosene. Sailing ships brought barrels of petroleum from the USA and Scottish kerosene which were sold directly to customers in Oslo or distributed further in the country. Demand, prices and profits were high. His stately villa was quickly nicknamed Villa Parafina.

Statoil's headquarters

On 14 July 1972, the Storting approved the establishment of a state-owned Norwegian oil company that would look after the state's business interests on the Norwegian continental shelf. The following year, the company was named Statoil. In the mid-1980s, Staoil had become the largest operator in the North Sea, and in the 1990s the company entered into an alliance with, among others, BP and became an international oil company.

"Oil money for the good of all"

On 30 March 2011, Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg presented the action rule, which indicates how much of the income from oil operations can be used. He compared the forest and oil money; "we do as in good forest management: we only cut the growth." The oil fund was established in 1990 to ensure long-term sustainability in the use of oil money.

Drill bit

150 million years ago, algae and plankton sank to the bottom of the sea. Thousands of layers of new deposits, clay, sand and lime pressed them together and downward in the heat. At about 2,000 meters and 200 degrees, they turned into oil and gas. Like oil and gas, they slid upward again into a barrier of dense rock until a drill bit made a hole and relieved the pressure.

The Alexander Kielland accident

On 27 March 1980, one of the five legs of the Alexander Kielland housing platform was torn off in high seas on the Ekofisk field in the North Sea. The platform overturned. 123 perished, and 89 were saved. The accident is the biggest industrial accident in Norway. In total, at least 266 people have died at sea in Norwegian oil operations since 1967.

Traffic across Rådhusplassen

With the car came new, fast vehicles that required space. The predecessors had to get out of the streets and onto the pavement. At Rådhusplassen in Oslo, the port, the railway and the cars met. The idea of a tunnel under Akershus fortress was first launched in 1916 and in 1990 the Fortress Tunnel opened. The tunnel carries through traffic along the sea side of Oslo underground.

Tax stamp, 1932

Between 1927 and 1932, all cars had to have tax stamps to show that the year's inspection and road taxes had been paid. The color of the badge changed from year to year. Fees related to use were also gradually introduced. In 1931, a petrol tax of 3 øre per liter was introduced. A liter of petrol then cost around 20 øre. The fees were to cover expenses for maintenance and construction of roads.

Gargoyle Mobiloil Arctic

The pyramid-shaped oil can of 1 liter from Norsk Vacuum Oil was popular in the post-war period. The company imported and sold lubricating oils, especially to the fishing and merchant fleet. After the war, lubricating oils for vehicles became important. Lubricating oil protects moving parts in machines and engines, reduces friction and wear, water penetration and rust.

Fossil power

The importance of oil to modern warfare became clear during the First World War. Despite the fact that oil has been used as a fuel and light source in the Middle East since time immemorial, it was only now that Western oil companies took a serious interest in the oil deposits here. European and American companies wanted to secure resources for their home markets and to preserve a high profit on the oil they were already producing in the USA, Poland, Ukraine and Russia. The companies received military and political support from their country's authorities to secure control over the most important oil deposits in the world.

The income from the oil fields in the Middle East mainly accrued to the western oil companies, and only a tiny part went to the producing countries. Only with the nationalization of the oil industry in the 1970s did countries such as Iran, Iraq and Saudi Arabia receive a larger share of the income. Over 30% of the oil the world consumes today is produced in the Middle East, and this is where the largest reserves are located.

Beyond the 20th century, the world – and Norway – was reshaped by oil. It formed the basis for, among other things, the large urban development of Drabant, which reshaped the landscape and lifestyle. The car opened the way to living longer from work and a more fast-paced leisure time. Throughout the 20th century, increased supply of oil has gone hand in hand with increased prosperity. Norway has been a happy oil country - especially when oil prices have been high. Now the burning of fossil fuels fills the atmosphere with more and more greenhouse gases. Once it ends. Is it still an adventure?

Petrol pump from British Petroleum

After the Second World War, BP was one of the major distributors of oil products in Norway. With more cars on the roads also came more petrol stations. The fuel was stored in large underground tanks. The petrol pumps brought it up and over into the car's tank.

