Organization Todt and forced labor in Norway 1940 – 1945

OT in Norway

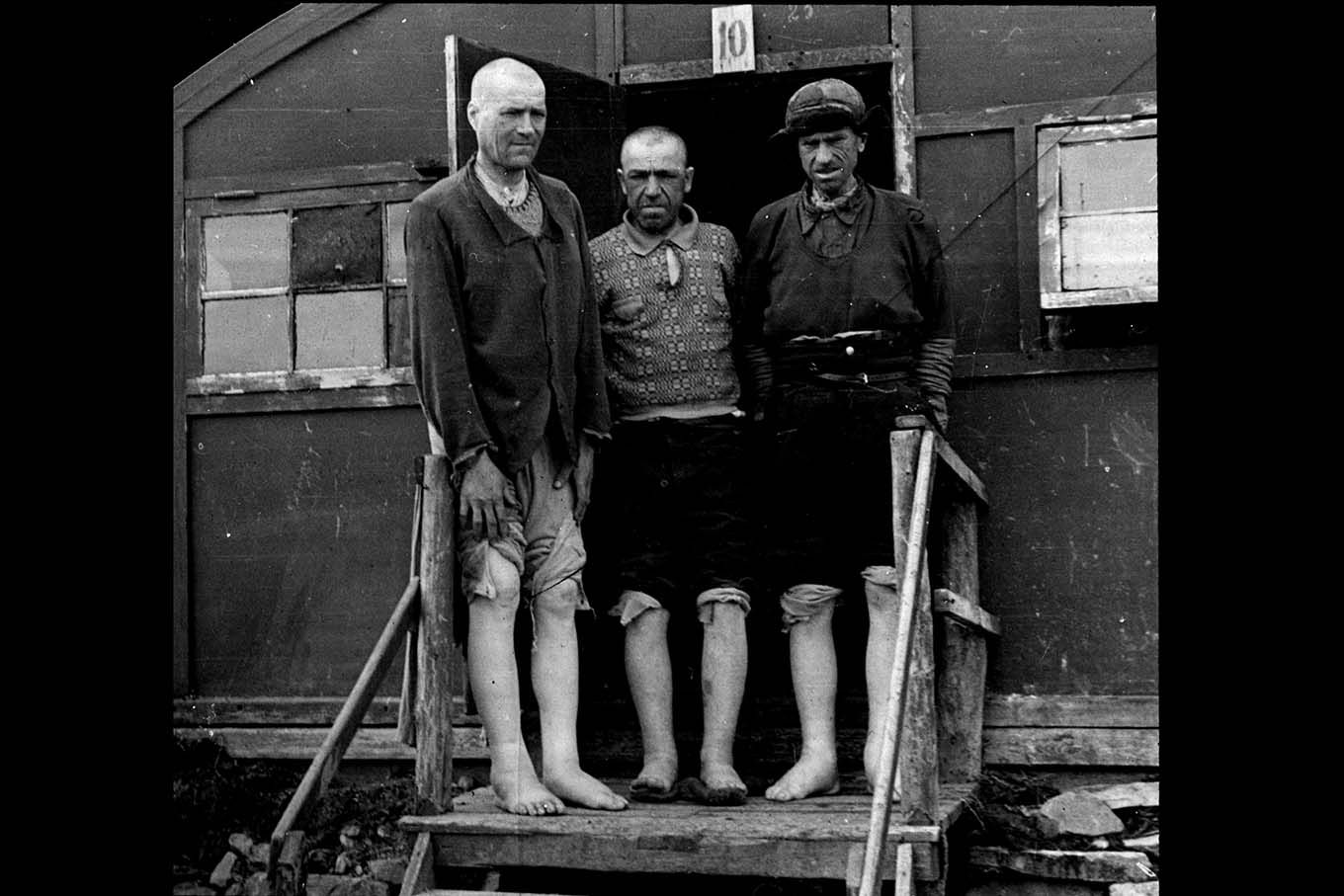

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

The prisoners formed the backbone of OT's workforce. Soviet prisoners of war were in the superior majority, but the OT also exploited the labor of civilian prisoners – both political prisoners and prisoners convicted of criminal offences. Towards the end of the war, over 50,000 prisoners worked for Einsatzgruppe Wiking.

