Organization Todt and forced labor in Norway 1940 – 1945

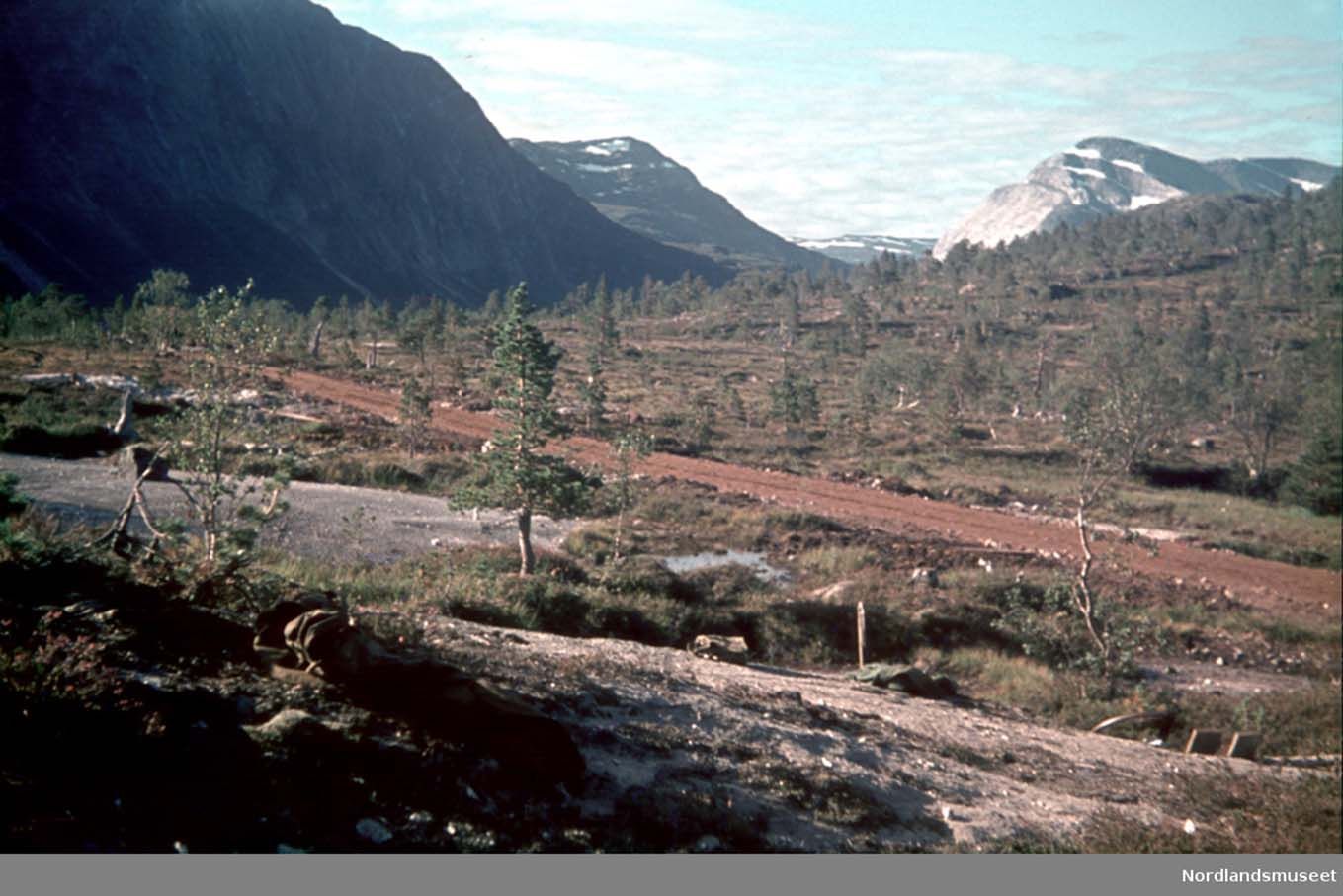

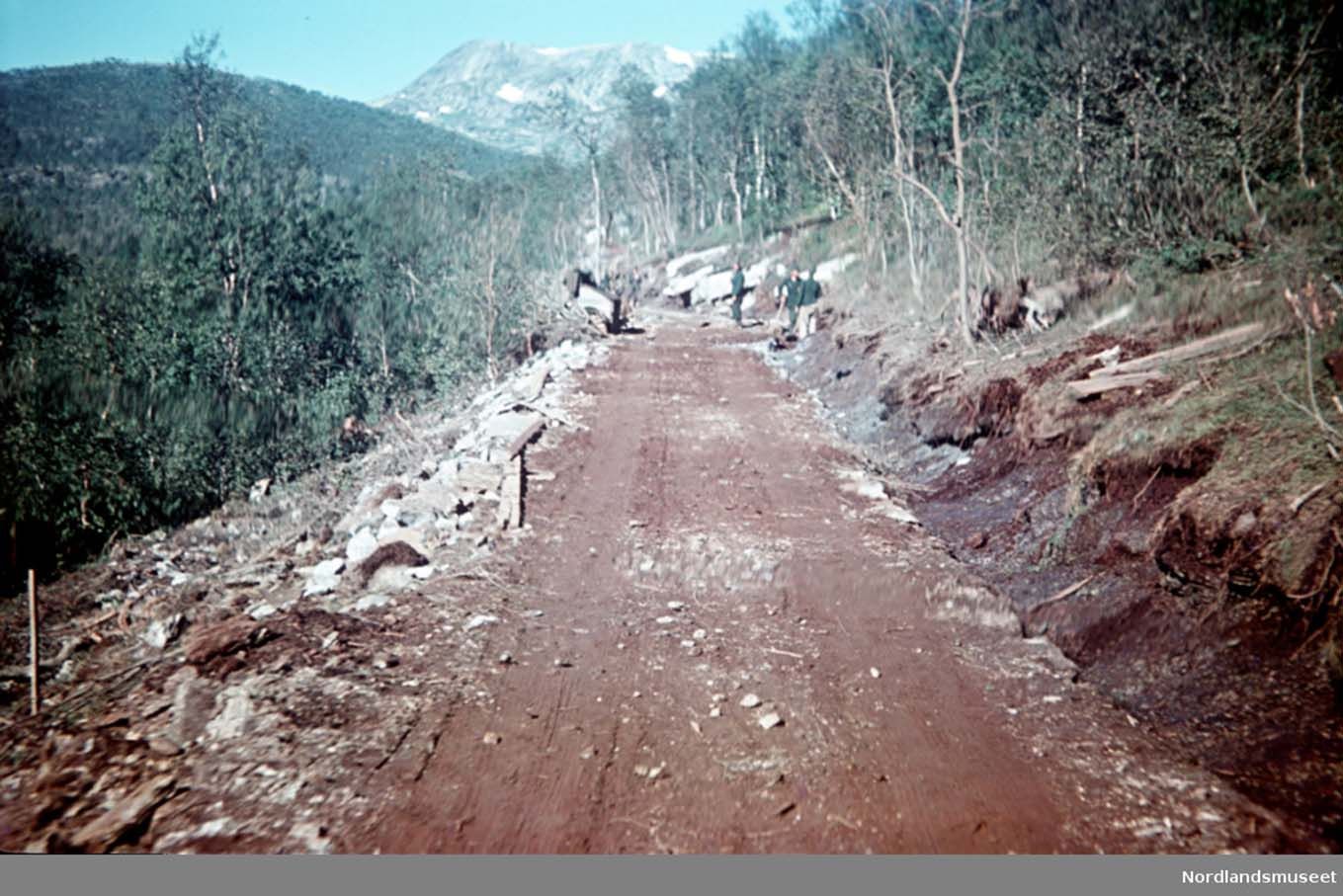

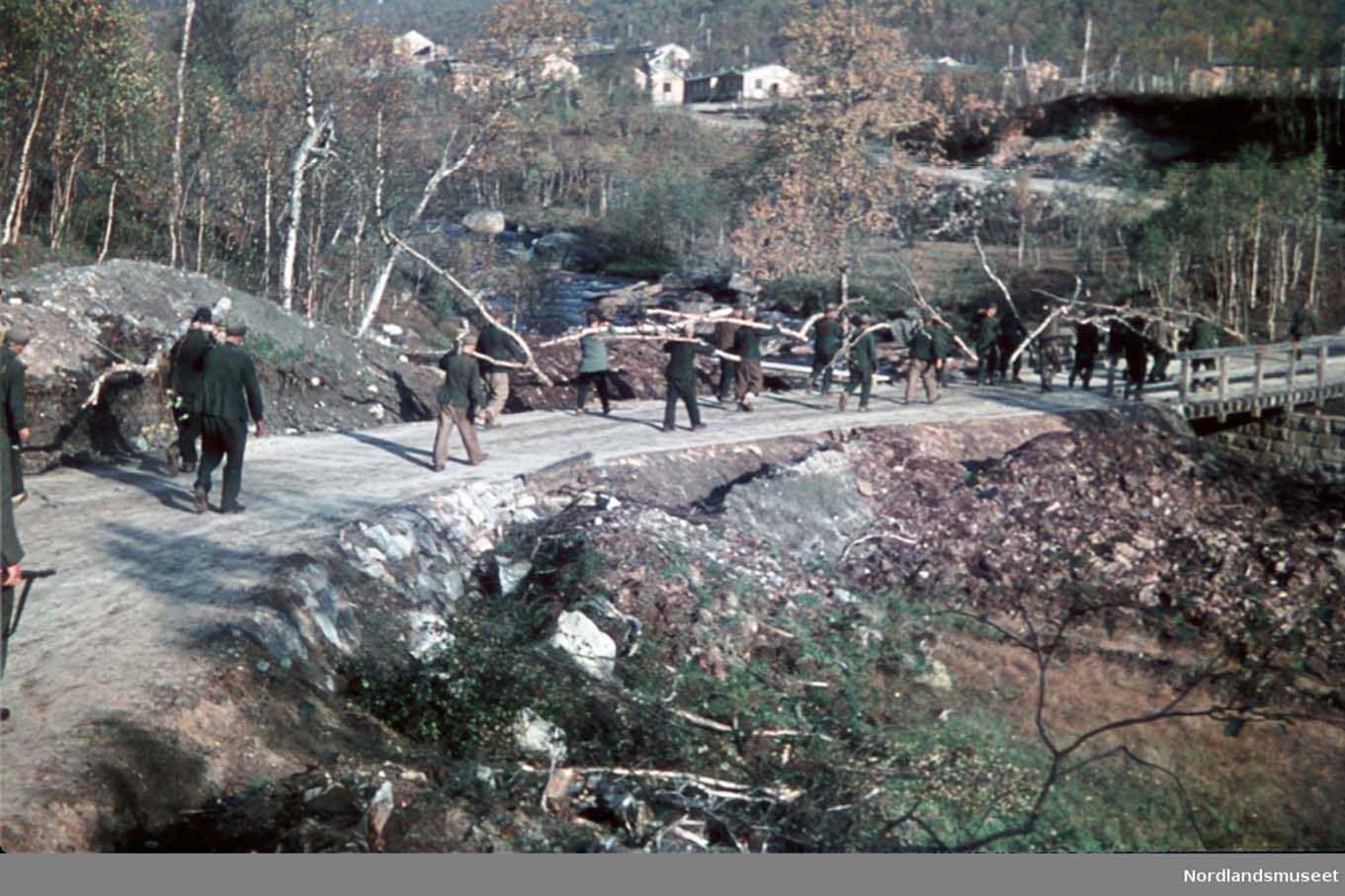

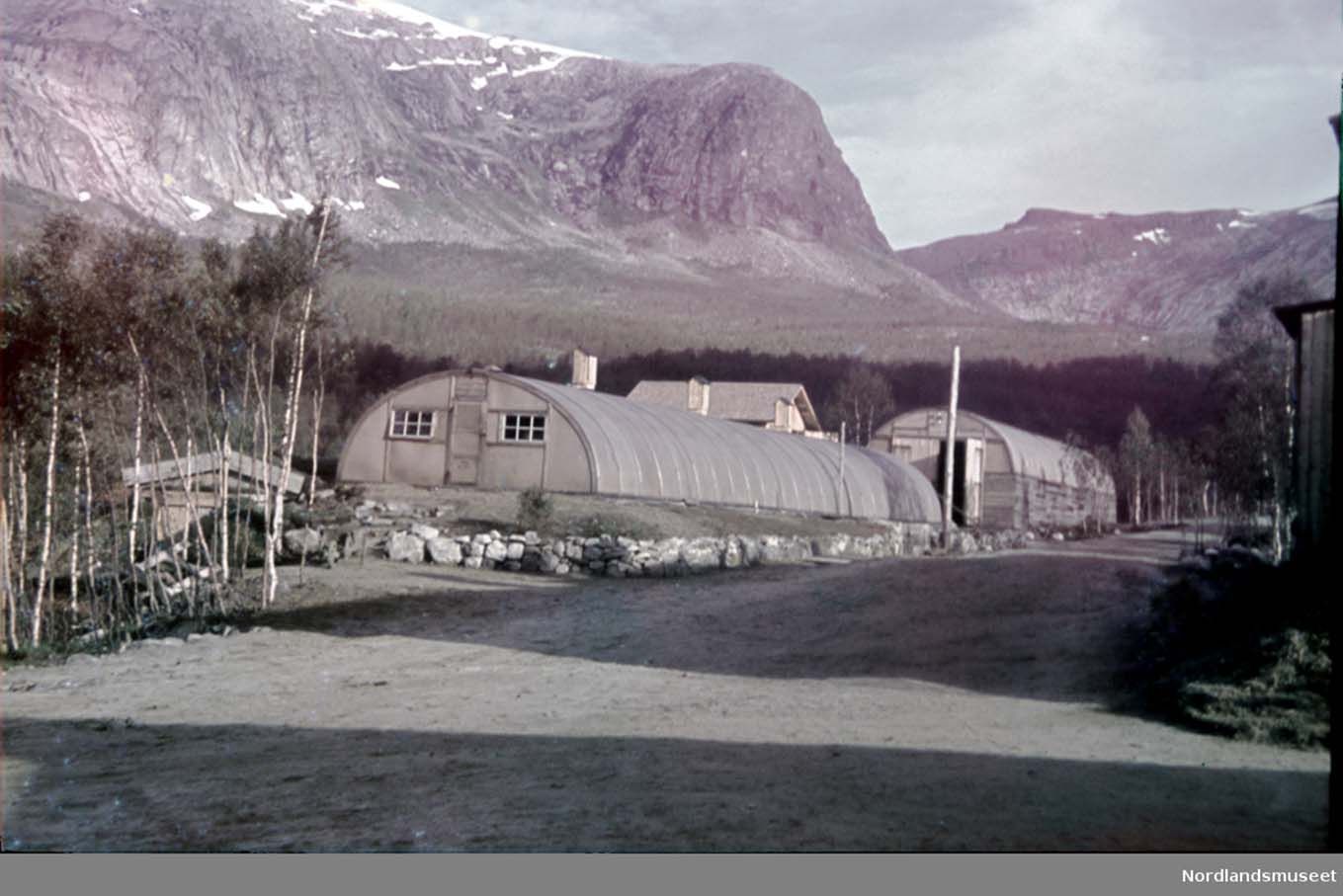

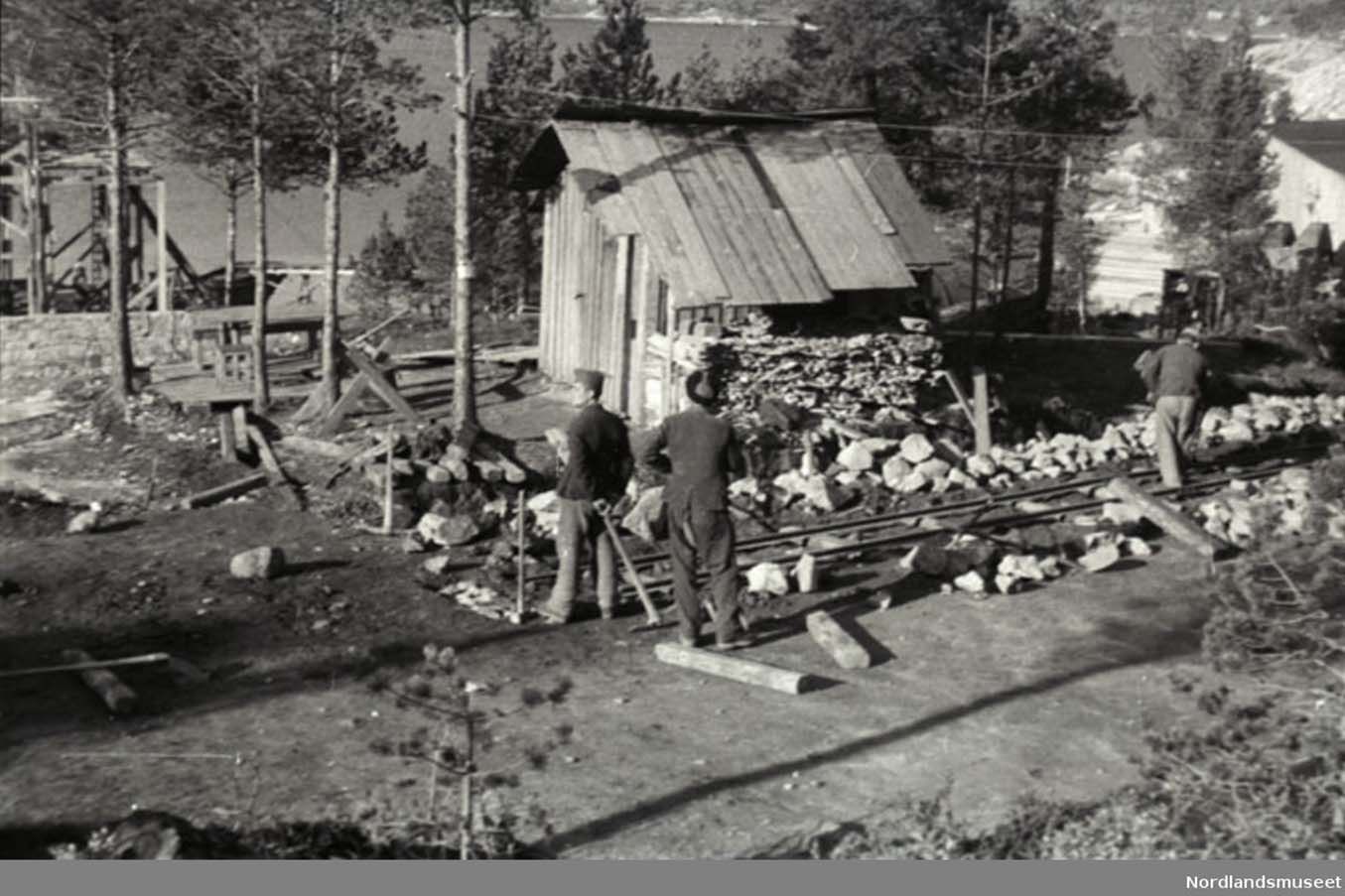

The Polar Railway

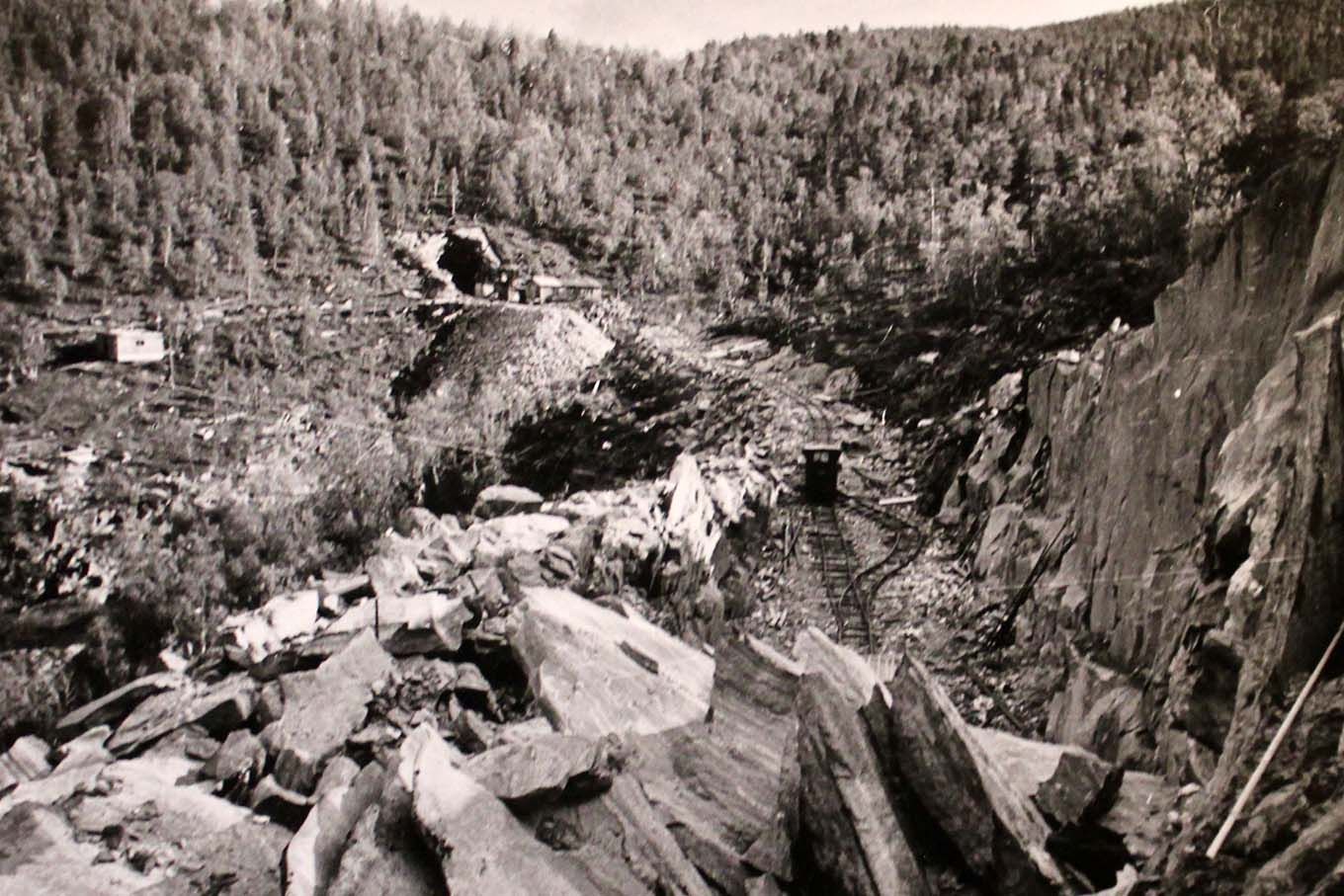

The construction of the Polar Railway continued until the last days of the war. Around 2,200 prisoners had died along the way

Photo: Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

By Ketil Gjølme Andersen

See Article 5 of 11 Historical journal03 / 2018 (Volume 97) where you can also click directly to the notes.

After the launch of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, Armaments Minister Fritz Todt visited the front several times where he could see for himself that the blitzkrieg had stopped. Ever since the attack on the Soviet Union began, the construction organization that bore his name, Organization Todt (OT), had been working feverishly to maintain the supply lines to the east. Todt was the Third Reich's foremost engineer.

Before the war, he had built the Autobahn and the fortifications against France, the so-called Western Wall. In the coming Nazi empire, infrastructure built by the OT would lay the foundation for control over large areas of land. Todt handled even the most complicated construction assignments, and for the Führer, OT appeared as proof that technology and efficient organization could work wonders. That is why Todt Hitler turned when he wanted to build a railway in Finland and Norway in the autumn of 1941. The Lapland army needed supplies, while the industry at home in Germany depended on raw materials from the northern regions. Only rail could replace the attack-prone ship transport along the Norwegian coast. By the end of 1941, Hitler had become convinced that a 1,200 kilometer extension of the Nordlandsbanen to Kirkenes would be decisive for the end of the war.

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

The idea of building what was subsequently referred to as the "Polar Railway" arose out of the acute military situation, but really made little sense in the short term. The project was so extensive that construction would necessarily take a long time. In order to understand why Hitler insisted until the end of the war that the track should be completed, it is necessary, as the historian Alan Milward has also emphasized, to include the Leader's long-term vision of the new order of Europe. The polar railway opened up the economic exploitation of the areas in the north and had staggering geopolitical potential. If it were connected with the existing Murmansk line, a continuous connection could be established all the way from Oslo to St. Petersburg.

For the German war economy, the project became a major burden. In retrospect, it appears as an example of Hitler's detailed management of the resource effort in the Third Reich. The project is also an example of the technological optimism which, according to several historians, characterized the Führer. For Hitler, the technique appeared to be driven by will. And when the technique was subject to the compelling force of the Führer's will, there were almost no limits to what results could be achieved. Hitler's voluntarism was fully demonstrated during the construction of the Polar Railway.

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

Fritz Todt himself was not among those who were eager to build a railway in Norway. His advice was to wait until the war was over. While the war was going on, the project would steal resources from other and more urgent tasks. Perhaps this contributed to the Polar Railway becoming part of OT's portfolio only after Todt's death in February 1942. In the following months, it was up to Todt's successor, Albert Speer, to organize the construction of the line. It happened within the framework of the new subdivision that OT established in Norway in the spring of 1942: Einsatzgruppe Wiking (EW).

