Organization Todt and forced labor in Norway 1940 – 1945

Technology as propaganda

"Technology is to serve the people" (Technik ist dienst am Volk) - Slogan, Fritz Todt

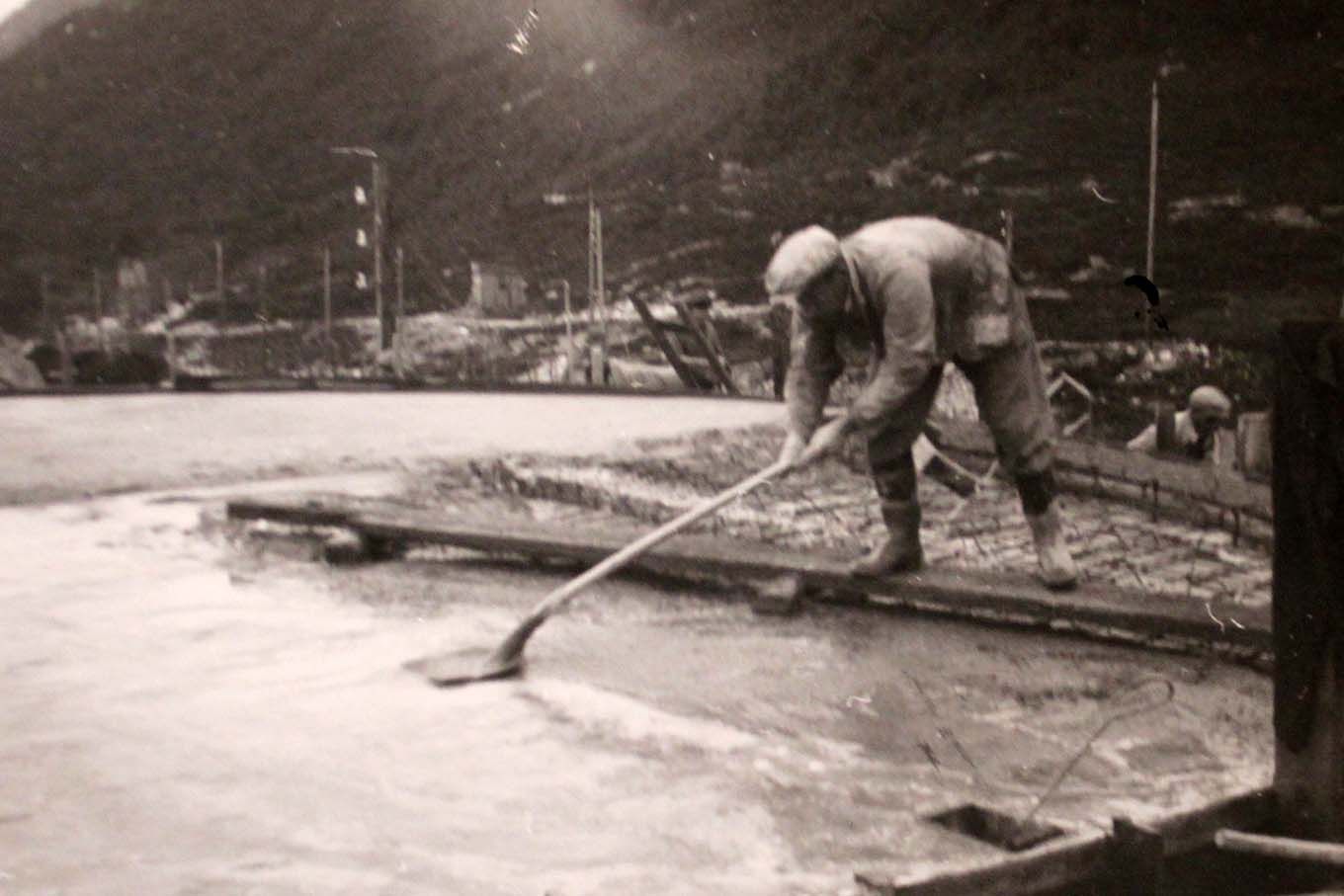

Photo: Romsdalsmuseet, photographer: unknown

Fritz Todt emerged in the years after Hitler's rise to power in 1933 as Germany's foremost engineer. Through the Nazifisation of the engineers' organisations, Todt secured a key position within the engineering profession. He advocated raising the reputation of engineers and wanted to create an elite corps of engineers who would take over key positions in social life. Many engineers supported Todt's idea of creating a separate Ministry of Engineering. As head of the Nazi party's technical office, Todt was behind the publication of the propaganda magazine Deutsche Technik.