"Norway is the destiny zone of the war"

Towards the end of 1941, it was clear that Germany's "lightning war" in the East had failed and that the war would drag on. In order to secure German supply lines to the Murmansk front, Hitler had already in October 1941 ordered the construction of a railway north through Finland. However, Todt was skeptical, and the plans were shelved. A little later, Josef Terboven, the German High Commissioner in Norway, suggested that the connections to the north could instead be secured over Norwegian territory. In addition to completing National Highway 50 up to Kirkenes, today's E6, 1,200 kilometers of new railway line, the so-called polar railway, was to be built along the same route. The road and rail projects were to eliminate ship transport along the coast, which was vulnerable to torpedoes.

In Berlin, the fear of an Allied landing in Norway grew. In January 1942, Hitler stated that Norway had become the "zone of war's fate" and demanded the forced development of the Norwegian coastal defences. Numerous coastal forts and a series of heavy batteries - later referred to as Festung Norwegen - were to be built and incorporated into the gigantic Atlantic rampart that was under construction from Biscay to Kirkenes.

In parallel with the plans taking shape, a tug of war took place over who would be responsible for the building assignments. Fritz Todt's negative attitude towards the polar railway probably contributed to OT initially keeping a low profile in Norway. Only after Todt's death in February 1942 was it decided that OT, now with Speer at the head, should establish a separate department in Norway.

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

Einsatzgruppe Wiking

In April 1942, OT established a division in Norway under the name Einsatzgruppe Wiking. The department was at one and the same time subordinate to National Commissioner Josef Terboven in Oslo and OT chief and armaments minister Albert Speer in Berlin. It was Hitler himself who decided which projects should be prioritized. At its peak, the OT in Norway controlled a workforce of around 90,000 men and over half were Soviet prisoners of war. During the war, Einsatzgruppe Wiking became the country's largest builder with great influence over the distribution of building materials and other economic input factors.

The head office of Einsatzgruppe Wiking was located in Oslo and administered a number of construction offices around the country which in turn oversaw the local construction sites. At the head office, there were separate staffs responsible for the construction of roads, railways, fortifications, etc. The key personnel were engineers and architects with a high academic education.

Einsatzgruppe Wiking also had Denmark as its area of responsibility. Einsatzgruppe Wiking built on the contact that had already been established between Todt, Speer and Terboven. In collaboration with Terboven, Todt had since autumn 1940 planned the construction of the Reichsautobahn between Halden and Trondheim. Speer was the chief architect for Neu Drontheim, the new town to be built southwest of Trondheim. Todt was also involved in this work. OT's first regular assignment in Norway was the construction of the submarine bunker Dora in Trondheim. The work started in the spring of 1941 and was led directly from Berlin until the creation of Einsatzgruppe Wiking.

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

Hitler's "Viking Order"

The construction program for Einsatzgruppe Wiking was determined by Hitler in a so-called Führer directive from May 1942. In addition to major road and railway projects, OT was to build coastal forts, coastal batteries, submarine bunkers and factories for the production of light metal with associated power plants. The projects were described by Hitler as "decisive for the outcome of the war" and were to be carried out in the shortest possible time. The Führer directive was issued to Minister of Armaments Albert Speer and strengthened OT's position vis-à-vis other German actors, who carried out construction activities in Norway, primarily the Wehrmacht.

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

The workforce

OT's workforce in Norway consisted of two main categories: prisoners and civilian forced labourers. Most of the civilian workers were what we would call forced laborers today - they were recruited by means of coercion and had limited influence over their working situation. Although some started their careers in OT more or less voluntarily, they nevertheless quickly ended up as forced labourers, as OT rarely allowed anyone to quit. After the contract period had expired, it was common for OT to extend the contracts without obtaining consent from those concerned. The civilian forced laborers were entitled to wages and were granted certain social rights. The treatment varied based on the workers' national and ethnic affiliation.

The prisoners formed the backbone of OT's workforce. Soviet prisoners of war were in the superior majority, but the OT also exploited the labor of civilian prisoners – both political prisoners and prisoners convicted of criminal offences. Towards the end of the war, over 50,000 prisoners worked for Einsatzgruppe Wiking.

Photo: Riksarkivet PA 0276, Leiv Kreyberg's archive, photographer: unknown

The prisoners are coming

The large construction projects that were underway in 1942 required a massive effort of labour. In Norway, there were no idle hands, and from the very beginning it was clear that the projects depended on foreign prisoners of war and forced labour. Before the work could be started, extensive preparations were required. The prisoners were to be accommodated in camps, wood had to be procured for barracks, barbed wire for fences, searchlights for watchtowers, kitchen equipment, mattresses and tools of all kinds. For Norwegian business, there was good money to be made by assisting the Germans in these preparations.