Until the establishment of EW, the Wehrmacht had been responsible for German railway construction in Norway. In close collaboration with NSB, the Wehrmacht built railways in both the south and north of the country. After OT took over responsibility for the Polar Railway, NSB had to deal with a new partner. As part of its model for the implementation of the project, OT interned around 25,000 prisoners of war. How did NSB handle the collaboration with OT, to what extent did the company incur co-responsibility for the efforts of prisoners?

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

Historians Alan Millward, Robert Bohn, Marianne Neerland Soleim and Berit Nøkleby are among those who have made valuable contributions to the understanding of the Polar Railway. Nevertheless, more detailed representations are still missing. So far, Joachim Petersen's book Hitler's Polarisenbahn from 1992 is the most comprehensive. However, the book is based on limited source material and is characterized by a somewhat rambling presentation. The Polar Railway is also touched upon in recent studies by the historians Bjørn Westlie, Silje Thjømøe and Finn Rønnebu. All three profitably highlight the fate of the prisoners of war. While Rønnebu is most concerned with how Norwegian local communities adapted to German construction activities, Thjømøe and Westlie focus on NSB's role as the occupying power's partner. This article draws alternately on the aforementioned works, but challenges Westlie's analysis of the relationship between NSB, Wehrmacht and OT. Westlie portrays it as if NSB actively gave its approval to the use of prisoners of war on the railway facilities in the north. As will be argued below, throughout the war NSB came to recommend a work organization which meant that prisoners should not be used.

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

Wehrmacht and NSB: Northwards, but how far?

The sparsely developed communications in Norway represented a major challenge for the occupying power. Even before the guns fell silent, Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, the supreme German military commander in Norway, ordered extensive upgrading of the infrastructure. In 1940, the north/south main road, highway 50, maintained a usable standard only up to Mosjøen in Nordland county. The railway was even more poorly developed than the road network. At the time of the German invasion, NSB was in the process of extending the Nordlandsbanen to Mosjøen. By deploying German crews in the rush, the Wehrmacht ensured that the new section could be opened earlier than originally planned, on 7 July 1940. Falkenhorst shone a light on the opening, creating the impression of having tightened its grip on railway construction in Norway.10

That was only half the truth. Whoever was to build a railway in Norway was completely dependent on cooperation with the railway company of the Norwegian state, NSB. In order to ensure control over the daily train traffic, NSB's operations department was immediately placed under German management. However, the construction department, which was responsible for the development of new lines, was allowed to retain a more independent position. Falkenhorst created a separate railway command, Kommando der Eisenbahn (Kodeis), which was to ensure that new construction projects were carried out according to German priorities.11 Kodeis was staffed with military railway engineers, but was not a construction organisation. Thus, Kodeis was dependent on a collaboration with NSB's construction department, led by Otto Aubert.

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

The first plans that Falkenhorst drew up in the autumn of 1940 were very ambitious. In southern Norway, the Sørlandsbanen between Oslo and Stavanger was to be completed, in northern Norway the Nordlandsbanen was to be extended northwards from Mosjøen. Exactly how far it was relevant to build was an open question - both Narvik and Kirkenes were mentioned as relevant targets. On the Norwegian side, at this time there were plans to extend the Nordlandsbanen to Bodø. The plan and the associated cost framework had been approved by the Storting before the war, but the necessary funds had not yet been allocated.