In 1936, the medieval castle Plassenburg was turned into a course center for selected engineers who were to be given "technopolitical" training. The program included everything from physical education and racial studies to road construction and classical music. Todt claimed that under National Socialism the technique had finally found its place in German culture.

"Technology is to serve the people" (Technik ist dienst am Volk)

Slogan, Fritz Todt

In the late 1930s, with Deutsche Technik as its motto, Todt organized annual propaganda tours for engineers and party people. In the spring of 1939, the trip went to Norway.

Photo: Riksarkivet RAFA3309_52, photographer: unknown

The militarization of work: With a spade and a gun

When the Nazis came to power, 6 million Germans were out of work. At the same time as the political and professional organizations of the working class were struck down, the regime initiated public measures against unemployment, including through large road projects. From 1935, six months of compulsory work for men was organized through the public employment service Reichsarbeitsdienst. The organization was run on a military model. Discipline was strict and at mass events the workers paraded with shovels on their shoulders as if they were soldiers with weapons. This is how the labor service functioned in preparation for the war.

Organization Todt (OT) was also organized according to military models. The construction organization was established in 1938, after Fritz Todt was commissioned to build large concrete fortifications along the border with France. The West Wall, or the Siegfried Line, as the facilities were called, employed tens of thousands of workers, many of whom were forced out of work. Eventually, it became common for the OT to cooperate with the security police to maintain discipline among the workers.

The OT and Reichsarbeitsdienst were used by the Nazi regime to discipline the working class and to direct labor towards military construction projects. At the same time, these organizations helped to blur the distinction between the war and peace economy.

Photo: The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology C 12213, photographer, unknown

Car for the people?

The plans to build a car that broad sections of the population could afford to buy, a people's car, were launched by Hitler in 1934. While design and construction was left to the engineer Ferdinand Porsche, the German Labor Front welfare organization Kraft durch Freude (KdF) was to stand for production and sales. The car's official name therefore became the KdF-Wagen. After the launch of a prototype in 1936, the car was ready for mass production two years later. It was supposed to cost 1,000 reiksmark; significantly less than the competitor's models. The Labor Front was responsible for the construction of a state-of-the-art factory which was almost finished before the war broke out. A separate system for selling the car was also developed. People undertook to save part of their salary, 25 reiksmark a month, which went towards paying off the car.

Folkevogen was a sign of material progress and social mobility for the population. In the propaganda, the car was presented as the realization of the Nazi "commonwealth". The investment in civilian mass consumption nevertheless revealed itself as a bluff when it turned out that the project came into conflict with the needs of the armaments industry. In 1940, the new factories in Fallersleben were converted to the production of military equipment. At this time, only 751 civilian passenger cars were produced.