Initially, it was the Rikskommissariat that was given responsibility for the preparations, but in March 1942 Hitler decided that the task should instead be given to the OT. 6,000 German skilled workers and 10-15,000 Soviet prisoners of war were immediately made available. The transfer of prisoners to Norway took much longer than anticipated, and only from 1943 did they form the dominant category in the OT's workforce.

Formally, OT had limited responsibility for the prisoners. While the prisoners of war were sorted under the Wehrmacht, which provided accommodation, meals and guarding, the SS was often responsible for political prisoners. Among the prisoners in OT's custody, only the Yugoslavs, primarily Serbs, were subject to the SS. They were treated in a particularly brutal and ruthless manner.

"Prisoners of war must be accommodated in buildings or barracks that provide every possible guarantee for health and well-being." Excerpt from the Geneva Convention of 1929, paragraph 10

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

Grossraumtechnik – Hitler's Polar Railway

Towards the end of 1941, Hitler decided that a "polar railway" should be built north, through Norway, from Mo i Rana to Kirkenes. Measured in terms of the efforts of prisoners of war, the polar railway was OT's biggest project in Norway. The line was supposed to secure German supply lines to the Murmansk front and help ensure that iron ore and nickel could be transported south to Germany. Although the track was justified on the basis of immediate utility, there was no doubt that construction would take a long time. Strictly speaking, the project only made sense in a longer perspective; it belonged in Hitler's fabulation about the coming Grossraum. If the polar railway was connected to the existing Murmansk railway, it opened up a continuous connection between Oslo and Saint Petersburg.

The Polar Railway can be seen as an expression of the Third Reich's "space policy". Hitler made the OT a tool for this policy. Effective organization and the use of modern technology would make it possible to overcome the lack of time and resources.

"For us as construction people, the completion of the railway to Narvik is a technical honor of the highest class. No one should be able to accuse us of not having used the necessary energy and also rejoiced in this magnificent technical work.” Quote: Speer, in a letter to Willi Henne, November 1944

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

Civilian forced laborers from 21 nations

Civilian workers, from a total of 21 nations, were mobilized to work for OT in Norway. The vast majority of these were what we would call forced laborers today, as they were recruited under duress. The majority of these received a salary and were initially entitled to certain social benefits such as holidays and leave. Many of them were associated with private German firms, which were engaged by Einsatzgruppe Wiking.

The treatment of the civilian forced laborers varied based on their national and ethnic affiliation. The civilian forced laborers from the Soviet Union were worst off.

Norwegians were also forcibly discharged, authorized by German regulations. This was organized and carried out by the Norwegian administration. During the war, around 30,000 Norwegians were forcibly conscripted into Einsatzgruppe Wiking. Many failed to show up for service, and Norwegians in OT's service never exceeded around 20,000.

"The eastern workers are in a special position [...] They can and must be handled much more harshly than the culturally superior people from the Czech Republic and Western Europe." Responsible for manpower issues in OT, Max Erich Feuchtinger, 1944.