Falkenhorst's high ambitions unsettled the civilian part of the occupation government. If the most far-reaching railway plans were realized, the result could easily be economic collapse, warned the Rikskommissariat's financial experts. Terboven eventually found out that a cap had been placed on the amount of money Wehrmach could dispose of in Norway. In this situation, Falkenhorst chose to concentrate resources in the south. The first priority was to complete the line between Oslo and Stavanger. With NSB as construction manager, 4,200 men worked on the line in the summer of 1941. To further increase the pace of development, private construction companies from both Norway and Germany were brought in. In NSB, people were used to having full control over their projects and strongly disliked the measure. According to Aubert, the results were best when NSB built on its own.

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

For NSB's Director General Waldemar Hoff, it was crucial that development in the north followed the Norwegian pre-war plans. In September 1941, this also became Falkenhorst's line in practice when he approved the route NSB had proposed to Bodø. Final building permission was later granted by the National Commissionerate. Falkenhorst obviously saw the benefits of a good relationship with his Norwegian partner. NSB was listened to both when it came to where it was to be built and how it was to be built. The experiences with German companies on the Sørlandsbanen were not good, and Falkenhorst was determined to leave the construction in both the south and the north to NSB alone.

In the state budget for 1941/42, only approx. NOK two million for work on the Nordlandsbanen. It was therefore in the cards that the pace could not be very high. At least on the Norwegian side, it was taken for granted that construction of the line to Bodø "would extend over a number of years". If Falkenhorst had ever had the ambition to build a railway to Kirkenes, he had now put it aside. The course was set for Bodø, and it went at a rather leisurely pace. Then something happened that turned the situation upside down.

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

Enter the field: Hitler and Todt

The first step towards the decision to build the Polar Railway was taken on 22 September 1941, when Hitler announced that a narrow-gauge railway would be built from Rovaniemi to Petsamo in Finland. The railway was supposed to secure supplies to the Murmansk front, and enabled nickel from Petsamo to be transported in the opposite direction to the armaments industry in Germany. The lack of a breakthrough on the eastern front lurked behind the order, which was also connected in another way to the situation in the east. In the months that had passed since the invasion, the Wehrmacht had taken hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war. In line with Hitler's orders, the prisoners were to be left to their own devices to starve to death. However, the need to utilize the labor of the prisoners quickly arose. As stated in the order from 22 September, the Petsamo Railway was to be built "through ruthless exploitation of Soviet prisoners of war". The assignment was given to Fritz Todt.

Todt investigated the matter personally and delivered his recommendations in the form of a five-page memorandum on 9 October. For Hitler this was depressing reading. Germany's leading engineer concluded that the track in Finland should not be built. Despite the fact that it was a smaller, narrow-gauge track, the project was so extensive that during the construction phase it would make accessibility in the area worse than it already was. However, the investigation reveals that at this time Hitler was also considering bringing supplies to the front across Norwegian territory. Specifically, there was talk of a narrow-gauge railway along national highway 50 from Alta, via Nyborg to Kirkenes. In the same way as the track in Finland, this was a measure designed to remedy the "immediate supply situation".