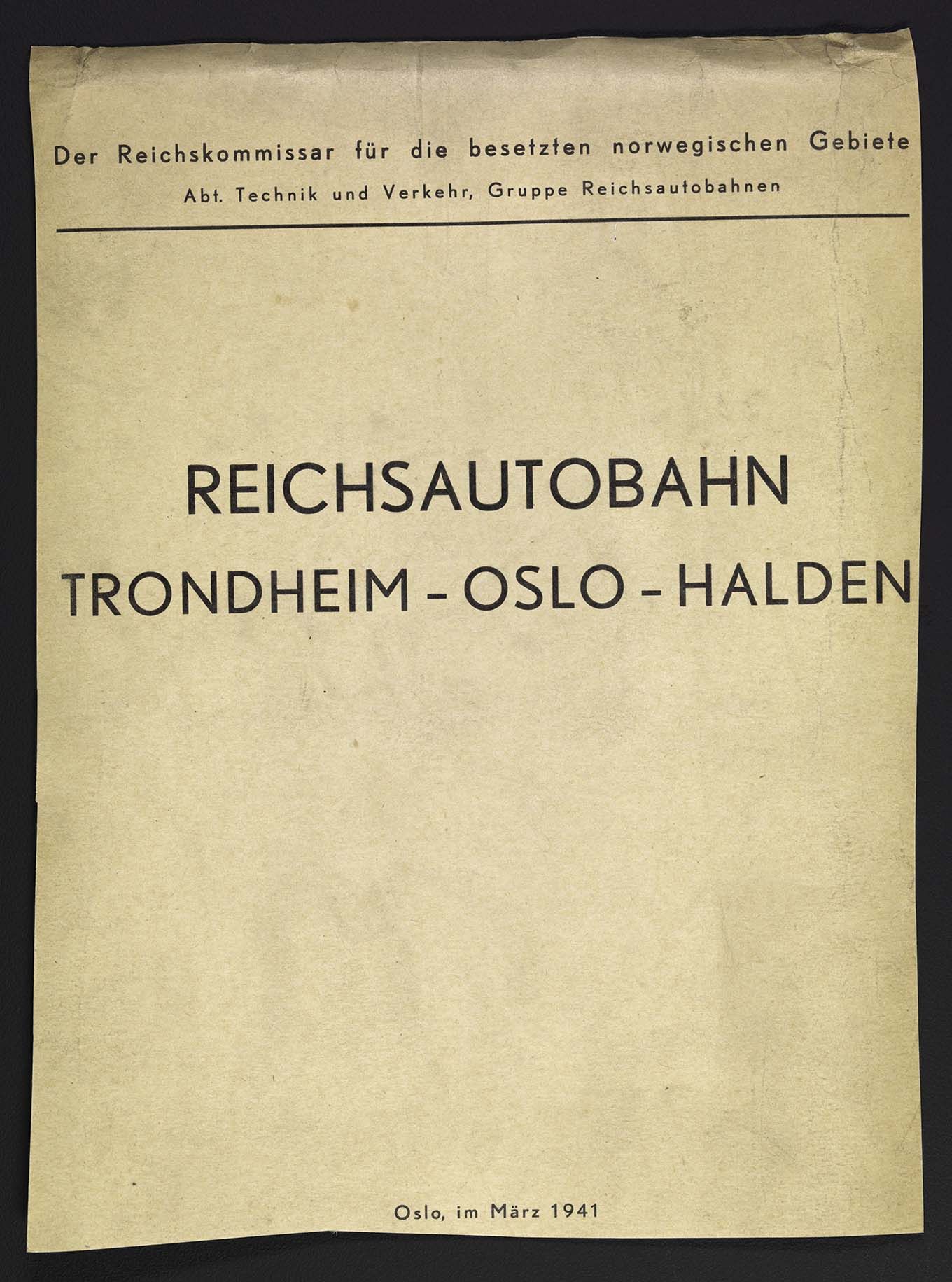

The National Archives, RAFA 2188

The Driver's Roads: Die Reichsautobahn

When Fritz Todt was appointed road director in 1933, there were already motorway plans in Germany. The Nazi regime expanded the plans and made them their own. The goal was to build 7,000 kilometers of road within eight years. The roads were to maintain a high standard and be financed from public budgets. In the first years, the unemployed, housed in primitive camps, were used for the work. As labor became scarce, coercive methods were used to ensure recruitment. Todt was given wide powers and reported directly to Hitler.

A separate philosophy was developed around the road projects. The routes that were set out were not necessarily the shortest measured in kilometers. It was more important that the roads blended harmoniously into the landscape, so that motorists could experience the beauty of nature. There was no conflict between technology and nature, Todt claimed.

As the Third Reich conquered new territories, Todt and Hitler planned an expansion of the Autobahn network. The aim was to reach the Caucasus in the east and Trondheim in the north. Between 1940 and 1943, Norwegian and German road engineers worked on the planning of the Reichsauthobahn from Halden to Trondheim on behalf of Todt.

Photo: MA students from the Academy of Performing Arts, Østfold University College, 2015.