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

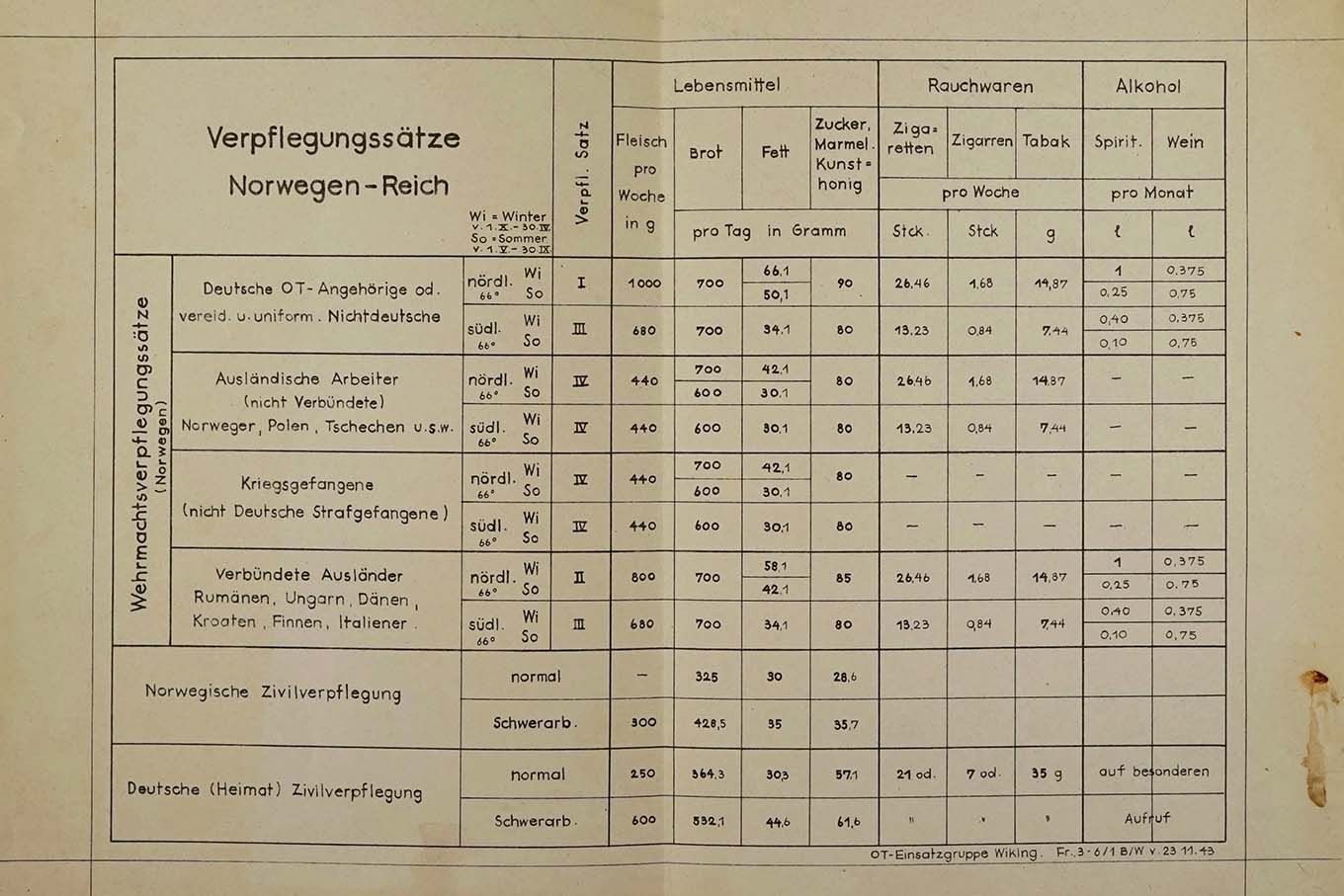

The scarce food

German OT workers had the best access to food. Initially, workers from countries that were Germany's allies were supposed to have similar rations, but as a rule they received far less. Workers from occupied countries, such as Norway, had to make do with even lower rations. In general, workers from Eastern Europe ate less and worse than workers from countries in the West. That you actually got what you were promised was not a given. The rations were adapted to local conditions. Bread was often supplemented with cabbage and potatoes, meat was replaced by fish. The prisoners suffered the most from the lack of food. For the Serbian, German and Soviet prisoners who came to Norway in 1942, the supply situation was catastrophic. The leader of Einsatzgruppe Wiking, Willi Henne, took several initiatives intended to improve conditions.

In order to carry out its projects, OT depended on cooperation with private German and Norwegian construction companies. The companies were responsible for the actual construction, while OT organized the work, provided building materials, machines and extra labour. German companies were usually used as main contractors, but these often linked Norwegian subcontractors. There is little indication that Norwegian companies hesitated to participate in OT's projects. As a rule, the contracts were entered into voluntarily, on a purely commercial basis. The large road and rail projects also contributed to NSB and the Norwegian Road Administration working very closely with Einsatzgruppe Wiking.

For security reasons, initially only German actors, mainly private German construction companies, were given access to the prisoner workforce. While private Norwegian companies only occasionally worked with prisoners, the state institutions NSB and the Swedish Road Administration came closer to the prisoners. In the first place, this concerned the Swedish Road Administration, which at times had "employer responsibility" for several hundred prisoners of war.

The occupying power's demands and orders created difficult dilemmas for OT's Norwegian partners, but in retrospect it is reasonable to ask whether the Norwegian willingness to cooperate went too far.

"The Norwegian willingness to cooperate (...) made it possible for the occupying power to keep the economy going until the last days of the war." Hans Klaussen Korff, the National Commissioner's Office's financial management (p. 357).