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

A third railway project was also mentioned in Todt's report. The Führer had revealed his intentions for a more extensive expansion of the railway network in Norway to his Minister of Armaments. The aim was to build a continuous line from "Trondheim, via Bodø to Narvik and from there on to Kirkenes–Petsamo". That at least Todt regarded this as a long-term project is clear from the report. The line towards the Arctic Ocean was to be realized only "in the period after the war".

Todt's memorandum contained hardly any technical and financial studies. Presumably he saw it as unnecessary. Building a railway in an inaccessible arctic high mountain terrain was complicated and resource-intensive, and should not have been started as long as the war lasted. Todt had been strengthened in his conclusion after inspecting the relevant areas from the air. During a meeting with Falkenhorst, Todt spoke categorically against the Føreren's railway projects: "I don't build mountain railways." Hitler apparently accepted this conclusion when he announced on 14 October that the Petsamo Railway had been shelved due to "unforeseen technical difficulties". It turned out, however, that the Führer's plans for Norway were still intact.

Todt was the man Hitler turned to when he needed a technical miracle. As a rule, expectations were met. Todt himself shared Føreren's optimism on behalf of technical development; the two had sat together many times and fantasized about how in the future motorways and railways would bind the Nazi Empire together. In the autumn of 1941, however, Todt began to doubt the Führer's judgement. In early November he visited the front, where he witnessed an almost complete breakdown of German supply lines. He saw poorly equipped German soldiers and endless lines of starving Soviet POWs barely able to do productive work. Constantly new examples convinced Todt that the campaign was poorly planned and moreover based on overly optimistic assessments of the resources Germany had at its disposal. Measured against its enemies, the country's resource base was limited. The longer the war lasted, the smaller the chances of victory. During a meeting with Hitler in Berlin on 29 November 1941, Todt bluntly declared that the war "could no longer be won".

Until his death a few months later, Todt worked purposefully to streamline the German armaments economy. The resources had to be channeled to where they were most needed. It did not include 1,200 kilometers of railway line to Kirkenes.

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

From Terboven to Einsatzgruppe Wiking

While the relationship between the Leader and his minister of armaments cooled, the German Reich Commissioner in Norway appeared in Berlin. Hungry for recognition from Hitler, Terboven made himself available with advice on railway construction. While a year earlier Terboven had fought against the Wehrmacht's railway plans, he now supported the idea of a railway to Kirkenes. Together with the engineers in the Rikskommissariat's technical department, Terboven had drawn up a proposal which meant that a continuous connection to Kirkenes should not be built in the first instance. In areas where the terrain was particularly demanding, you should not bet on trains, but road or ship. The proposal was constructive, and could potentially have simplified the project to a considerable extent. Nevertheless, it was not Terboven's business to orient Hitler to reality. Obviously to impress the Leader, he stated that the connection to Kirkenes could be completed in less than two years!

Already while Terboven was in Berlin, the discussion about who should be responsible for the project began. As immediate start-up was desired, it would have been natural to give the task to the Wehrmacht and NSB, who had already built railways in the north. However, Hitler wanted to keep the Wehrmacht away. The role of builder had to be reserved for a body directly subordinate to the Führer himself.

Initially, then, Hitler had turned to Todt with his railway visions, and it is not unlikely that Todt was the Polar Railway's preferred builder. Nevertheless, the project initially ended up with Terboven. Based on the sources, it is not easy to follow the decision-making process in detail, but the combination of Todt's skepticism and Terboven's strong desire to make the Führer ready is probably part of the explanation. At any rate, it is certain that Terboven, the moment he returned from Berlin, set heaven and earth in motion to prepare his technical department for the mission. Head of department Heinz Klein was already well underway with the work when Terboven was asked on 14 January 1942, in the form of a "Führer assignment", to start the construction of the Polar Railway.

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

Soviet prisoners of war were considered crucial to the success of the project. The Führer was anxious to bring the prisoners to Norway as quickly as possible, and had promised Terboven a larger number at his disposal. 60,000 was a number that circulated. It was intended that the first prisoners should be shipped in as early as February. In order for the prisoners to be put to work, barracks had to be built. Tools, machines and building materials were needed. Unlike the OT and the Wehrmacht, the Reichskommissariat had no experience with large construction projects, and it was not many weeks before Klein and his colleagues realized that they were in deep water.

A number of problems presented themselves. On 17 January 1942, a telegram arrived from the SS saying that it was not possible to bring Soviet prisoners of war to Norway within the agreed deadlines. At the same time, it was clear that many of the input factors needed could only be obtained from Germany. Here, however, they were subject to a quota, which meant that the deliveries first had to be cleared by the right authority. The right authority in this case was Fritz Todt, who by virtue of his position as Generalbevollmächtigter für die Regelung der Bauwirtschaft (GB Bau) oversaw the distribution of economic input factors. In the second week of February, Klein learned that the application to secure key deliveries to the Polar Railway had been flatly rejected. The National Commissionerate formally had no opportunity to apply for quotas, it said. However, Klein was informed that the real reason lay elsewhere, namely that Fritz Todt "had been fundamentally opposed" to the implementation of the project.

When this became known in Oslo, the OT leader had already been dead for four days. Todt had died on 8 February when the plane he was in exploded on the way home from a meeting at the Führer's headquarters in eastern Poland. There is no written record of the meeting between Hitler and Todt, but historians assume that Todt had once again brought up the poor prospects for a victory. At the same time, rumors immediately began to swirl that Todt had been the victim of an assassination attempt, that it was Hitler who had arranged for the removal of a troublesome critic. However, no evidence has ever been found that the plane crash was anything other than an accident.

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

Todt's death had significance both for the Polar Railway and OT's role in Norway. Only a few hours after the accident, Hitler summoned Albert Speer, who was also in the Führer's headquarters that day. Hitler asked Speer to take over all of Todt's positions - Minister of Armaments, OT leader, GB Bau, etc. Speer was on his way out of the room when the Leader addressed him once more: "One more thing, Herr Speer, I want you to build the railway for me in Norway as Terboven has proposed."

In the course of the next few weeks, it became clear that the project Hitler had imposed on his new minister was to be perceived as an order to OT to set course for Norway. Already when Speer and Hitler met the week after Todt's funeral, on 19 February, Speer presented a proposal for the reorganization of the OT which, among other things, entailed the creation of a separate subdivision in Norway, Einsatzgruppe Wiking (EW). Hitler approved the proposal and recalled how "urgently important" the railway project was. To lead the task force in Norway, Speer appointed his most competent man, number three in the hierarchy after himself, the 35-year-old engineer Willi Henne.

The Polar Railway was the driving force behind the development that brought OT to Norway. More or less as an emergency solution, Hitler had first made Terboven the builder. After Todt's death, the project was immediately transferred to the new super minister, Albert Speer. As a representative of what should now really be called Organization Speer, Henne started his work in Norway on 1 April 1942. In addition to leading EW, he took over the position as head of the Rikskommissariat's technical department. In addition, he represented Speer in the position of GB Bau. Together, this made Her perhaps the most powerful person in the Norwegian war economy.

The construction program for the EW was finally laid down in Hitler's so-called Viking order from May 1942. Compared to the pilot order from January, the order was considerably more extensive; in addition to railways, coastal fortifications, roads, airports etc. were also to be built. EW ended up using most of its resources on fortress construction, but there is no doubt that the Polar Railway was technically and logistically the organization's most demanding single project in this country. Nor were any other projects planned with a greater effort by prisoners of war.

Nordlandsmuseet, photographer: Johannes Martin Hennig

NSB and the Polar Railway: With or without prisoners?

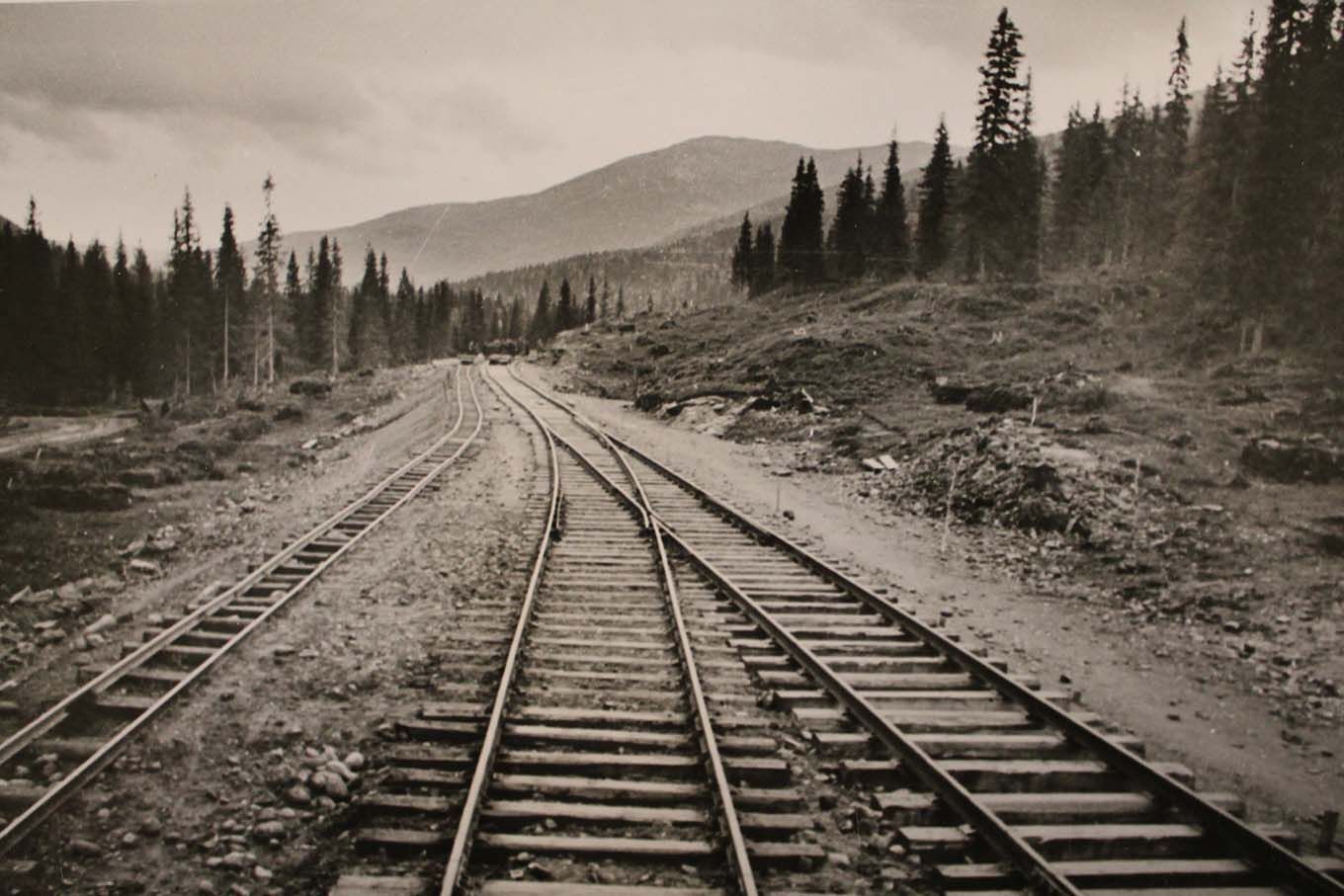

The play around the Polar Railway, which thus started with Terboven being given responsibility for the line, disrupted the established cooperation in the railway sector. No sooner had NSB and the Wehrmacht agreed to build to Bodø than the news came that Kirkenes was the new terminus. Falkenhorst was kept out of the decisions. "I was not at all consulted on the matter," he later stated.