Architecture as propaganda

The Third Reich was to be realized through large, monumental buildings. With Albert Speer at the head, the regime's architects set about planning the rebuilding of cities in Germany and the occupied territories. The architecture was also used in the political mobilization of the masses. In Nuremberg, where the Nazi Party held its annual congress, architecture's propaganda potential was effectively demonstrated. One of Speer's inventions was to surround the central meeting place with powerful floodlights. When the floodlights were lit and beamed up into the night sky, those present had the feeling of being inside a giant room held up by pillars of light - a "cathedral of light".

The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology , photographer: Håkon Bergseth

Germania

Hitler wanted to make Berlin the largest and most magnificent city in the world - "Welthauptstadt Germania". Albert Speer started the planning work in 1937. Based on sketches Hitler himself had drawn, Speer built models of the most central buildings. Among them we find the 290 meter high domed hall, Grosse Halle.

Admiring the model of Germania was among Hitler's favorite pastimes already in 1925. Although the project was canceled in 1943, when the fortunes of war turned, it nevertheless left its mark. All around Germany, concentration camp prisoners were made to cut stone under inhumane conditions. In the areas that were to be renovated to make room for Speer's magnificent buildings, tenements were emptied. Germans, who were affected by this, were allowed to move into so-called "Jewish housing". The fact that the Jews lost their homes in this way was not emphasized. The evictions were organized by Albert Speer.

Photo: The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology , photographer: Håkon Bergseth

Norwegian granite for Germania

In the summer of 1940, Albert Speer sent a delegation to Norway to investigate whether the Norwegian granite was suitable for the monumental buildings he planned in Berlin. Various samples were presented to Hitler, and he was "very excited about the colors in the Norwegian stone". Speer ordered huge quantities of stone in Norway. The entire Norwegian stone industry from Aust Agder to Østfold was involved in the enormous deliveries. Parts of the industry were reorganized under German auspices, and Norwegian stonemasons traveled to Speer in Berlin for training. Due to a lack of transport options, only a fraction of the granite ended up in Berlin.

"The driver has been presented with the rock samples from Norway and is very excited about the beautiful colors in the Norwegian granite."

Albert Speer in letter to Joseph Terboven August 1, 1940.