Fram fills oil at Vallø, 1910

Vallø Oil Refinery was founded in 1900 and was Norway's only refinery until 1960. The refinery made products such as transformer oil for power stations, fuel for motor boats and vehicles and lubricating oils for machines. Polarskuta Fram used a number of different energy sources on its expeditions. In addition to sails, a coal-fired steam engine, kerosene and a wind turbine with batteries, in October 1910 the schooner was also allowed to fill the stores with oil.

Refinery at Mongstad, 1975

Oil is not just oil. The chemical composition varies from oil field to oil field, and before it can be used it must be refined through refining. The refinery at Mongstad was built by Norsk Brændselolje and Norsk Hydro and was completed in 1975. With crude oil from the Middle East and the North Sea, the facility produced a number of products.

Magnetic card from Norol

Norol was founded in 1976 as a state-owned Norwegian distribution company for petroleum products. The company took over from Norsk Brændselolje, which had been owned by, among others, BP. In 1988, the company was taken over by Statoil. Statoil then became a so-called integrated oil company that did everything from exploration, extraction and production of oil to the sale of petrol (and sausages).

Oil storage in Abadan, Iran

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) was founded in 1909 to exploit oil fields in Iran. The company was established at the request of the British Ministry of the Navy. The British government owned 51% of the shares from 1914. The company changed its name to British Petroleum (BP) in 1954.

The oil coup of 1953

In 1951, Iranian Prime Minister Muhammad Mosaddeq nationalized the country's oil industry. Production and distribution had been controlled by Great Britain through the company APOC, later BP, and the main part of the income taken out of the country. In 1953, the United States and Great Britain supported a coup to depose Mosaddeq. From 1954, Iran's oil industry was again controlled by Western oil companies.

Map of pipelines, oil terminals and oil fields in the Middle East

The oil is transported out of the oil fields via pipelines. They go to refineries in the Persian Gulf or north to the Mediterranean, where the oil is pumped into large tankers. The ships carry the oil on to customers all over the world.

Bomb

This cement bomb was acquired by the Army Air Forces in 1914. Grenades had been dropped from aircraft during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911. During the Mexican Civil War in 1913, an aircraft built to carry bombs was used for the first time.

"Jerry can", 1942

The petrol can was developed in Germany in the interwar period. The jugs were important for the motorization of the military arms, and enabled rapid movements. They were easy to stack, not particularly heavy and easy to manufacture. From 1939 it was copied by the British, Americans and eventually also in

Plane propellor

In 1903, the American Wright brothers made the first flight with a motorized aircraft. In the beginning, military flight was practically dominant, but after the First World War airplanes were used for sports, exploration and surveying, for the transport of goods, mail and passengers in addition to warfare. This propeller was purchased for a smaller aircraft around 1920.

Magazine for Colt machine gun for aircraft

During the First World War, the machine gun was mounted on aircraft, and thus the fighter plane was invented. Propelled by gasoline-powered internal combustion engines, aircraft became a decisive force of war. Britain entered the war in 1914 with 11 trained military pilots, and by the end of the war had more than 20,000 aircraft of various types, 100 airships and nearly 300,000 enlisted men.

Model of the container ship "Bayard"

The container ship "Bayard" was built for the shipping company Fred. Olsen at the Ankerløkken shipyard in Florø in 1974. The container system was developed in the USA in the 1950s and dramatically reduced the costs of transporting goods. About 90% of all goods we buy have once been in a container.

Container ship "Moscow"

With the container ship, shipping goods over long distances became cheap. It is more profitable to produce goods where wages are low and transport them to consumers far away than to have factories close to the market. Gradually the ships have grown bigger and bigger, so big that the Panama Canal has become too small. Will the ships get even bigger when the ice melts in the north?

United Coal Importers in Bjørvika, Oslo harbour

The container ships changed the port areas. Before the containers, the harbors were the core of the city. Unloading, loading and storing containers requires a lot of space, and the ships disappeared from the center to the outskirts of the city.

Sleipner petroleum engine