In line with the established terminology, both Norwegians and Germans throughout the war continued to refer to the section between Mo i Rana and Fauske as the Nordlandsbanen. The name Polarjernbanen is often used for the section north of Fauske. The use of the term is a bit unfortunate because it covers up that the stretch Mo–Fauske, at the moment the extension to Kirkenes was decided, was incorporated into the Polar Railway and subject to its logic. For Hitler, the Polar Railway started in Mo. In what follows, we therefore have to deal with the fact that the section Mo–Fauske belonged to both the Nordlandsbanen and the Polarjernbanen.

Photo: Riksarkivet, RAFA3309_68, photographer: Pieper

The fact that the Nordlandsbanen had been subject to the logic of the Polar Railway meant that the demand for speed was given priority over consideration of costs. What this meant, the Wehrmacht and NSB realized already in December 1941 when it became known that the section up to Fauske had to be completed by October 1943. This was far sooner than planned, and to discuss how the work could be accelerated, NSB was called to a crisis meeting with Kodeis 29 December 1941.

The pace obviously depended on how large the manpower was deployed, and NSB was now asked to investigate various scenarios. It quickly became clear that NSB could no longer count on being responsible for the construction alone. Kodeis demanded that NSB, with immediate effect, associate Norwegian contractors as subcontractors. Presumably it was only a matter of time before German companies also appeared. In Kodeis, they also wanted an answer to "to what extent prisoners of war could be interned" on the stretch between Mo i Rana and Fauske.

Seen in isolation, it is not certain that NSB was so opposed to an increased rate of development. But the "forcing" that the Germans proposed was perceived as unjustifiable, and also meant that Norwegian pre-war plans were deviated from. As NSB learned from Falkenhorst, it was now out of the question to build to Bodø, all efforts were to be put into reaching Fauske as quickly as possible. After investigating the case, NSB forwarded its views to Kodeis in a letter dated 20 January 1942. The pace that was demanded entailed great risk, the letter said. Among other things, it would be necessary to raise capital in a completely different order of magnitude than before. While in 1941/42 it had been planned to use approx. NOK two million, NSB's estimate showed that the construction in 1942 alone would cost between NOK 50 and 60 million. All in all, the uncertainty was so great that NSB "could not promise that it would be possible to meet the deadline to reach Fauske by October 1943." Falkenhorst realized that the situation was unclear. In order not to lose time, he issued a guarantee of NOK 3.4 million in early January, which was to cover NSB's immediate capital needs. He hoped it would last until a final financing plan was put in place on the German side for the line to Kirkenes "as the Leader had requested".

Photo: Riksarkivet, RAFA-3309_U71, photographer: unknown

The question of putting prisoners of war to work on Norwegian railway facilities was not new. It had already appeared in August 1941 when Kodeis considered using prisoners on the Sørlandsbanen. At the time, NSB had opposed the plans, and the matter was not pursued further. However, the Polar Railway brought the question back with renewed force. Hitler had personally advocated the use of prisoners, and the question that NSB was required to investigate was whether prisoners could be used on the stretch between Mo i Rana and Fauske. The case ended up on the desk of chief engineer Bjarne Vik, who gave his assessments in the note he sent to Kodeis on 11 January 1942. Here Vik wrote that it would be possible to put between 1,200 and 4,000 prisoners on certain parts of the stretch. But as he also emphasized, this was unnecessary if a sufficient number of Norwegian workers were mobilized instead. Vik's note was also part of the larger investigation which was NSB's official reply to Kodeis after the aforementioned crisis meeting. Here, however, the main message was that NSB preferred to work with its own, free workers.

There is little indication that NSB at this time was eager to put prisoners of war to work on the Nordlandsbanen, as one easily gets the impression when reading Bjørn Westlie's book Prisoners who disappeared. According to Westlie, Vik's note should be understood as an expression that NSB was in fact in favor of using prisoner labor on the Nordlandsbanen. Westlie even writes that Vik with his note "made a fateful decision which led to thousands of prisoners becoming slave labourers. In practice, Vik and NSB here gave their support to Hitler's Germany's most violent sides." This is misleading in several ways. Westlie, firstly, underlines that Vik's report was written in response to the question of whether the section in question was suitable for the use of prisoners. Vik thus answered a "technical" question which was still of a hypothetical nature, and it was obviously not a decision on behalf of NSB. As little as the chief engineer had the authority to commit his company in this matter, the reference to the possibility of interning prisoners was an expression of the NSB management's attitude. There is little indication that NSB had changed its original objections to using prisoners. As we shall see, NSB continued throughout the rest of the war to argue for a model which meant that prisoners should not be used on the Nordlandsbanen.

In retrospect, everyone can agree that it would have turned out significantly better if Bjarne Vik and NSB had taken the opportunity to protest against all plans to put prisoners of war on railway facilities in Norway. Seen from Norwegian eyes, it is therefore a consolation that the note had little effect. In fact, there is hardly any connection between Vik's investigation and the later efforts of prisoners of war on the Nordlandsbanen under the auspices of OT. When it came down to it, it mattered little what Norwegian railway people thought about this matter. In any case, the decision rested with the Leader in Berlin.

Nordlandsmuseet, photograph: unknown

Transport problems and labor shortages

When Willi Henne arrived in Norway in March 1942, the idea was always that the Polar Railway should be built in stages, in line with Terboven's proposal. The Wehrmacht and NSB were to complete the section up to Fauske, OT was responsible for the line as a whole. The planning work started immediately. To assist in the geological mapping of the 1,200 kilometer long track, a number of German and Austrian experts came to Norway in the spring of 1942. At the same time, Henne began work on mobilizing the German construction industry.

In line with OT's model for work execution, private construction companies were to carry out most of the construction. At the end of May, representatives of a total of eight German companies, including director Baumann of Grün & Bilfinger, visited Norway to form an opinion of the railway project. After returning home, Baumann summarized his impressions in a report which in no way understated the project's challenges. But the fact that the risk was great did not rule out that there was money to be made from smaller sub-contracts. The management of Grün & Bilfinger decided to sign a contract with OT. Possibly the firm also experienced an element of coercion. As the report stated, the project was the result of a Führer's order, and it was perhaps inadvisable for a private firm to "refrain from contributing" if it wanted to avoid problems.

Photo: Norwegian Railway Museum, photographer: unknown

To organize its construction projects, Einsatzgruppe Wiking needed an extensive administrative apparatus. For the Polar Railway, four so-called superstructure managements were established in Fauske, Narvik, Nordreisa and Skipagurra in Tana respectively. In Kirkenes, there was such a unit from before. The superstructure management had a particular responsibility for bringing in supplies to the local construction sites. Because the project was dependent on trucks, machinery and other heavy equipment, a minimum of infrastructure was required. Before OT could lay a single rail, roads and quay facilities had to be put in place.

Henne had stayed in Norway for just under three weeks before he was called to Berlin on 19 April 1942. In his meeting with Hitler, the task leader made no secret of the challenges the railway project faced, including how difficult it was to secure ship space for the supplies from Germany. It made little impression. "The Führer categorically demands railway construction", the minutes from the meeting state. The track was to be built, and it was to take place within two years. A certain understanding nevertheless met Herne. Immediately after the meeting, Hitler created a new position which was given the responsibility of organizing sea transport for OT's construction projects in Norway.

Photo: RAFA3309/U67b, photographer: unknown

Initially, Her main responsibility was the section north of Fauske. At the meeting in Berlin, however, the Leader had become agitated over the lack of progress of the Wehrmacht and NSB. Delays that were initially Falkenhorst's responsibility could easily become OT's problem. Over the summer, disturbing messages came in from Kodeis. Of the 12,000 men who should have worked on the stretch between Mo and Fauske, it had only succeeded in mobilizing approx. 1,200, most civilian Norwegian workers. More labor was needed immediately. As Henne saw it, this essentially had to become prisoners of war.

In order to carry out OT's projects in Norway, Henne had initially received promises that 15–20,000 Soviet prisoners of war would be transferred from Germany. In the summer of 1942, none of these prisoners had yet arrived. Lack of manpower therefore became a central topic when Hitler gathered his advisers to discuss the Viking program on 12 August 1942. He met with Speer, Terboven and the head of the Wehrmacht's high command, Wilhelm Keitel, among others. Knowing that he had set an optimistic deadline for the completion of the Polar Railway, Terboven now took a more cautious line. Perhaps the ambitions should be adjusted down? Hitler, for his part, maintained that the aim was to build a more or less continuous line all the way to Kirkenes. As an immediate measure, he would now send 6,000 prisoners of war to Norway, earmarked for the section Mo–Fauske.

The National Archives, RAFA3309_U68, photographer: Pieper

Hitler's promise of prisoners of war was good news for Kodeis, but it also created acute challenges. At this time Kodeis could barely accommodate a single prisoner. None of the planned prison camps along the line had been completed. With, among other things, Norwegian construction companies as suppliers, the construction of the camps started in full at the end of August. However, the difficult supply situation meant that only a few of them were ready at the time the prisoners were supposed to appear. Fortunately, the prisoner transports were also delayed. Instead, the camps were filled with civilian workers, some were employed by NSB, but many were Norwegian forced labourers.

When the year 1942 ebbed, few believed that the Wehrmacht and NSB would reach Fauske within the deadline. Falkenhorst's failure paved the way for Willi Henne.

The National Archives, RAFA3309_U68, photographer: Pieper

Railway construction in the shadow of defeat

Germany's pressured military position made it increasingly difficult to supply the construction projects in Norway. In the days after the capitulation in Stalingrad, 6 February 1943, Hitler reluctantly accepted that the northernmost part of the Polar Railway, the section between Narvik and Kirkenes, was postponed until further notice. However, construction was to continue unabated on the stretch up to Narvik. More prisoners of war and forced laborers were to be sent to the Polar Railway, the Leader promised. While Einsatzgruppe Wiking had previously tried to mobilize Jewish workers from Germany without success, Hitler now allowed Jews to be employed on Norwegian railway facilities. However, no Jews were transferred to Norway as labor, their fate was different.