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

"German work"

At the beginning of the war, there was good money to be made by taking work at German plants. Over 200,000 Norwegians were engaged in so-called German work, and the majority worked for the Wehrmacht. During the war, the economy was increasingly regulated. Measures to limit wage growth were implemented, while the ability to freely change jobs was severely curtailed.

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

The Norwegian Road Administration and the prisoners of war

Many of the Serbian prisoners, who came to Veganlag in Nordland in the summer of 1942, moved into camps built by the Road Administration. Not infrequently, the prisoners' work was monitored and controlled by engineers from the Norwegian Road Administration. In a report from February 1944, road director Andreas Baalsrud states that the Road Administration at Elsfjord-Korgen has 500 prisoners of war in its workforce. On the German side, the experience was nevertheless that it was unfavorable to let Norwegians work with prisoners, because the pace of work was higher when the prisoners worked for German construction companies.

In order to speed up the road projects, which the Germans gave high priority to, it happened that the Swedish Road Administration gave advice on how OT should deal with the forced dismissal of Norwegian workers.

"On the stretch of 12 km. further from Korgen, 80 Serbs are currently working under the auspices of the Norwegian Road Administration despite the winter weather" January 1944

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

NSB and the prisoners of war

Until the establishment of Einsatzgruppe Wiking in 1942, it was the Wehrmacht that led German railway construction in Norway. In the south, the aim was to complete the connection between Oslo and Stavanger. In the north, the Nordlandsbanen was to be completed to Bodø. Without consulting the Wehrmacht, Hitler decided in December 1941 to increase his ambitions radically: Within two years, a "polar railway" was to be built all the way to Kirkenes. The construction was to take place under the auspices of OT. Despite the fact that the project was greatly scaled down and had Narvik as its end point, the polar railway came to employ over 22,0000 prisoners of war. Of these, at least 2,200 perished.

Otto Aubert, who headed NSB's construction department, initially opposed the use of prisoners. NSB was nevertheless required to investigate how a prisoner effort could be organised. The investigation took place in January 1942 and concluded that it would be possible to use prisoners on the Nordlandsbanen. However, there is no indication that NSB was any promoter of the use of prisoners. Aubert maintained throughout that OT would be best served by leaving all construction to NSB and its Norwegian workers.

The prisoners, who were interned at railway facilities in northern Norway, formally worked not for NSB, but for OT and the German construction companies.

Although the prisoners at the road and railway facilities in Northern Norway formally worked for OT and German construction companies, NSB and the Norwegian Public Roads Administration ended up in many situations with an operational responsibility for the prisoners. Often, the prisoners' work was monitored and controlled by employees of NSB and the Norwegian Road Administration. Documents show that the responsibilities were tangled in many places.

Ideologically motivated violence directed by civilians

The cooperation with the OT meant that ordinary civilian Germans got very close to the prisoners. Engineers and middle managers in German construction companies instructed the prisoners, supervised their work and were also given tasks related to guard duty. Violence against prisoners under the auspices of civilian Germans occurred. In this way, OT contributed to the Nazi regime being able to delegate responsibility for ideologically motivated violence to civilians and make them jointly responsible for the regime's crimes.

The architect Leif Egeberg acted as an intermediary between OT, the National Commissionerate and Norwegian business. Egeberg mediated assignments to Norwegian firms that were willing to build roads that were particularly important from a military strategic point of view. In order to realize the assignments, Egeberg collaborated closely with the Norwegian Road Administration. The Swedish Road Administration agreed to ensure the quality of the companies' work and lent out engineers for consulting assignments. The mix of roles makes it difficult to assess the responsibilities. Leif Egeberg was convicted of treason after the war.

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

Disgruntled workers

The German censorship in Norway intercepted numerous letters from disaffected OT workers of all nationalities. Review topics were poor food, long working days and non-payment of wages or holidays.

"Foreign workers, mainly Bulgarians and Romanians in the Einsatzgruppen Wiking have not received any salary transfers for over a year."

"According to the Danish workers, the corridor was full of bed bugs. Several Danes showed the bed bug bites on their bodies. Even OT people told me that the conditions in Oslo were catastrophic, but that nothing could be done about it."

"On the way back, the Danes were placed in an already full gymnasium at Grünerløkka school. According to the Danish workers [...] there was a barrel with a lid in a corner of the gymnasium; where those lodged during the night did what was necessary."

"The soup contained seaweed."

"Where I come from, even the pigs get better food than what we get here."

Table indicating food rations for different categories of OT workers. Photo: National Archives RAFA 2188