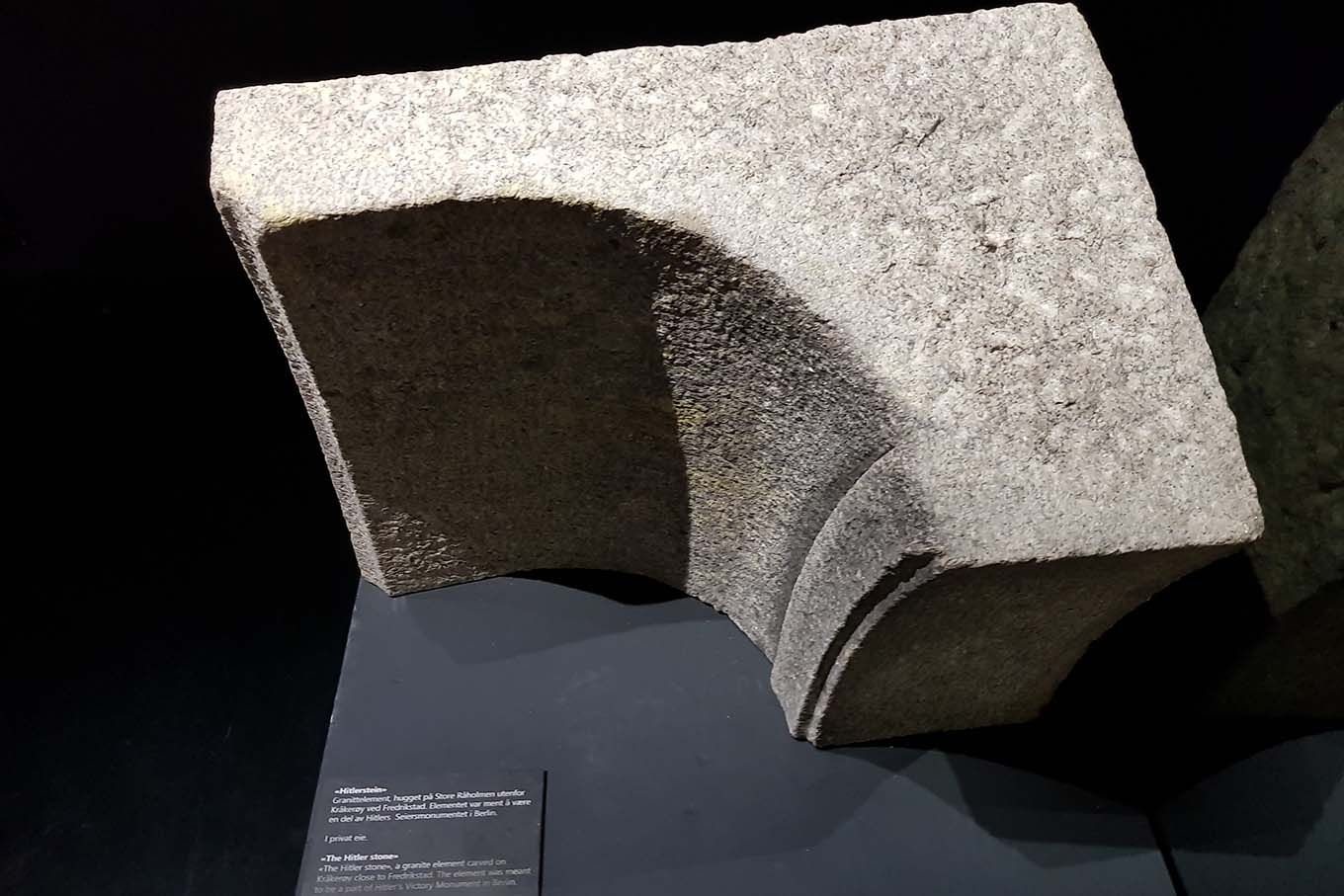

Photo: The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology , Kathrine Daniloff

Prisoners of war to Norwegian quarries?

"There are plans in Germany to commemorate Germany's current position with a series of magnificent buildings of such dimensions that the necessary quantities of natural stone cannot be obtained in sufficient quantities in Germany. [..] The program includes deliveries for 10 to 15 years. Dr. Klein insisted that enough workers should be obtained, and it was considered from the German side to send prisoners of war here to work also in the stone industry for the intended deliveries to Germany..." Minutes from a meeting between representatives of the Norwegian stone industry and Heinz Klein from the Reichskommissariat technical department, 9 July 1940.

The proposal to put prisoners of war to work in Norwegian quarries was never implemented. It turned out that the quarries were too small and too scattered for the prisoner effort to be organized in a safe and financially sound manner.

The Victory Monument – rewriting history through architecture

As part of his Germania project, Hitler planned a gigantic Victory Monument. It was to be 117 meters high, 170 meters wide and 120 meters deep. The names of all German soldiers who fell during the First World War were to be engraved. With a victorious end to the Second World War, Hitler wanted in this way to correct the shameful defeat of 1918.

Already in 1925, Hitler, who at the time led an insignificant party on the extreme right wing, had drawn a draft for the monument. On the occasion of Hitler's 50th birthday, in 1939, Albert Speer made a model of the monument based on this drawing.