Because it was no longer relevant to build the northernmost part, there was also no reason to maintain the construction management in Nordreisa and Skipagurra. On 22 February, Willi Henne ordered liquidation. The resources were to be moved south and deployed on the stretch Mo i Rana–Narvik. The project had become easier, but by no means simple. It would be particularly difficult to build in the terrain around Narvik. An estimate prepared by Kodeis estimated that it could take up to nine years to complete the section between Fauske and Narvik! The construction time depended, among other things, on which route was chosen. Before the war, NSB had planned to approach Narvik via a route along the coast to Korsnes in Tysfjord, and from there complete the connection by ferry. For the Germans, this so-called coastline was far from ideal, because it was vulnerable to attack. The Wehrmacht preferred an alternative mountain line that went directly to Bjørnfjell station, not far from the Swedish border. At Bjørnfjell, the mountain line crossed the Ofotbanen, built before the war to bring Kiruna ore to ports in Narvik. Despite the fact that it would consist of long tunnels and very steep sections, this was the fastest way to secure the connection to Narvik. Willi Henne was of a different opinion. The special machines for building tunnels were almost impossible to drive up at this time, the terrain was also so rough that it was hardly possible to bring in supplies. It was Hitler who got the last word. He fell down on Her side. On 9 April, the task leader informed his staff that the Polar Railway was to follow the coastline towards Narvik.

The clarification coincided with another important event. In the first week of April 1943, Kodeis resigned as builder of the Mo–Fauske section, handing over responsibility to Einsatzgruppe Wiking.

The National Archives, RAFA3309_U68, photographer: Pieper

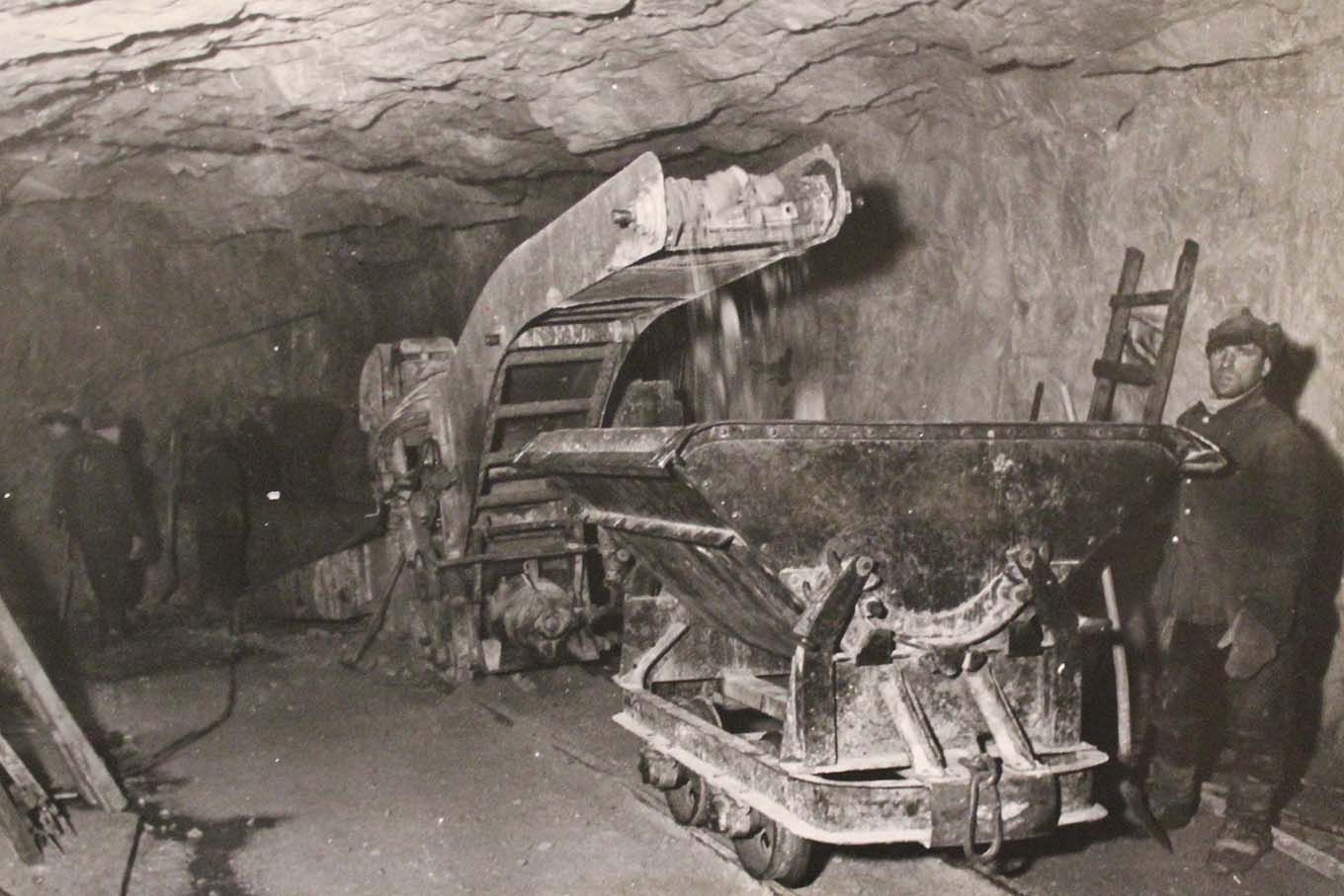

The OT model: German construction companies and prisoners of war

Kodeis had long been on the retreating front in the north, but was allowed to keep his project in the south. In other words, Falkenhorst was still the builder for Sørlandsbanen. For NSB, this meant that the company now had to serve two masters: the Wehrmacht in the south, the OT in the north. Seen from Norwegian eyes, the collaboration with the Wehrmacht had one major advantage: Falkenhorst let NSB build without interference from others.

This was not the case in the north. The Polar Railway was divided into two main sections: On the Fauske–Korsnes section, the northern section, OT built under its own auspices. Here, exclusively German construction companies were engaged. On the southern section, the stretch Mo–Fauske, NSB was still to be the main contractor. Here, since early 1942, the state company had worked closely with the Norwegian construction companies F. Selmer, Entreprenør, Eeg-Henriksen and Didrik Lund. In order to increase the pace, Henne decided that German companies should also be deployed on this stretch. NSB remained the most important contractor, but had to work closely with a total of 11 German companies, including Siemer und Müller, Funke, Röllinger and Sackmann.

Hans Renner, OT's construction manager in Mo, launched a frontal attack on his Norwegian collaborator when he met Waldemar Hoff and Otto Aubert in early May 1943. Renner was dissatisfied with the progress on NSB's part, and accused the Norwegians of coaching the project. By taking a "ten-year perspective" on everything that had to be done, NSB had deliberately undermined the deadline that "The Führer had set". At the same time, Hoff and Aubert were presented with a new administrative arrangement that ensured German supremacy at the facilities.

In the early phase, the workforce on Nordlandsbanen had consisted of free Norwegian workers who were either employed by NSB or in Norwegian construction companies. After the occupying power resorted to increasingly extensive forced deportations, Norwegian forced laborers were also sent north. Development accelerated from the autumn of 1942. Nevertheless, it was the OT's mobilization of private German firms in the spring of 1943 that made the massive effort of prisoners of war possible. It was the companies that made use of the prisoners' labour. OT's own staff was small, and employees from the companies were needed to handle the prisoners on the construction sites. They instructed the prisoners, supervised their work and were occasionally also used for simpler guard duties.

NTM, photographer: unknown

The prisoners began to flow to the facilities on the Polar Railway in April 1943, and the influx continued throughout the next year until the number approached 25,000. The vast majority came from the Soviet Union. The prisoners were kept confined in 56 prison camps that were built along the roughly 300 kilometer stretch between Mo and Korsnes. NSB had little to do with the development. The prisoners were, for example, placed elsewhere, and in far greater numbers than the note to Bjarne Vik suggested. As a general rule, the prisoners were not handed over to Norwegian actors; neither NSB nor Norwegian construction companies initially had access to the prisoner workforce. The impression created in Westlie's book, that the prisoners were "NSB's slaves" who more or less directly worked for NSB, is therefore misleading. It makes more sense to claim that the prisoners were the slaves of the OT, who in turn put them at the disposal of German construction companies. For the companies, the forced laborers were a prerequisite for being able to carry out the project at all.

National Archives, RAFA3309_U67b photographer: Pieper

NSB was fully aware of what happened in the Polar Railway's facilities and camps. At times even the company's personnel carried out similar control tasks that the employees of German construction companies contributed with. There is little indication that NSB ever confronted its German partner with the abuses witnessed by Norwegian railway workers. The closest NSB came to a protest was pointing out that OT's way of working led to a dramatic increase in construction costs. It happened in the summer of 1943 when Aubert took up the matter with the national commissariat, possibly also with Herne directly.

Aubert attacked the very core of the OT model and claimed that German firms with limited local knowledge and thousands of prisoners of war did not increase the pace of development at all. Among other things, there were too many workers for the operation to be organized effectively. According to Aubert, NSB could build as quickly as OT - at a quarter of the price. Henne was not responsive to these arguments, which in his eyes required an unacceptable "system change". The Rikskommissariat's financial experts, on the other hand, listened with keen ears. Among them was Hans Claussen Korff, who had long feared that German spending in Norway would get out of control. Fully convinced that Aubert's description was correct, he reported to the Ministry of Finance in Berlin that OT "led to delays and massive cost increases".

In retrospect, Aubert's intervention may appear naive, but it is worth noting that the solution he proposed would have contributed to the disappearance of the prisoners from the Polar Railway.

National Archives, RAFA3309_U67b photographer: Pieper

Boundless loyalty?

Fritz Todt had marked his opposition to Hitler's railway project, and there is little doubt that his successor also shared his scepticism. However, Speer refrained from direct confrontations with the Leader. If you were looking for a clearer criticism of the project, you should turn to Falkenhorst. From a military point of view, the Polar Railway made limited sense. Before it was completed, it filled neither tactical nor operational needs, and while construction was underway, it stole resources from other, more pressing tasks. In March 1943, Falkenhorst stated that the track could only be realized in the longer term, and advocated limiting the allocation of prisoners of war to the project. Hitler stirred violently when this came to his ears. The railway in the north was an urgent matter, and Falkenhorst was not to be added to the priorities in Norway. That should be left to OT.

It is hardly a coincidence that a few months later, at the beginning of September, Hitler issued a decree clarifying the OT's independent position vis-à-vis the Wehrmacht. OT was responsible for "war-important construction projects of all kinds", it said, the organization was headed by Speer - "and Speer is responsible exclusively to me". Speer was Hitler's man, and through the OT leader the Leader secured a hold on projects he attached particular importance to.

In Norway, however, the contradictions between the OT and the Wehrmacht continued to develop. In the autumn of 1943, Henne wanted resources from Sørlandsbanen, skilled workers among other things, to be transferred to OT's railway facilities in the north. Falkenhorst did what he could to undermine the decision. The Sørlandsbanen served operational needs, delays here could not be accepted - "if anything the work had to be accelerated", was the message from the Wehrmacht. The following year, in March 1944, the conflict took another turn after Hitler issued a new order dealing exclusively with the Polar Railway. The so-called Wiking II order established the track's great importance and promised OT reinforcements in the form of 4,000 German skilled workers and 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war. The Wehrmacht was to ensure that the order was carried out by, among other things, being responsible for the embarkation of the prisoners. However, Falkenhorst made it clear that the transport of prisoners could not be carried out if it blocked supplies for tasks of greater military importance. In this situation, Henne turned to Speer and asked that Hitler issue an order clarifying the military importance of the Polar Railway. Although Soviet prisoners flocked to the railway facilities throughout the summer and autumn, Henne was still dissatisfied. In November, Hitler intervened once again. As his empire crumbled around him, the Leader announced that the Polar Railway remained the highest priority and that the Wehrmacht had to ensure that the necessary ship space was made available to the OT.

The National Archives, RAFA3309_U68, photographer: Pieper

In mid-December 1944, the Wehrmacht commander in Norway was called back to Germany and dismissed from service. Falkenhorst was replaced by a general who was supposedly more loyal to the Leader and his cause. Despite the fact that Speer, for reasons of power politics, stood behind Herne in the tug of war with the Wehrmacht, he undoubtedly agreed that it was Falkenhorst who was right. The polar railway had no military significance. It was a drain on resources and an ever-increasing burden on the war economy. In a letter to Henne in November 1944, Speer admitted this at length. He would like to see, he wrote, that the railway project was scaled back. But since Hitler had once again given his support to the project, he himself could do nothing but order "full continuation". Speer washed his hands, but at the same time tried to encourage Her. The completion of the line to Narvik "was a technical honor of the highest order", he wrote. No one should ever be able to accuse us of "failing to throw ourselves into the task with the necessary energy or the joy that great technical deeds give".

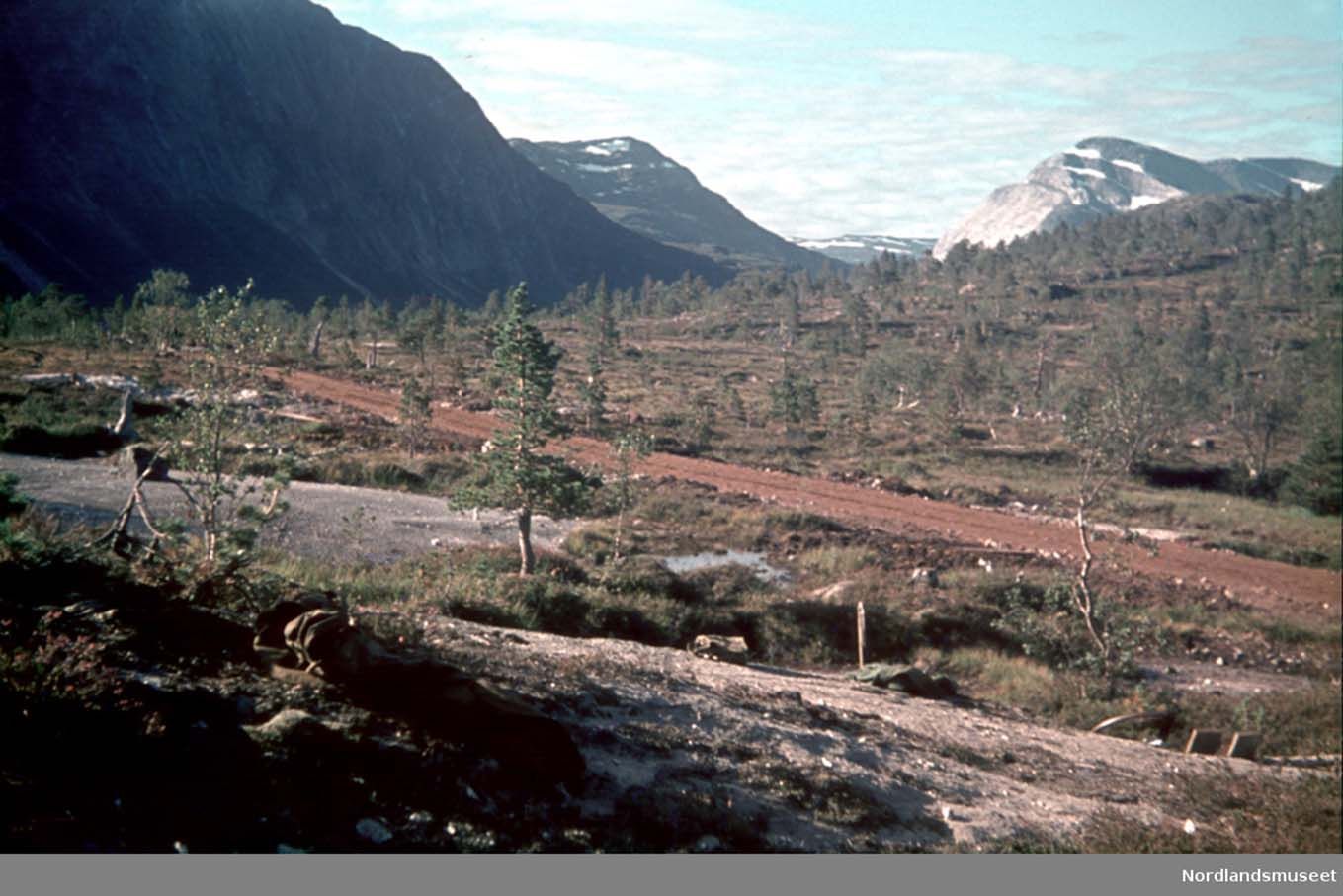

While Speer and Henne struggled with their technical honor, the prisoners suffered in the camps along the Polar Railway. In March 1945, OT's construction management in Mo i Rana announced that no more than a third of the prisoners were able to work. In the camps at Sørfjord and Buvik in Tysfjord the situation was particularly bad. There were almost no able-bodied prisoners here. No wonder, then, that the report reported slower progress and falling productivity.81 Nevertheless, construction continued right up to the last days of the war. Around 2,200 prisoners had died by then.

Riksarkivet, RAFA3309/U47, photographer: unknown

Conclusion: "Peace project in wartime"

The polar railway was a failure in the large format. Exactly how much was invested in the track is among the questions that need to be investigated in more detail. The calculations made by OT personnel immediately after the end of the war still provide some evidence. Here it is estimated that OT allocated a total of NOK 1.8 billion in resources to its projects in Norway and that the Polar Railway accounted for NOK 164 million of this. However, this estimate is certainly too low, as costs related to the use of prisoners of war are not included. The same probably also applies to the transport costs and at least parts of the building materials that were included. In addition, we know that a good part of the resources that were invested in the section Mo–Fauske were channeled through NSB's budgets. All in all, this means that the total expenditure for the Polar Railway is most likely somewhere between NOK 200 and 250 million.

Seen in the light of the original plans and the resources put in, the results were rather modest. Of Hitler's 1,200 kilometer railway line, only 137 kilometers were completed. It was on the stretch between Mo i Rana and Fauske, today's Nordlandsbane, that the work came the furthest. The line was still nowhere near passable all the way to Fauske. Further north, on the stretch between Fauske and Korsnes, the "degree of completion" was a modest two percent, according to Willi Henne himself. When Henne was asked after the war to reflect on the Polar Railway's rationale, he had trouble finding one. The skilled engineer could not explain why a project which in every way appeared to be a long-term "peace project" had been started "in the middle of a brutal war". The Germans' fondness for Norwegians "wasn't that great after all".

The National Archives, RAFA3309_U67, photographer: Pieper

Both Henne and Speer knew that the path seized resources that could have been used more sensibly elsewhere, but shied away from confrontations with Hitler. In their eagerness to live up to the Leader's wishes and expectations, they contributed to creating a system that increasingly undermined the ability to make rational decisions. In this sense, the Polar Railway is an instructive example of the perversion of economic coordination and resource use that developed in the Førerstate. The decision to build a railway to Kirkenes in two years was taken beyond all practical economic sense. Instead, the track can be seen as an expression of Hitler's voluntarist view of technology, the notion that scarce time and limited resources represented no obstacle as long as the Leader insisted that the project be carried out. That the path strictly did not make sense in the short term, Hitler chose to ignore. Instead, he allowed himself to be seduced by the track's potential in the long perspective, its importance for the new order of Europe, the future Grossraum. The fact that Hitler wanted OT as a builder was hardly accidental. OT had on a number of occasions demonstrated the results that could be achieved with the help of technology and efficient organisation. There is therefore considerable irony in this that the man who had given the organization its name, Fritz Todt, was the one who most clearly saw the project for what it was - pure wishful thinking.

The construction of the Polar Railway constitutes a dramatic chapter in NSB's history, a chapter that has not yet been written. Although NSB can hardly be said to have had any active role in the decision to put prisoners of war to work, the company was not a passive party in the realization of German railway plans. Somewhere along the way, the cooperation with the occupying power was considered to be justifiable because it opened the way for the realization of Norwegian pre-war plans. While the strategy worked reasonably well against the Wehrmacht, the Norwegians lost most of their control when the OT appeared. Through the collaboration with OT, employees of the company became eyewitnesses to war crimes on Norwegian soil. The cautious attempts to oppose the OT model led to little other than NSB itself being incorporated into the system.

The National Archives, RAFA3309_U67, photographer: Pieper

Notes

- Walther Hubatsch, Hitler's Weisungen für die Kriegsführung 1939–1945, Koblenz 1965: 170–172.

- The name Polarjernbanen rarely appears in the sources, nor is it used consistently. Kirkenesbanen or Finnmarksbanen are often used instead. In the research literature, the Polar Railway is still the most incorporated term. All translations are made by the author.

- Alan Milward, The Fascist Economy in Norway, Oxford 1972: 272.