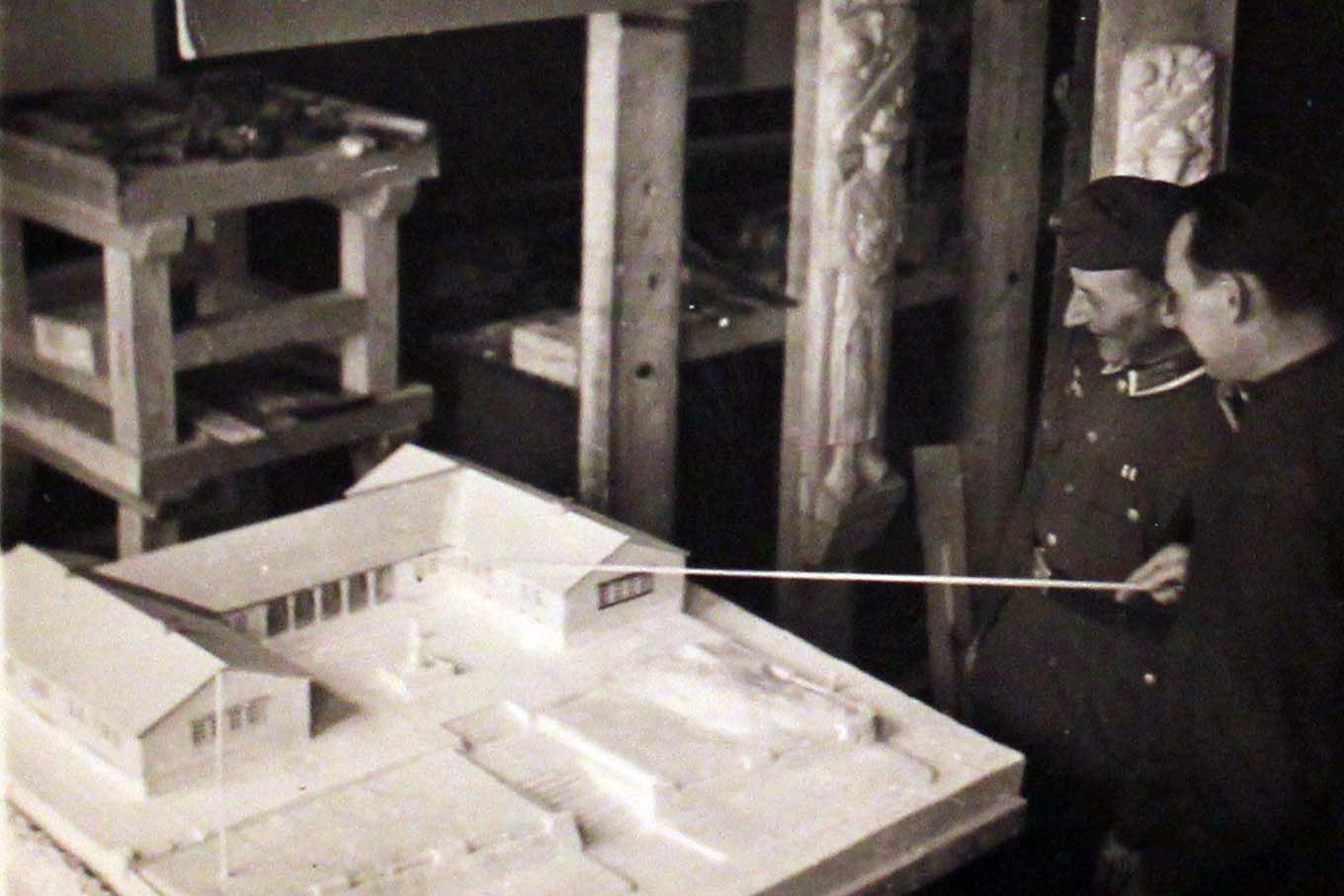

Riksarkivet, RAFA3309_U67b, photographer: unknown

Trondheim in Berlin

In the summer of 1940, the German Reichskommissariat commissioned a model of the Trondheimsfjord from Norsk Modellerings Kompani in Oslo. The actual client was Armaments Minister Fritz Todt, who acted on behalf of Hitler. The model, which covered a total of 48 square metres, was transported to Berlin and installed in the model hall in the Reich Chancellery. Todt, Speer and Hitler used it in the planning of a number of major building projects. Initially, a submarine bunker was to be built in Trondheim, later the idea was to build a naval yard and a dry dock some distance outside the city. In connection with these installations, Hitler envisioned the construction of a new city with 250,000 inhabitants - Neu Drontheim. In June 1941, he decided that the new city should be built at Gulosen southwest of Trondheim.

To carry out the foundation works in Øysand, Organization Todt used, among other things, Soviet and Yugoslav prisoners of war. Only the submarine bunker in Trondheim – Dora – was completed.