- Xaver Dorsch, Die Organization Todt, in Hedwig Singer (ed.), Quellen zur Geschichte der Organization Todt, vols 1–2, Osnabrück 1998: 496.

- Adam Tooze, The Wages of Destruction. The making and breaking of the Nazi economy, London 2006: 139; Ketil G. Andersen, Technological and economic reason. Doctoral thesis UiO, Oslo 2002: 309–311.

- About the establishment of Einsatzgruppe Wiking, see the contributions to Sæveraas and Frøland in this booklet.

- Milward 1976: 274–278; Robert Bohn, Reichskommissariat Norwegen, Munich 2000: 363–370; Marianne Neerland Soleim, Soviet prisoners of war in Norway 1941–1945. Number, organization and repatriation, Oslo 2009: 126–134; Berit Nøkleby, Hitler's Norway, Oslo 2016: 269–271.

- Joachim Petersen, Hitler's Polarisenbahnpläne 1940 bis 1945 in Nordnorwegen, Ronnenberg 1992.

- Bjørn Westlie, Prisoners who disappeared, Oslo 2015; Silje Thjømøe, War collaborators or railway engineers? Master's thesis in history, NTNU 2013; Finn Rønnebu, An adventure of shame, Sandnes 2017.

- Jon Gullowsen and Helge Ryggvik, New times and old tracks 1940–2004, vol. 2 in Gullowsen and Ryggvik, Jernbanen i Norge 1854–2004, Bergen 2004: 31.

- Arvid Ellingsve, Nordlandsbanen's war history, own print, 1988: 13; Westlie 2015: 52; Thjømøe 2013: 1.

- Bohn 2000: 364; Ellingsve 1988: 5–7.

- Hans Clausen Korff, Norwegens Wirtschaft in Mahlstrom der Okkupation, undated manuscript, probably 1947: 220–223, 231–232; Milward 1972: 119–120; Bohn 2000: 364. See also the contribution to Frøland in this booklet.

- Gullowsen and Ryggvik 2004: 38–39.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, letter, Neyer to the Ministry of Labour, Nordlandbahn Mo–Fauske–Bodø, 16.1.1942, note, Aufnahme – Niederschrift, 15.4.1942, and minutes, Besprechung vom 6.1.1942 mit Herrn Ing. Kolsrud, 6.1.1942.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, report, Baubesprechung bei der NSB Zentrale Oslo, 29.1.1941.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, letter, probably from NSB or the Ministry of Labor to the Reichskommissariat, Nordlandbahn Mo–Bodø, 12.11.1941.

- Gunnar Hatlehol, "Norwegeneinsatz" 1940–1945. Organization Todt's workers in Norway and the degrees of coercion. Doctoral thesis NTNU 2015: 203–205.

- Hubatsch 1965: 170–172.

- BA-MA, RH 20-20/203, memorandum, Todt, Nachschub und Verbindungssicherung Nordnorwegen–Finland, 9.10.1941.

- See same.

- NHM, F/II box 20: Bericht und Vernehmung des Generalobersten von Falkenhorst, Oslo, Sept./Oct. 1945, p. 43. (Hereafter: Falkenhorst's report 1945.)

- Petersen 1992: 77.

- Adolf Hitler, Monolog im Führerhauptquartier 1941–1944. Die Aufzechnungen Heinrich Heims herausgegeben von Werner Jochmann, Hamburg 1980: 90–92.

- Franz W. Seidler, Fritz Todt – Vom Autobahnbauer zum Reichsminister, in Ronald Smelser and Rainer Zitelmann (eds.), Die Braune Elite. 22 biographical sketches, Darmstadt 1990: 308; Tooze 2006: 507.

- Franz W. Seidler, Fritz Todt. Baumeister des Dritten Reiches, Munich, Berlin, 2000: 356; Tooze 2006: 507.

- RA RAFA 2174, E/Ef/L0003, Klein, various notes, see especially Strassen und Eisenbahnen, 3.12.1941 and Strassenbau, 1.12.1941.

- Falkenhorst's account 1945: 43–44, Milward 1972: 274.

- RA RAFA 2174, E/Ef/L0003, Klein, Strassen und Eisenbahnen, 3.12.1941 and Strassenbau, 1.12.1941.

- RA/RAFA 2174, E/Eb/Ebd/L0053, note, Klein, Bahn- und Strassenbau in Nord-Norwegen 19.1.1942, RA/RAFA2174, E/Ef/L0003, note, Hermann, Einsatz russischer Kriegsgefangener. Ausbau von 2 Durchgangslagern in Tromsø und Alta, 6.2.1942, letter, Klein, Inspekteure für die Landesbefestigung, 10.2.1942.

- Hatlehol 2015: 207.

- RA RAFA 2174, E/Ef/L0025, Klein, memo, 17.1.1942.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT1, E2b-L0006, Neyer, notice, Strassen- und Bahnbau in Nordnorwegen. Contingente für Eisen- und Nichteisenmetalle, 13.2.1942.

- Tooze 2006: 509 and Seidler 1990: 311.

- Falkenhorst's report 1945: 44.

- BA-B R3/1503, Besprechung Speer–Hitler am 19.2.1942.

- Conf. Hatlehol 2015: 85–89.

- Martin Moll (ed.), Führer-Erlasse 1939–1945, Stuttgart 1977: 249.

- Willi Henne, Die Organization Todt in Norwegen, (unpublished manuscript in three parts) 1945, part 1: 9, OT archive, IHS, NTNU; RA RAFA, 2188, OT1, E2k-L0078; note, Her, Besprechung, 18.8.1942.

- Falkenhorst's report 1945: 44.

- Conf. Moll 1977: 249.

- RA/RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, report, Baubesprechung bei der NSB Zentrale Oslo, 29.1.1941.

- RA/RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, Notat, Arnoldy, Besprechung von 5.2.1942, 5.2.1942, note, Henke, Aktennotiz über die Besprechung am 12.1.42 mit der Fa. Contractor, 13.1.1942.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, report, Baubesprechung bei der NSB Zentrale Oslo, 29.1.1941.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, NSB to Kodeis, Bahnbau Mo–Fauske, 20.1.1942, p. 12.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, letter, Falkenhorst to NSB, 16.1.1942.

- SA NSB/Ellingsve-samlingen/20, letter, Aubert, Railway construction workers, 11.8.1941; Westlie 2015: 72.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, Note, Bjarne Vik, Forcierter Bau der Strecke Mo–Fauske, 11.1.1942.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001: NSB to Kodeis, Bahnbau Mo–Fauske, 20.1.1942, p. 6.

- Westlie 2015: 86.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, Note, Bahnbau, 30.4.1942, and Henne 1945, part 1: 10.

- Unternehmensarchiv der Bilfinger SE, Mannheim, A 2797, Bericht über die Streckenbesichtigung des Bauvorhabens Eisenbahn: Fauske–Narvik–Kirkenes, 15.6.1942, p. 3.

- Hatlehol 2015: 86.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT1, E3c-L0007, Letter, Ferkov to Schwanke, Arbeitsbedarf für Bahnbau, 24.6.1942; Her 1945, part 1: 17–18.

- BA-B, R3/1503, Besprechung Hitler-Henne-Dorsch-Jacob-ua am 19.4.1941; Willi A. Boelcke, Deutschlands Rüstung im Zweiten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt am Main 1969: 105, 140–141.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, note, Arnoldy, Betr.: Neubau-Bahnstrecke Storfosshei–Fauske, 7.8.1942.

- BA-B, R3901/20215: letter, Koester to the Ministry of Labour, Arbeitseinsatz; hier Verpflichtung von Arbeitern für Norwegen, 11.3.1942.

- BA-B R3/1505, Besprechung am 10/11/12.8.1942.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0001, minutes, Dörr and Arnoldy, Neubau der Strecke (Mo–) Storfosshei–Fauske, 6. 8.1942; memo, Arnoldy, Eisenbahnkommando Norwegen, 2.9.1942.

- Boelcke 1969: 233–234.

- RA RAFA, OT1, E3c-L0007, Her, Betr.: Organisation, 22.2.1943.

- Petersen 1992: 128.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT1, E3c-L0007, Note, Bahnbauprogramm und Umdispositionen auf der Strecke Mo–Korsnes, 19.4.1943; Boelcke 1969: 244; Her 1945, Part 1: 13.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT1, E3c-L0007, note, Schwartz, Über die Bereisung der Bahnbauoberleitungen Mo–Fauske und Narvik II, 31.10.1943.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT2, Hg-L0003, note, Renner Vorschlag über die Zusammenarbeit zwischen OBL und der NSB bezw. Zwischen OBL und norw. Wegwesen, 2.5.1943; note Vermerk über eine Besprechung zwischen NSB und OT, undated, probably mid-May 1943.

- Rønnebu 2017: 90. Michael Stokke, Narvik Centre, operates with higher figures: 26,000 prisoners and 58 prison camps.

- Westlie 2015: 135.

- Conf. Google's article in this booklet.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT1, E2b-L0015, note, Renner, Vermerk, 9.2.1944.

- BA-T, R2/30513, Korff, Aktenvermerk, 21/9/1943; letter, Korff to Breyhan Bahnbau in Norwegen 31.8.1943, and memo, Breyhan, Bahnbauten in Norwegen, 23.9.1943.

- BA-T, R2/30513, Korff to Breyhan, Bahnbau in Norwegen, 31.8.1943.

- Boelcke 1969: 257.

- Erlass des Führers über die Organization Todt, 2.9.1943, Singer 1998: 161.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT1, E3c-L0007, letter, Falkenhorst/Bamler to GB Bau (Henne/Feuchtinger), Abgabe von Arbeitskräften der Südlandbahn, 13.12.1943.

- Moll 1977: 405.

- BA-B, R3/1593 fol. 127–130, Her to Speer, 30/5/1944.

- Boelcke 1969: 429.

- Bohn 2000: 43.

- BA-B, R3/1582 fol. 162, Speer to Her, 6 November 1944.

- See same.

- RA RAFA 2188, OT1, E3c-L0007, note, Renner, Besprechung mit Sonderstab O 14.3.1945; OT2, Hg-L0007, note, Kriegsgefangeneinsatz, 15.1.1945.

- Based on estimates made by Michael Stokke, Narviksenteret.

- NHM, FO.II/11.4, box 27, folder 56b, OT-Wiking-Abrechnungsstelle: Bauaufgaben der OT in der Zeit 1942–1945, 3.9.1945. Expenditure for the establishment of bases in Troms and Finnmark is included in the cost estimate for the Polar Railway. About OT's spending in Norway, see Frøland's contribution in this booklet.

- Gullowsen and Ryggvik 2004: 32.

- Her 1945, Part 3: 46.

- See same: 43.